The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia (47 page)

Read The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia Online

Authors: Peter Hopkirk

Tags: #Non-fiction, #Travel, ##genre, #Politics, #War, #History

The British retreat from Afghanistan in 1842. The last stand of the 44th at the village of Grandmark, where their bones can still be found

Above:

The ill-fated Captain Conolly

(right)

and Colonel Stoddart being led in chains to the Emir of Bokhara’s verminous dungeon – a Victorian artist’s impression

Left:

The notorious Emir Nasrullah of Bokhara who, emboldened by the British catastrophe in Afghanistan, had Conolly and Stoddart beheaded in June 1842.

Sir Alexander Burnes (1805-41), in Afghan dress. He was finally hacked to death by a fanatical Kabul mob

General Konstantin Kaufman (1818-82), first Governor-General of Turkestan, and architect of Russia’s conquests in Central Asia

A classic Great Game image – scanning the passes, with a rifle-case to steady the telescope

Cossacks manning a machine-gun post in the Pamirs – scene of Russia’s last thrust towards India

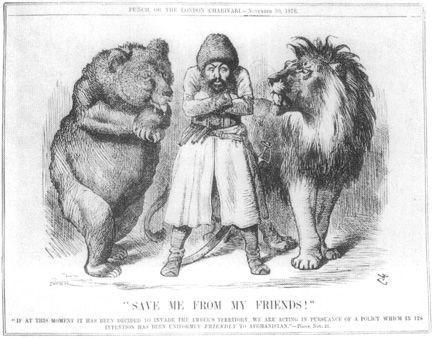

A contemporary cartoon from

Punch

depicting the pressures applied to Abdur Rahman by his two superpower neighbours

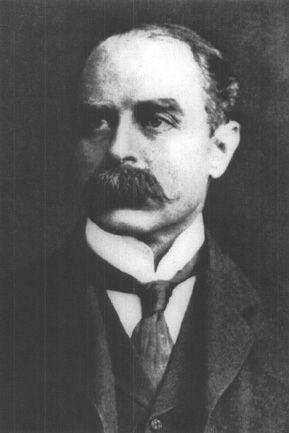

Francis Younghusband (1863-1942), at the time of the Lhasa Expedition of 1904, the last major move by either side in the Great Game

·23·

The Great Russian Advance Begins

‘Where the imperial flag has once flown,’ Tsar Nicholas is said to have decreed, ‘it must never be lowered.’ Nor did his son Alexander have any reason to think differently. To those serving on Russia’s Asiatic frontiers the inference soon became clear. Raise the two-headed eagle first, and ask permission afterwards. Those who did just that found that they were rarely, if ever, repudiated. This turning of a blind eye to such expropriations by St Petersburg was to coincide with the rise of a new and aggressive breed of frontier officer. Not surprisingly, in view of their country’s defeat in the Crimean War, they were Anglophobes to a man. Between them, during the middle years of the nineteenth century, they were to add vast new tracts of Asia to Alexander’s domains.

‘Where the imperial flag has once flown,’ Tsar Nicholas is said to have decreed, ‘it must never be lowered.’ Nor did his son Alexander have any reason to think differently. To those serving on Russia’s Asiatic frontiers the inference soon became clear. Raise the two-headed eagle first, and ask permission afterwards. Those who did just that found that they were rarely, if ever, repudiated. This turning of a blind eye to such expropriations by St Petersburg was to coincide with the rise of a new and aggressive breed of frontier officer. Not surprisingly, in view of their country’s defeat in the Crimean War, they were Anglophobes to a man. Between them, during the middle years of the nineteenth century, they were to add vast new tracts of Asia to Alexander’s domains.

One such officer was Count Nikolai Ignatiev, a brilliant and ambitious young political, who enjoyed the ear of the Tsar, and burned to settle his country’s scores with the British. As the latter would soon learn to their cost, he was to prove himself a consummate player in the Great Game. While serving as military attaché in London during the Indian Mutiny, he had repeatedly urged his chiefs in St Petersburg to take full advantage of Britain’s weakness in order to steal a march on her in Asia and elsewhere. Although he attempted to conceal his anti-British feelings, and enjoyed considerable popularity in London society, he did not entirely fool the Foreign Office. Describing him in a confidential report as a ‘clever, wily fellow’, it had him closely watched after a London map dealer informed the authorities that he had been discreetly buying up all available maps of Britain’s ports and railways.

In 1858, aged 26 and already earmarked for rapid promotion, he was chosen by Alexander to lead a secret mission to Central Asia. His task was to try to discover how far the British had penetrated the region, politically and commercially, and to undermine any influence which they might already have acquired in Khiva and Bokhara. For the Tsar was concerned about reports reaching Russian outposts on the Syr-Darya that British agents were becoming increasingly active in the region. If this were to turn into a race for the valuable markets of Central Asia, then St Petersburg was determined to win it. Ignatiev was instructed therefore to try to establish regular commercial links with both Khiva and Bokhara, if possible securing favourable terms and assured protection for Russian traders and goods. He also had orders to gather as much military, political and other intelligence as he could, including an evaluation of the khanates’ capacity for war. Finally he was to discover all he could about the navigability of the Oxus, and about the routes leading into Afghanistan, Persia and northern India.

Ignatiev’s mission, nearly a hundred strong, including a Cossack escort and porters, reached Khiva in the summer of 1858. The Khan had agreed to receive them, and they brought with them an impressive array of gifts, including an organ. These proved too bulky to be transported across the desert, having instead to be ferried across the Aral Sea and up the Oxus, thus providing the Russians with the opportunity to survey the latter’s lower reaches. It was a Great Game subterfuge borrowed from the British, who had charted the River Indus in somewhat similar manner nearly thirty years previously. Nor was the gift of an organ to an Eastern potentate entirely original, the British Levant Company having presented the Turkish Sultan with one more than two centuries earlier. The Khan was not that easily fooled, however. He received Ignatiev politely, accepted the gifts, but adamantly refused to let the Russian vessels proceed any further up the Oxus towards Bokhara. Even so, Ignatiev persuaded the Khan to open his markets to Russian merchants, only to see this collapse at the last moment when a Persian slave sought asylum aboard a Russian vessel. Nonetheless he left Khiva for Bokhara with a good deal of valuable intelligence, not to mention hawkish views on the need to cut the Khan down to size by annexing his territories.