The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia (2 page)

Read The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia Online

Authors: Peter Hopkirk

Tags: #Non-fiction, #Travel, ##genre, #Politics, #War, #History

But in piecing together this narrative, my overriding debt must be to those remarkable individuals who took part in the Great Game and who left accounts of their adventures and misadventures among the deserts and mountains. These provide most of the drama of this tale, and without them it could never have been told in this form. There exist biographies of a number of individual players, and these too have proved valuable. For the political and diplomatic background to the struggle I have made full use of the latest scholarship by specialist historians of the period, to whom I am greatly indebted. I must also thank the staff of the India Office Library and Records for making available to me numerous records and other material from that vast repository of British imperial history.

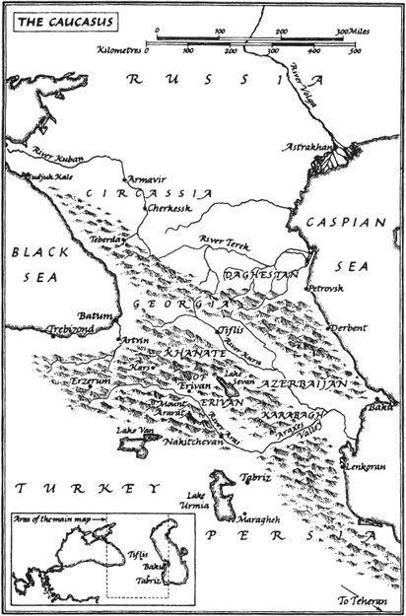

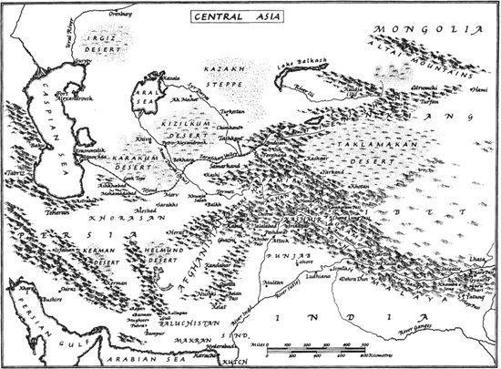

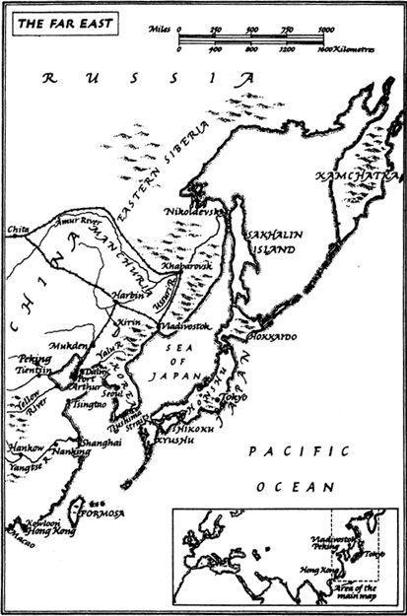

The individual to whom I perhaps owe most is my wife Kath, whose thoroughness in all things has contributed so much to the writing and researching of this, and my earlier books, at all stages, and on whom I tried out the narrative as it unfolded. In addition to preparing drafts for the six maps, she also compiled the index. Finally, I was most fortunate in having Gail Pirkis as my editor. Her eagle-eyed professionalism, calm good humour and unfailing tact proved to be an immense support during the long months of seeing this book through to publication. It is worth adding that Gail, when with Oxford University Press in Hong Kong, was responsible for rescuing from virtual oblivion a number of important works on Central Asia, at least two of them by Great Game heroes, and having them reprinted in attractive new editions.

Note on Spellings

Many of the names of peoples and places occurring in this narrative have been spelt or romanised in a variety of ways over the years. Thus Tartar/Tatar; Erzerum/Erzurum; Turcoman/Turkmen; Kashgar/Kashi; Tiflis/Tbilisi. For the sake of consistency and simplicity I have mostly settled for the spelling which would have been familiar to those who took part in these events.

Prologue

On a June morning in 1842, in the Central Asian town of Bokhara, two ragged figures could be seen kneeling in the dust in the great square before the Emir’s palace. Their arms were tied tightly behind their backs, and they were in a pitiful condition. Filthy and half-starved, their bodies were covered with sores, their hair, beards and clothes alive with lice. Not far away were two freshly dug graves. Looking on in silence was a small crowd of Bokharans. Normally executions attracted little attention in this remote, and still medieval, caravan town, for under the Emir’s vicious and despotic rule they were all too frequent. But this one was different. The two men kneeling in the blazing midday sun at the executioner’s feet were British officers.

On a June morning in 1842, in the Central Asian town of Bokhara, two ragged figures could be seen kneeling in the dust in the great square before the Emir’s palace. Their arms were tied tightly behind their backs, and they were in a pitiful condition. Filthy and half-starved, their bodies were covered with sores, their hair, beards and clothes alive with lice. Not far away were two freshly dug graves. Looking on in silence was a small crowd of Bokharans. Normally executions attracted little attention in this remote, and still medieval, caravan town, for under the Emir’s vicious and despotic rule they were all too frequent. But this one was different. The two men kneeling in the blazing midday sun at the executioner’s feet were British officers.

For months they had been kept by the Emir in a dark, stinking pit beneath the mud-built citadel, with rats and other vermin as their sole companions. The two men – Colonel Charles Stoddart and Captain Arthur Conolly – were about to face death together, 4,000 miles from home, at a spot where today foreign tourists step down from their Russian buses, unaware of what once happened there. Stoddart and Conolly were paying the price of engaging in a highly dangerous game – the Great Game, as it became known to those who risked their necks playing it. Ironically, it was Conolly himself who had first coined the phrase, although it was Kipling who was to immortalise it many years later in his novel

Kim.

The first of the two men to die on that June morning, while his friend looked on, was Stoddart. He had been sent to Bokhara by the East India Company to try to forge an alliance with the Emir against the Russians, whose advance into Central Asia was giving rise to fears about their future intentions. But things had gone badly wrong. When Conolly, who had volunteered to try to obtain his brother officer’s freedom, reached Bokhara, he too had ended up in the Emir’s grim dungeon. Moments after Stoddart’s beheading, Conolly was also dispatched, and today the two men’s remains lie, together with the Emir’s many other victims, in a grisly and long-forgotten graveyard somewhere beneath the square.

Stoddart and Conolly were merely two of the many officers and explorers, both British and Russian, who over the best part of a century took part in the Great Game, and whose adventures and misadventures while so engaged form the narrative of this book. The vast chessboard on which this shadowy struggle for political ascendancy took place stretched from the snow-capped Caucasus in the west, across the great deserts and mountain ranges of Central Asia, to Chinese Turkestan and Tibet in the east. The ultimate prize, or so it was feared in London and Calcutta, and fervently hoped by ambitious Russian officers serving in Asia, was British India.

It all began in the early years of the nineteenth century, when Russian troops started to fight their way southwards through the Caucasus, then inhabited by fierce Muslim and Christian tribesmen, towards northern Persia. At first, like Russia’s great march eastwards across Siberia two centuries earlier, this did not seem to pose any serious threat to British interests. Catherine the Great, it was true, had toyed with the idea of marching on India, while in 1801 her son Paul had got as far as dispatching an invasion force in that direction, only for it to be hastily recalled on his death shortly afterwards. But somehow no one took the Russians too seriously in those days, and their nearest frontier posts were too far distant to pose any real threat to the East India Company’s possessions.

Then, in 1807, intelligence reached London which was to cause considerable alarm to both the British government and the Company’s directors. Napoleon Bonaparte, emboldened by his run of brilliant victories in Europe, had put it to Paul’s successor, Tsar Alexander I, that they should together invade India and wrest it from British domination. Eventually, he told Alexander, they might with their combined armies conquer the entire world and divide it between them. It was no secret in London and Calcutta that Napoleon had long had his eye on India. He was also thirsting to avenge the humiliating defeats inflicted by the British on his countrymen during their earlier struggle for its possession.

His breathtaking plan was to march 50,000 French troops across Persia and Afghanistan, and there join forces with Alexander’s Cossacks for the final thrust across the Indus into India. But this was not Europe, with its ready supplies, roads, bridges and temperate climate, and Napoleon had little idea of the terrible hardships and obstacles which would have to be overcome by an army taking this route. His ignorance of the intervening terrain, with its great waterless deserts and mountain barriers, was matched only by that of the British themselves. Until then, having arrived originally by sea, the latter had given scant attention to the strategic land routes to India, being more concerned with keeping the seaways open.

Overnight this complacency vanished. Whereas the Russians by themselves might not present much of a threat, the combined armies of Napoleon and Alexander were a very different matter, especially if led by a soldier of the former’s undoubted genius. Orders were hastily issued for the routes by which an invader might reach India to be thoroughly explored and mapped, so that it could be decided by the Company’s defence chiefs where best he might be halted and destroyed. At the same time diplomatic missions were dispatched to the Shah of Persia and the Emir of Afghanistan, through whose domains the aggressor would have to pass, in the hope of discouraging them from entering into any liaisons with the foe.

The threat never materialised, for Napoleon and Alexander soon fell out. As French troops swept into Russia and entered a burning Moscow, India was temporarily forgotten. But no sooner had Napoleon been driven back into Europe with terrible losses than a new threat to India arose. This time it was the Russians, brimming with self-confidence and ambition, and this time it was not going to go away. As the battle-hardened Russian troops began their southwards advance through the Caucasus once again, fears for the safety of India deepened.

Having crushed the Caucasian tribes, though only after a long and bitter resistance in which a handful of Englishmen took part, the Russians then switched their covetous gaze eastwards. There, in a vast arena of desert and mountain to the north of India, lay the ancient Muslim khanates of Khiva, Bokhara and Khokand. As the Russian advance towards them gathered momentum, London and Calcutta became increasingly alarmed. Before very long this great political no-man’s-land was to become a vast adventure playground for ambitious young officers and explorers of both sides as they mapped the passes and deserts across which armies would have to march if war came to the region.

By the middle of the nineteenth century Central Asia was rarely out of the headlines, as one by one the ancient caravan towns and khanates of the former Silk Road fell to Russian arms. Every week seemed to bring news that the hard-riding Cossacks, who always spearheaded each advance, were getting closer and closer to India’s ill-guarded frontiers. In 1865 the great walled city of Tashkent submitted to the Tsar. Three years later it was the turn of Samarkand and Bokhara, and five years after that, at the second attempt, the Russians took Khiva. The carnage inflicted by the Russian guns on those brave but unwise enough to resist was horrifying. ‘But in Asia,’ one Russian general explained, ‘the harder you hit them, the longer they remain quiet.’

Despite St Petersburg’s repeated assurances that it had no hostile intent towards India, and that each advance was its last, it looked to many as though it was all part of a grand design to bring the whole of Central Asia under Tsarist sway. And once that was accomplished, it was feared, the final advance would begin on India – the greatest of all imperial prizes. For it was no secret that several of the Tsar’s ablest generals had drawn up plans for such an invasion, and that to a man the Russian army was raring to go.

As the gap between the two front lines gradually narrowed, the Great Game intensified. Despite the dangers, principally from hostile tribes and rulers, there was no shortage of intrepid young officers eager to risk their lives beyond the frontier, filling in the blanks on the map, reporting on Russian movements, and trying to win the allegiance of suspicious khans. Stoddart and Conolly, as will be seen, were by no means the only ones who failed to return from the treacherous north. Most of the players in this shadowy struggle were professionals, Indian Army officers or political agents, sent by their superiors in Calcutta to gather intelligence of every kind. Others, no less capable, were amateurs, often travellers of independent means, who chose to play what one of the Tsar’s ministers called ‘this tournament of shadows’. Some went in disguise, others in full regimentals.