The Great Big Book of Horrible Things: The Definitive Chronicle of History's 100 Worst Atrocities (14 page)

Authors: Matthew White

The whole of Gaul smoked on a single funeral pyre.

2

Stopping the invasion was not the highest priority at court. Honorius was more worried that Stilicho was becoming too powerful, so he had him assassinated in 408.

Seeing the chaos unfold on the continent, Constantine, the commander of the Roman army in Britain, declared himself emperor of the Western Empire. He crossed into Gaul to assert his claim, leaving the Britons to fend for themselves under an independence they didn’t want.

With loyal troops so scarce, Honorius was in no position to fight Constantine. Instead, he was forced to accept him as co-emperor, but before Emperor Constantine III could settle in and enjoy himself, one of his own generals rebelled and raised a third emperor. After this, it gets even more complicated. Other garrisons took sides and pretty soon all of the Romans in northwest Europe were fighting each other. Eventually, however, all of the Roman usurpers and their families were safely dead. Severed heads were hoisted triumphantly on poles all across the land—Constantine’s among them.

Safe for the moment, Honorius now had to promote Constantius, a loyal general who had saved his skin in the recent conflict, to co-emperor. Meanwhile, two other tribes had slipped into the unguarded Roman provinces behind the Vandals. The Franks, who had earlier settled as federates in the Rhine delta, now spread deeper into the land that would eventually be named after them (France). The Burgundians did likewise, ending up in Burgundy. Local Roman officials were forced to pay tribute to these tribes until someone could come and chase them away. It would take longer than anyone suspected.

Although the continent still remained under (nominal) Roman control, Emperor Honorius sent a letter to the Britons declaring them officially on their own. There was nothing he could do for them. Over the next few decades, tribe after tribe of barbarians—Picts, Scots, Angles, Saxons, and Jutes—from several directions—Ireland, Scotland, and Denmark—took advantage of the opportunity and plunged Britain into a violent, unchronicled age. With no real defender riding to their rescue, the helpless Britons had to dream one, and the legend of King Arthur was born.

The Sack of Rome

Meanwhile Alaric returned with his Visigoths and extorted a massive ransom from the city of Rome in 409. When he presented his demands at the gates of the city, the Romans were shocked. What had he left for them to keep? “Your lives,” he answered.

This kept Alaric financed for about a year, but then he returned, seized the city, and looted for several days in 410. Although Ro

me wasn’t the capital anymore and the looting was more robbery than wanton destruction, the fall of Rome shocked the civilized world. Clearly whatever was happening was more than just another dynastic dispute.

The Roman Empire is like the dinosaurs. Both are more famous for being gone than for having survived all those centuries; howe

ver, the city of Rome had remained unpillaged by foreigners for eight hundred years (390 BCE–410 CE). This is extraordinary, even by modern standards. For a sense of perspective, consider some other capital cities that foreign troops have occupied at one time or another in the past four hundred years—only half the number of years Rome remained unconquered:

Addis Ababa (1936), Athens (1826, 1941), Baghdad (1623, 1638, 1917, 2003), Beijing (1644, 1860, 1900, 1937, 1945), Berlin (1760, 1806, 1945), Brussels (1914, 1940), Buenos Aires (1806), Cairo (1799, 1882), Copenhagen (1807, 1940), Delhi (1761, 1783, 1803, 1857), Havana (1762, 1898), Kabul (1738, 1839, 1879, 1979, 2001), London (1688), Madrid (1706, 1710, 1808), Manila (1762, 1898, 1942), Mexico City (1845, 1863), Moscow (1605, 1610, 1812), Nanjing (1937), Paris (1814, 1871, 1940), Philadelphia (1777), Pretoria (1900), Rome (1798, 1808, 1849, 1943, 1944), Seoul (1910, 1945, 1950, 1951), Tehran (1941), Tokyo (1945), Vienna (1805, 1809, 1938, 1945), Washington (1814)

Unraveling

By now, trouble was so thick that individual problems had to wait in line for the chance to come crashing down on the empire. Compared to the other choices hanging over Rome, the Visigoths didn’t look so bad after all. Sure, they looted Rome and killed Emperor Valens, but at least they weren’t the Huns or the Vandals. From this point on, the Visigoths played the role of Rome’s friendly barbarians.

Among the booty carried off from Rome was Emperor Honorius’s twenty-year-old sister, Galla Placidia, and to solidify the growing alliance between the empire and the Visigoths, they were allowed to keep her. She married Athaulf, the new king who had succeeded Alaric, and the tribe was resettled in southern Gaul and given generous rights to tax local Roman citizens.

Eventually Athaulf was murdered by a servant in a coup, and the widow Placidia was bound and parad

ed through town in humiliation.

3

When a new Visigothic king put down the uprising, Placidia made her way back to Ravenna, where Honorius married her to his co-emperor Constantius, who didn’t live very long either.

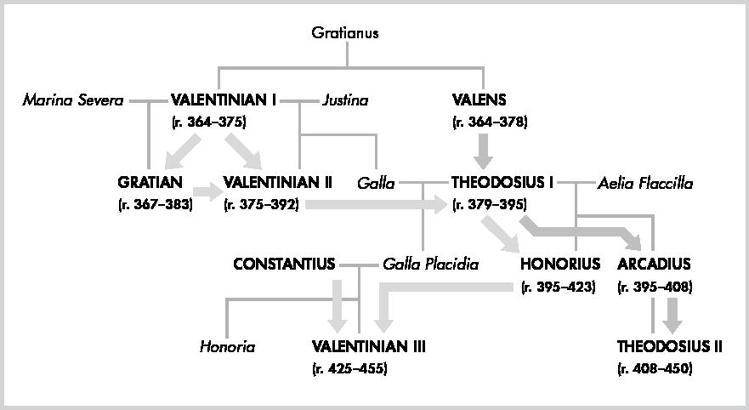

After Honorius died in 423, a usurper, Johannes, took over until the Eastern emperor’s army arrived to place Valentinian, the six-year-old nephew of Honorius and son of Constantius, on the throne in 425. Valentinian III would be the last Roman emperor to spend any length of time on the Western throne, although he never quite became the actual master of the empire. His mother, Galla Placidia, ruled as regent, and she was eminently qualified. After all, she was the daughter, wife, mother, sister, granddaughter, aunt, and niece of emperors, so at least she knew her way around the palace. As the years progressed, however, the general Flavius Aetius came to exercise more and more power.

By now, the barbarians had divided Spain among themselves and broken the local Roman army, so the empire called in a favor from the Visigoths, who rode to Spain and wiped out the Asding tribe of Vandals, leaving only the Siling tribe to carry on the proud Vandal name.

Meanwhile, the Roman commander in North Africa, Boniface, was up to something. Galla Placidia wasn’t sure what he was planning, but he seemed to be consolidating more power than a provinc

ial could be allowed, so she summoned him back to Italy to explain. When Boniface stayed put, she sent a Roman army to insist, so Boniface offered half of North Africa to the Siling Vandals in exchange for their help. Still under pressure from the Visigoths, the Vandals gladly abandoned Spain and crossed the Strait of Gibraltar in 429. Suddenly faced with two enemies in Africa, Placidia reconciled with Boniface, who promptly turned against the Vandals.

The Vandals, however, easily routed every Roman army sent against them and began the systematic conquest of North Africa, city by city. One Vandal siege trapped Saint Augustine in the city of Hippo, where he died in 430 still besieged. In 439, the Vandals finally took the provincial capital, Carthage. This gave them control of the grain supply that fed Rome at this point in history. By now, they had built a fleet with which to raid up and down the Mediterranean coast, attacking peaceful seaside communities that hadn’t seen a pirate fleet in five hundred years.

4

Attila

By this time, the Huns had arrived at the river frontiers of the Roman Empire and began to strike into the Balkans. An ecclesiastical chronicler described it: “There were so many murders and blood-lettings that the dead could not be numbered. Ay, for they took captive the churches and monasteries and slew the monks and maidens in great quantities.”

5

The Eastern emperor, Theodosius II, surrendered the south bank of the Danube to Hun control and paid a huge ransom for the Huns to not come any closer, but the Western emperor had too many other priorities and not enough cash to protect his half. The Huns camped across the Danube and raided into Roman Pannonia (western Hungary) for a quick pillage now and then to keep in practice.

Back in Italy, the empire’s attention was diverted by one of the most destructive episodes of sibling rivalry in history. Valentinian’s sister Honoria became romantically involved with the manager of her estates, which was

politically dangerous, so they conspired to overthrow her brother before he found out. Unfortunately they were too late; he already knew. Valentinian beheaded her lover and would have done the same to his sister except that Placidia intervened. The imperial family then tried to force Honoria into marriage with an aged and safe senator, but she adamantly refused. Finally everyone agreed that Honoria would be packed off to Constantinople for safe keeping.

Having lost the first round, Honoria secretly wrote to Attila, king of the Huns, to propose a marriage alliance, entrusting her eunuch to take the letter to Attila, along with her ring to guarantee authenticity. When this

new plot was discovered, the Eastern emperor Theodosius II quickly dumped the problem back on Ravenna, shipping Honoria home with the advice that his cousin Valentinian should agree to the marriage for political expediency. Placidia agreed, but Valentinian was furious. It took all of Placidia’s influence just to talk him out of killing his sister for the trouble she had caused; however, both Placidia and Theodosius II died about this time, which left the final decision to Valentinian, who would have nothing to do with any such union. Honoria was married to a minor Roman and exiled; she disappears from history after this.

6

Unfortunately Attila was not so easy to remove. He had been promised an imperial bride, and dammit, someone had better pay up. He rode against the empire to claim Honoria, along with an expected dowry of half the empire. Attacking over the Rhine, Attila swept across the north of Gaul, leaving behind a reputation for destructiveness that would last over a thousand years. A chronicler described the opening gambit: “The Huns, issuing from Pannonia, reached the town of Metz on the vigil of the feast of Easter, devastating the whole country. They gave the city to the flames and slew the people with the edge of the sword, and did to death the priests of the Lord before the holy altars.”

7

The Huns advanced as far as Orleans, which withstood their siege, so they rode off to find an easier target. Soon the combined army of Romans and Visigoths under the command of Aetius caught up with the Huns and beat them at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains in 451. This was the last victory ever achieved by the Western Roman army, and we know almost nothing about it. Not only have archaeologists never found the site, but also they don’t even know where to start looking. In the histories that have come down to us, the sizes of the armies and the mountains of dead have been exaggerated beyond recognition.

8

After a retreat and regroup, Attila crossed the Alps into Italy, destroying the city of Aquileia and driving the survivors into hiding in the marshes of a nearby lagoon, where they would build a new city, Venice. As the Huns headed deeper into Italy, another looting of Rome looked likely, but Attila changed his mind after meeting with local notables, such as Pope Leo. No one knows why Attila turned back and went home, but candidates include everything from the miraculous appearance of Saints Peter and Paul, to an outbreak of plague, to the realization that he had overstretched his resources, to a simple payoff.

Back in Barbarianland in 453, Attila died drunk in bed on his wedding night after a great effusion of blood from his nose. Within a year, all of the Germanic vassals had thrown off the yoke of the Huns, who quickly retreated to the Ukrainian steppe.

9

By this time, General Aetius had become too powerful and a threat to Valentinian. One day in 454, when Aetius was delivering a financial report to the emperor, Valentinian leapt off the throne, sword in hand, and cut his general down then and there. Aetius was avenged six months later when soldiers loyal to him assassinated Valentinian.

Soon afterward, King Gaiseric of the Vandals landed an army at Ostia and attacked up the Tiber River, capturing Rome. The Vandals gave it a much more thorough shakedown than the Visigoths had, attaching their name to the whole concept of aimless destruction. When they sailed back to Carthage after a fourteen-day pillage, they carried off centuries’ worth of collected treasures, such as the gold candlestick looted from Jerusalem, and thousands of prisoners, including Valentinian’s widow and daughters. The lesser prisoners went straight into the slave markets, while the imperial family remained hostages.

10