The Great American Steamboat Race (3 page)

Read The Great American Steamboat Race Online

Authors: Benton Rain Patterson

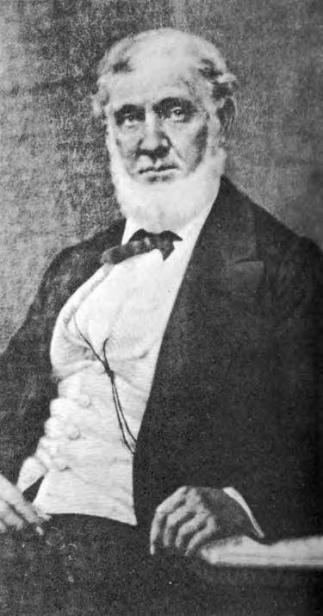

John W. Cannon, owner and captain of the

Robert E. Lee

. Cannon was goaded into racing the

Lee

against the

Natchez

by Tom Leathers, his business rival and personal adversary, with whom he had tangled in a fistfight in a New Orleans saloon.

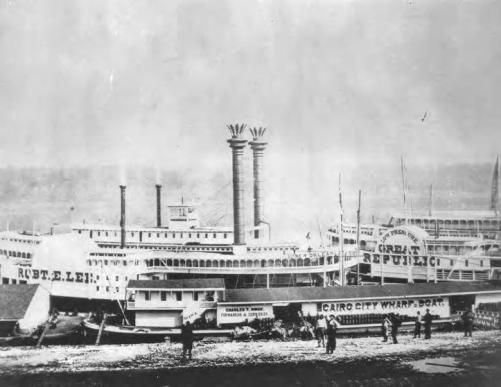

The

Robert E. Lee

docked beside the

Great Republic

. The

Lee

was built for John Cannon in New Albany, Indiana, in 1866, the year after the Civil War ended. When its name was painted on its wheel housing, the boat had to be towed to the Kentucky side of the Ohio River to prevent its being burned by irate Northerners who objected to its being named for the Confederacy ’s most famous general (Library of Congress).

Actually, Cannon was believed to have been sympathetic to the Union, though after nearly a lifetime in the steamboat business, he, like Leathers, had many friends and business associates in both the North and South. Cannon was reported to be a friend of Union general Grant, and some suspected that he named his boat after the Confederate general to win approval in the South, where most of his customers were, and to compensate for his known Northern sympathies. Leathers, who refused to fly a U.S. flag on the

Natchez

even though the war had ended and who effected a sort of uniform of Confederate gray while captaining his boat, had at one time been arrested for suspected Union sympathies during the war, only to be pardoned by his friend Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president and former United States senator from Mississippi.

Cannon had managed to make a small fortune out of the war. He took his steamer

General Quitman

up the Red River and kept it hidden until Union forces had taken complete control over the Mississippi, then came steaming down from Shreveport to the Mississippi and up to St. Louis with a boatload of cotton that he had bought at depressed prices from planters unable to sell it on the usual markets. He then sold it for several times the price he had paid, netting a profit estimated at $250,000. With that bankroll, Cannon had little trouble paying the $230,000 that the

Robert E. Lee

cost him,

6

or being able to afford two homes, one in New Orleans and the other in Frankfort, Kentucky, where he and his wife spent their summers.

The completed

Robert E. Lee

arrived in New Orleans on its maiden voyage in October 1866 and quickly proved itself as a fast steamer, setting new speed records and winning over flocks of new customers — while at the same time raising the ire and jealousy of Tom Leathers, who for a short time after the war had worked for Cannon as captain of the

General Quitman

. Cannon was said to have taken pleasure in having his rival work for him. The relationship between the two men remained a stormy one, though, and Leathers had left the

General Quitman

to command another steamer, the

Belle Lee

, in 1868.

In November 1868 their hostility toward each other broke out in a quarrel in a New Orleans saloon, while both apparently were under the influence, and a fistfight resulted. “Very little claret was drawn,” a waggish reporter commented while declaring that “Capt. Cannon had the best of the fight.”

7

After that scuffle, they refused to speak to each other or even to exchange whistle salutes as their boats passed each other on the river, which was the custom among steamboatmen.

Reserved though he was, Cannon was not one to back away from a fight. In 1858, when he was master of the

Vicksburg

, he fired a pilot named Allen Pell and when Pell demanded to know the reason, Cannon, apparently in no uncertain terms, told him. The blunt answer drew an angry threat from Pell, and Cannon, thick-bodied and strong-armed, drove a heavy fist into Pell’s face in reaction, staggering him. Pell then pulled a knife from the sleeve of his coat, and Cannon, undaunted, grappled with Pell for the knife and was stabbed just above the groin. Cannon recovered and although his dealings with Pell were forever ended, Cannon had no qualms about hiring one of Pell’s relatives, James Pell, as one of his pilots aboard the

Robert E. Lee

.

In 1869, determined to best Cannon and boasting that he would drive the

Robert E. Lee

off the river, Leathers ordered a shipyard in Cincinnati to build him a boat, a new

Natchez

, that would outrace Cannon’s speedy, elegant

Robert E. Lee

. Leathers had come out of the war not nearly so well off

The

Natchez

, the sixth steamer to bear that name. It was built for Tom Leathers in Cincinnati in 1869 at a cost of $200,000 and was designed, by Leathers’ orders, to outrun the swift

Robert E. Lee

(National Mississippi River Museum and Aquarium, Captain William D. Bowell Sr. River Library).

as Cannon, having lost his boat during the conflict. He found financial backers, however, the chief of whom was Cincinnati businessman Charles Kilgour. The new

Natchez

, completed at a cost of some $200,000, began its first voyage down the Ohio and into the Mississippi on October 3, 1869. In June 1870 he was said to still owe $90,000 on the boat.

Cannon had repeatedly declined challenges to pit his boat against the

Natchez

. For a while, ever since the

Lee

had first been put into service, Cannon had run it between New Orleans and Vicksburg, the same run that the

Natchez

made. The

Lee

would leave New Orleans every week on Tuesday and the

Natchez

on Saturday. Fans of the two boats developed a sense of rivalry between them, each group sure of the superiority of their favorite and urging the two captains to race them and settle the question of which was faster. As if to dampen the enthusiasm for a race, Cannon altered the

Robert E. Lee

’s run in the spring of 1870. Its new schedule had it run between New Orleans and Louisville, leaving New Orleans every other Thursday. Leathers also dropped out of the New Orleans–Vicksburg trade that spring and he began running the

Natchez

between New Orleans and St. Louis, leaving New Orleans on Saturdays.

Calls for a race increased despite the change in schedules. Leathers was all for it. Throwing down his gauntlet, Ol’ Push announced that the

Natchez

, instead of leaving New Orleans on Saturday as usual, would leave on the same day, at the same time, that the

Robert E. Lee

left, forcing Cannon to run the

Lee

against him. Cannon still resisted, but on his return trip from Louisville in late June his shippers along the Ohio River repeatedly urged him to race. At last he gave in to the pressures coming from customers, from newspapers in the river towns from New Orleans to Louisville, from planters and merchants and other businessmen, from gambling interests — and from Leathers himself. Still, after he had agreed to the contest, he denied reports that he would engage in the race and had a notice to that effect published in successive editions of the

Picayune

, including the edition published on the morning of the day the race was to begin:

A CARD

Reports having been circulated that steamer R.E. LEE, leaving for Louisville on the 30th June, is going out for a race, such reports are not true, and the travelling community are assured that every attention will be given to the safety and

The running and management of the Lee will in no manner be affected by the departure of other boats.

John W. Cannon, Master Leathers, likewise apparently fearing repercussions from some passengers and shippers, also had a denial published in the

Picayune

:

A CARD TO THE PUBLIC

Being satisfied that the steamer NATCHEZ has a reputation of being fast, I take this method of informing the public that the reports of the Natchez leaving

All passengers and shippers can rest assured that the Natchez will not race with any boat that will leave here on the same day with her. All business intrusted to my care, either in freight or passengers, will have the best attention.

Master, Steamer Natchez

The

Robert E. Lee

arrived back in New Orleans from Louisville in the evening of Tuesday, June 28, and Cannon, having by then agreed to the race, having begun elaborate preparations for it and having become determined that his hated rival would not beat him, immediately ordered his magnificent

Lee

stripped of every possible impediment to speed. To reduce wind resistance, the window sash was removed from the front and back of the pilothouse, and the front double doors and the big aft windows of the main cabin were likewise removed. The decks aft of the paddle wheels had every other plank taken up to allow the spray from the wheels to quickly fall through the decks. The steam-escape pipes, the freight-lifting derricks, the spare anchors and extra mooring chains, everything that could be spared on the main deck and in the hold was taken ashore, along with virtually everything else that was portable, including most of the staterooms’ furniture and decorative accessories, and all freight had been refused. Left in place, however, was the large, handsome portrait of the boat’s namesake, General Lee.

The passenger list had been kept as short as possible. Captain Cannon announced to those passengers who already held tickets that plans had changed and the

Lee

was headed for St. Louis, not Louisville, and there would be no stops on the way. Passengers who had bought passage to Louisville and other destinations on the Ohio would be transferred to another steamer at Cairo, Illinois.

Even so, Cannon would have to accommodate some seventy passengers, including friends and some fellow captains, business associates and VIPs, all of them presumably eager to be participants in the history-making race. Two who perhaps were not so eager were the twenty-six-year-old carpetbagger governor of Louisiana, Henry Clay Warmoth, and his close friend and political ally, Doctor A.W. Smyth, chief surgeon at Charity Hospital in New Orleans. Smyth was also a close friend of John Cannon, and the two men — Smyth and Warmoth — had just arrived at the New Orleans riverfront on a steamer from Baton Rouge, where Warmoth had presented diplomas to graduates at Louisiana State University’s commencement exercises. What the two men encountered when they reached the wharf was the largest crowd the governor had ever seen in New Orleans. On the spur of the moment, Smyth had suggested they board the

Robert E. Lee

to greet Captain Cannon and wish him well. Delighted to have them aboard, Cannon insisted they stay for the ride. “Captain Cannon pressed us to go with him,” Warmoth wrote later, the event evidently a memorable one, “and, as we were carried away by the excitement and enthusiasm, we accepted the invitation.”

8

Leathers, supremely confident of the

Natchez

’s prowess, had made no such preparations. The only concession he had made was the removal of the boat’s landing stage that swung from a derrick and which he acknowledged could catch the wind and slow the vessel somewhat. He had booked ninety passengers aboard the

Natchez

, with destinations requiring stops at Natchez, Vicksburg, Greenville, Memphis and Cairo. Others intending to board the boat would be waiting for it along the levee upriver from New Orleans. Leathers had also taken on a load of freight, evidently considering this run to St. Louis to be business as usual, only made at a greater speed than his rival who, he apparently believed, would also make a more or less normal trip.

The

Natchez

’s freight and passenger load would add considerable weight to the vessel, but despite it, Leathers’s boat would draw but six and a half feet of water, a foot less than the stripped and lightened

Robert E. Lee

. The difference in draft could be important in the race, and not only because the shallower-draft vessel would meet less resistance in the water. The Mississippi was reported to be falling, increasing the danger of a deep-draft boat’s running aground on the river bottom.

Other than their draft and a difference in their length and freight capacity, the two steamers, both side-wheelers, were about equal in size and equipment. The

Robert E. Lee

was 285 feet in length and forty-six feet in the beam; the

Natchez

was 303 feet long and forty-six feet in the beam. The height of the

Robert E. Lee

to its pilothouse was thirty and a half feet; the height of the

Natchez

was thirty-three feet. The

Robert E. Lee

’s paddle wheels were thirtyeight feet in diameter and seventeen feet wide. The

Natchez

’s paddle wheels were forty-two feet in diameter and eleven feet wide. Each boat had eight boilers, the

Natchez

’s being slightly larger (thirty-three feet long ) than the

Robert E. Lee

’s (twenty-eight feet) and capable of generating higher pressure (160 pounds) than the

Robert E. Lee

’s boilers (110 pounds). The engines were also similar. The

Robert E. Lee

’s cylinders were forty inches in diameter with a ten-foot stroke; the

Natchez

’s cylinders were thirty-six inches in diameter with a ten-foot stroke.

9

To make sure, as sure as could be made, that the

Lee

was complying — and would continue to do so — with steamboat safety regulations, a U.S. steamboat inspector, a man named Whitmore, came aboard the vessel and examined the safety valves on each of the eight boilers. On each valve that could be locked, after locking it, he placed the government’s lead seal. Engineers would not then be tempted to manipulate the safety valves to increase steam pressure.

At fifteen minutes to five

P

.

M

., a quarter hour before the announced departure time for both boats, Captain Cannon gave three tugs on the

Robert E. Lee

’s ship’s bell to signal it was time for visitors to hurry ashore and for passengers to find their staterooms or a place at the rails. Captain Leathers immediately followed with three clangs on the

Natchez

’s bell. The last of the visitors having hustled ashore, the

Lee

’s mate shouted the order for the landing stage to be hauled in. As thick, black smoke erupted from the

Robert E. Lee

’s soaring chimneys, its bell sounded once more, an axe blade fell and severed the bowline that bound the vessel to the wharf, and the axe wielder suddenly raced for the end of the landing stage, grabbed it and held on as it came sliding onto the main deck.

Instantly then, minutes short of five o’clock, the big, grand vessel, its white woodwork gleaming in the afternoon sun, moved stern first into the streaming current of the Mississippi River, its giant paddle wheels churning a froth in the muddy flow.

The slightly early start had been carefully arranged by Cannon. He had gathered his officers together at four o’clock and given them instructions which, according to one of the assistant engineers, John Wiest, went as follows: “I want everybody aboard at five o’clock. The pilot in his house, but not in sight, the engineers at the throttle valves, the mate to have only one stage out and that at a balance so that the weight of one man on the boat end will lift it clear of the wharf. There will be a single line out, fast to a ring bolt, with a man stationed there, axe in hand, to cut and run for the end of the stage the moment he hears a single tap of the bell, and come aboard on the run or get left.”

10

Knowing Leathers’s reputation for making sudden fast starts against competitors, Cannon had now out-fast-started him. The

Lee

had been docked just below the

Natchez

, and as it backed out from the wharf and made a crescent-shaped turn to head its bow upriver, the

Natchez

was forced to wait for Cannon to straighten out the

Lee

, lest the

Natchez

back across the

Lee

’s bow, or possibly into it. Once headed upstream, the

Robert E. Lee

fired its signal cannon as it passed St. Mary’s Market, just above Canal Street, the official starting point for timing all steamboat voyages from New Orleans. The time was a minute and forty-five seconds before five o’clock.

11

As soon as the

Lee

had moved out of its way, the

Natchez

, distinguishable from a distance by its bright-red chimneys, backed away from the wharf, straightened out and with a surge of power steamed up to St. Mary’s Market, firing its signal cannon as it passed, the gun’s deep

boom

resounding over the noise of the yelling crowds on both sides of the river. The time then was two minutes after five o’clock.

12

•

2 •