The Great American Steamboat Race (18 page)

Read The Great American Steamboat Race Online

Authors: Benton Rain Patterson

Stairway leading up from a typical steamboat’s boiler deck, the deck above its main deck, to the hurricane deck, or promenade deck. At right in this photograph is the purser’s, or clerk’s, office. Passengers reached the boiler deck by climbing gracefully curving stairways that rose from the steamer’s main deck near the bow of the boat (Library of Congress).

est, was called the main deck, which stood about four feet above the surface of the river. That was where the boat’s machinery was mounted, with the boilers positioned forward and the engines positioned between the two huge paddle wheels. Some of the boats, of course, had a single paddle wheel, mounted on the stern. Also on the main deck were the galleys, space for freight and space for deck, or steerage, passengers, whose low fares entitled them to little more than passage and a sleeping spot on a cot, a bench or on the boards of the deck itself. Ten to eighteen feet above the main deck and reachable by a pair of curving stairways near the bow, was the boiler deck, or saloon deck, on which were the passenger staterooms, the barroom, the saloon — or main cabin — and the boat’s offices. A promenade, like a porch, encircled the staterooms on the outside and could be accessed from the staterooms, from the saloon or from gangways, allowing cabin passengers to stroll or sit — on benches or chairs — and watch the passing scenery on the river and along the shore.

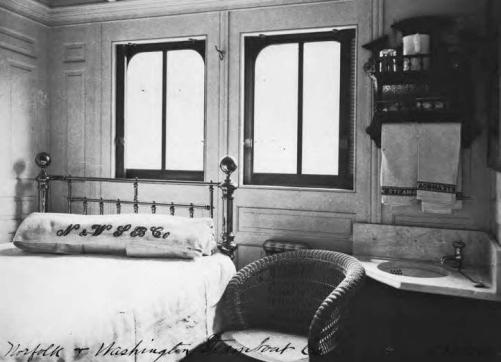

Interior of a stateroom. The grand saloon on either side was lined by staterooms with doors that opened into the saloon and also with doors that opened onto a porchlike promenade that encircled the boat’s superstructure, allowing first-class passengers to stroll or sit and watch the passing scenery on the river and along the shore (Library of Congress).

Above the boiler deck was the hurricane deck, or promenade deck, with a cluster of cabins called the texas, in which the boat’s officers were quartered. On top of the texas stood the pilothouse, or wheelhouse, some fifty feet above the water, presenting a commanding view of the river that lay before the bow of the boat. (A common belief is that the texas was so called because in the 1840s staterooms were named after the nation’s states and the cabins that were occupied by the boat’s officers, a recent addition to the steamboat’s design, were named texas for the state of Texas, which in 1845 was the nation’s newest addition. Another explanation for the name is that the officers’ staterooms were the largest on the steamboats and therefore they received the name of the then-largest state, Texas. One other popular belief is that the cabins occupied by passengers and the boats’ officers were called staterooms because they were named after states. However, the term stateroom, or state-room, had been used to mean a grand room in a palace or mansion before it was ever applied to a cabin on a steamboat or ship.)

A first-class ticket on a Mississippi River steamboat traveling upstream might cost as much as twelve and a half cents a mile, but about half that amount when the boat was headed downstream. In either case, fares were often negotiable with the captain, who in eagerness to take aboard as many paying passengers as possible would stop en route to pick them up when they hailed him from the shore, day or night.

For passengers who were unable to foot the expense of a first-class ticket, travel on a Mississippi River steamboat was considerably more austere and mean than it was for cabin passengers. Negro slaves and steerage-class white passengers, whose passage from New Orleans to St. Louis might cost as much as three dollars each, were quartered on the main deck, finding room wherever they could in between stacks of freight, forbidden to ascend to the upper decks. For sleeping, they brought their own bedding or did without. The boat provided a stove for cooking, but the deck passengers had to supply their own food, which was usually sausage, dried fish, or crackers and cheese — and a bottle of whiskey to wash down all that dry food. The deck passengers included farmers who had given up trying to wrest a living from poor soil in the eastern U.S. and were seeking more promising farmland in the West, and immigrants straight from Europe, seeking new lives in a new land, looking for a job and a place to start. Some others were simply restless individuals on the lookout for something better, something different, often bringing their wives and young children along with them on the quest. Others were peddlers, traveling with their wares from town to town, wherever the boat would stop.

Still others, particularly in the Mississippi steamboat’s early days, were flatboat or raft crewmen who had come down the river on their vessels, which had been broken up and sold as lumber at their destination, and were returning to their homes upriver aboard a steamboat. They were a raffish bunch who treated the steamboat ride as a boisterous vacation, swilling rum and singing and shouting and firing their pistols into the air throughout much of the night. The negro slaves traveling as deck passengers, some of them bought in New Orleans and on their way to new locations, some being taken to New Orleans to be sold, were, like the flatboat crewmen, also temporarily free from their usual hard work, and many of them made the most of their trip, singing and dancing and generally celebrating the time aboard the boat as if it were a holiday. Charles Dickens, the British novelist, traveled aboard a Mississippi River steamboat in 1842 and complained that the passengers on the main deck kept him awake at night with their noise, shooting guns and singing hymns.

Music was one of the big attractions of Mississippi River steamboats. A brass band or an orchestra became standard equipment on the boats. It played for passengers in concerts and for dances during the voyage and it played for townspeople when the boat docked. Perhaps even more enjoyable to passengers was the music made by the free Negroes who worked as waiters, barbers, porters and deckhands aboard the steamboats. “They played stringed instruments,” one observer commented, “and sang as only they could play and sing those haunting, joyfully sad melodies and hymns.”

7

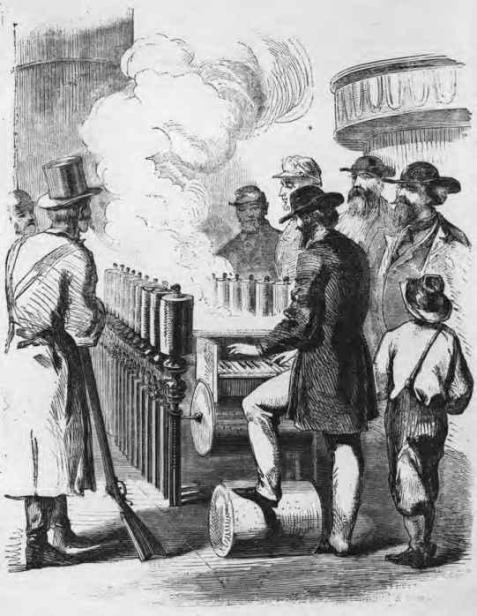

The calliope, or steam organ, or steam piano, was invented in 1855 (by Joshua C. Stoddard of Worcester, Massachusetts) and, although intended by its inventor to replace church bells, it soon found itself adopted by steamboat owners, who mounted the instruments on the exterior of the boats and had them played to charm not only the boats’ passengers but people along the shore, the distinctive, cheery sound audible many miles away from the river.

The calliope, however, received mixed reviews once passengers had experienced it while aboard a steamboat. One long-time pilot on the upper Mississippi, George Byron Merrick, although acknowledging that music was important to passengers, did not think the calliope’s tones made the sort of music that boosted the boats’ passenger business:

In the flush times on the river all sorts of inducements were offered passengers to board the several boats for the up-river voyage. First of all, perhaps, the speed of the boat was dwelt upon.... After speed came elegance —“fast and elegant steamer”— was a favorite phrase in the advertisement....

After elegance came music, and this spoke for itself. The styles affected by river steamers ranged from a calliope on the roof to a stringed orchestra in the cabin [saloon]. The “Excelsior,” Captain Ward, was the first to introduce the “steam piano” to a long-suffering passenger list. Plenty of people took passage on the “Excelsior” in order to hear the calliope perform; many of them, long before they reached St. Paul, wished they had not come aboard, particularly if they were light sleepers. The river men did not mind it much, as they were used to noises of all kinds, and when they “turned in” made a business of sleeping. It was different with most passengers, and a steam piano solo at three o’clock in the morning was a little too much music for the money. After its introduction on the “Excelsior,” several other boats armed themselves with this persuader of custom; but as none of them ever caught the same passenger the second time, the machine went out of fashion. Other boats tried brass bands; but while these attracted some custom they were expensive, and came to be dropped as unprofitable.

The cabin [saloon] orchestra was the cheapest and most enduring, as well as the most popular drawing card. A band of six or eight colored men who could play the violin, banjo, and guitar, and in addition sing well, was always a good investment.... They also played for dances in the cabin, and at landings sat on the guards and played to attract custom. It soon became advertised abroad which boats carried the best orchestras, and such lost nothing in the way of patronage.

8

After-dinner activities aboard the steamers varied widely — and simultaneously. Passengers were allowed to amuse themselves as they pleased, so long as they did not infringe on the rights of others and did not interfere with

A steamboat calliope. Music was one of the big attractions of Mississippi River steamboats, and the calliope, invented in 1855, soon became a standard feature on steamers. It was mounted on the boats’ exterior, and its distinctive, cheery sounds charmed not only the boat’s passengers but people along the shore (Library of Congress).

the crew and the workings of the boat. “There might frequently be seen in the ladies’ cabin a group of the godly praying and singing psalms,” one traveler recalled, “while in the dining-saloon, from which the tables had been removed, another party were dancing merrily to the music of a fiddle, while farther along, in the social hall, might be heard the loud laughter of jolly carousers around the drinking bar, and occasionally chiming in with the sound of the revelry, the rattling of money and checks, and the sound of voices at the card-tables.”

9

Many steamboats had a rule that prohibited gambling after 10

P

.

M

., but the rule was largely ignored, and it was not unusual for card games to last through the night and into the dawn of a new day. Some boats posted signs warning that gentlemen who played cards for money did so at their own risk. In the convivial atmosphere that prevailed after dinner in the saloon, members of the crew —“uncouth pilots, mates, and greasy engineers”

10

—sometimes joined well-dressed passengers at the card tables. The most common card games were poker, brag (similar to poker), whist, Boston (which required two decks of cards), and old sledge (also called seven-up). Other popular games included

vingt-et-un

(or blackjack), chuck (or chuck farthing, a cointossing game), three-card monte and faro.

Of all the passengers who ever boarded a Mississippi River steamboat, none were more remembered, or more written about, than the professional gamblers. At first they were regarded merely as very good players and accepted by fellow passengers as such. “The card tables of a steamer were free to all persons of gentlemanly habits and manners,” George Byron Merrick wrote. “The gambler was not excluded from a seat there on account of his superior skill at play; or, at least, it was an exceedingly rare thing for one person to object to another on these grounds. Pride would not permit the humiliating confession.”

11

Curiously, men who refused to associate with gamblers in ordinary circumstances ashore felt themselves in no way compromised by sharing a card table with them on a Mississippi River steamboat.

Pots were not big on the upper Mississippi, the playing passengers not being the wealthy planters that many passengers on the lower Mississippi were. Some did come aboard wearing broad money belts, though, laden with twenty-dollar gold pieces, and gamblers were usually satisfied to pick up two or three hundred dollars a week from those gold-bearing passengers.

Collusion was common. The professional gamblers often worked in pairs, coming aboard separately, pretending not to know each other, not speaking to each other until introduced, usually by an intended victim. They were convincing actors, playing a variety of roles to help lure suckers into a game. “At different times they represented all sorts and conditions of men — settlers, prospectors, Indian agents, merchants, lumbermen, and even lumber-jacks,” Merrick wrote, “and they always dressed their part, and talked it, too. To do this required some education, keen powers of observation, and an all-around knowledge of men and things. They were gentlemanly at all times — courteous to men and chivalrous to women. While pretending to drink large quantities of very strong liquors, they did in fact make away with many pint measures of quite innocent river water, tinted with the mildest liquid distillation of burned peaches.... They kept their private bottles of colored water on tap in the bar, and with the uninitiated passed for heavy drinkers.”

12

The professionals apparently cooperated in a sort of a gamblers’ fraternity that in effect granted informal franchises to particular individuals to work particular boats and discouraged encroachment by one gambler on the territory of another. Gamblers did occasionally switch from one steamboat to another, but only by agreement with their affected brethren.

Over time, the professionals developed a successful

modus operandi

. Once they had lured one or more victims into “a friendly game,” the professionals, in the early hands of the game, would deliberately and cheerfully lose large pots to each other, and when the game had proceeded to the point where the intended victims felt comfortable and confident, one of the professionals would announce that the boat had reached his town and would disembark at, say, Prescott, Wisconsin, or Hastings, Minnesota, or Stillwater, Minnesota, and his partner would continue on to St. Paul, with the intended victims still at the card table with him, now ready to be fleeced.

“The chief reliance of the gamblers,” steamboat traveler John Morris related, “lay in the marked cards with which they played. No pack of cards left the bar until it had passed through the hands of the gambler who patronized the particular boat that he ‘worked.’ The marking was called ‘stripping.’ This was done by placing the high cards — ace, king, queen, jack, and tenspot — between two thin sheets of metal, the edges of which were very slightly concaved. Both edges of the cards were trimmed to these edges with a razor; the cards so ‘stripped’ were thus a shade narrower in the middle than those not operated upon; they were left full width at each end. The acutely sensitive fingers of the gamblers could distinguish between the marked and the unmarked cards, while the other players could detect nothing out of the way in them.”

13

The professional gambler might spend hours stripping the cards in his stateroom, then replace them in their cartons, reseal the cartons and return them to the bar to be repurchased later, the bartender obviously being in collusion with the gamblers.

ipso facto

card sharp — rather