The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia (54 page)

Read The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia Online

Authors: Peter Hopkirk

Tags: #Non-fiction, #Travel, ##genre, #Politics, #War, #History

Had Sir John Lawrence still been Viceroy, no official notice would have been taken of their views. Indeed, they would almost certainly have been severely reprimanded for meddling in affairs of state, as Moorcroft had been half a century earlier. But during their absence he had retired and had been succeeded by a younger Viceroy with a more open mind. India’s new chief was Lord Mayo, who had not only visited Russia but had also written a two-volume work about the country. It was not surprising, therefore, that he was eager to hear what these two enterprising young travellers had to say about Yakub Beg and Russian machinations beyond the Pamir and Karakoram passes.

Their warnings, however, would not go unchallenged by the military establishment, even if none of the latter had ever set foot themselves in the passes they discussed with such intimacy. ‘It is conceivable’, one War Office colonel wrote, ‘that 10,000 Kirghiz horsemen might

be

able to traverse a difficult road . . . with nothing but what can be carried at the saddle bow. But turn these into European soldiers with their trains of artillery, ammunition, hospital supplies, and the innumerable requirements of a modern army, and the case is totally different. The resources of the country that might suffice for the one would be utterly insufficient for the other.’ However, if Shaw and Hayward had failed to convince the defence chiefs that the Cossacks were about to swarm down through the northern passes into India, they did succeed in opening up a great debate on the general vulnerability of the region to Russian incursion. And they did more than that, for they also managed to interest the new Viceroy in Yakub Beg’s diplomatic overture. Their hand was strengthened here by the timely arrival in India of the latter’s special envoy.

Lord Mayo was convinced that India’s best defence lay, not in forward policies or military adventures, but in the establishment of a chain of buffer states friendly to Britain around its vast and thinly guarded frontiers. The most important of these was obviously Afghanistan, now ruled by Dost Mohammed’s son Sher Ali, with whom Calcutta enjoyed cordial relations. Here was Mayo’s chance to add another link to the chain by making a friend of Yakub Beg. With these two powerful rulers as Britain’s allies, India had little to fear from the Russians. In a crisis Mayo was willing to assist them with arms and money, and perhaps even military advisers. With a handful of British officers and generous helpings of gold, he declared, ‘I could make of Central Asia a hotplate for our friend the Russian bear to dance on’. It was much what Moorcroft had proposed many years before when he outlined to his superiors a strategy whereby British officers commanding local irregulars would halt an invading Russian force in the high passes by rolling huge boulders down on it from above.

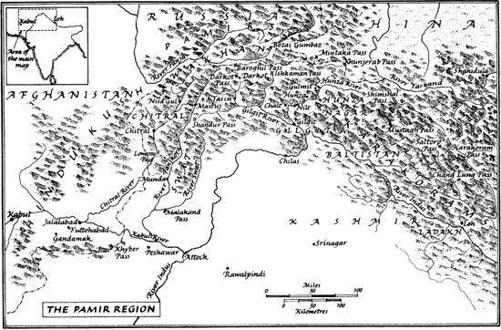

Lord Mayo gave orders for a small British diplomatic mission, thinly disguised as a purely commercial one, to return with Yakub Beg’s special envoy to Kashgar. It was led by Sir Douglas Forsyth, a senior political officer. Its purpose was to make exploratory contacts with this powerful Muslim ruler who, it appeared, preferred the friendship of the British to that of the Russians, and also to investigate the possibility of establishing regular caravan traffic across the Karakorams. Sir John Lawrence, fearing the political consequences of the latter, had always opposed any such initiatives. But Mayo took the opposite view, seeing commerce as a means of extending British influence into Central Asia with the minimum of risk. He also saw it as a way of combating the growing influence of the Russians, with their manifestly inferior goods, in the states beyond India’s northern frontiers. Nor was he blind to the commercial advantage to be gained from opening up Kashgaria where, according to Robert Shaw, there were anything up to sixty million potential customers, each one a tea-drinker and a cotton-wearer, eagerly awaiting the British caravans. Shaw was invited by Mayo to join the Forsyth mission, and immediately accepted. George Hayward, the loner, had other plans. He too was preparing to venture into the unknown once again. His objective was the Pamirs, beyond whose towering peaks and unmapped passes lay the nearest Russian outposts. And this time no one was going to stop him.

·26·

The Feel of Cold Steel Across His Throat

When word of George Hayward’s plans reached the ears of the authorities, considerable pressure was brought to bear on him to call off his expedition. Not only were the dangers to a lone European traveller in this wild and lawless region immense, but it was also a highly sensitive area politically. Indeed, it was for just such hazardous operations as this that the Pundits had been conceived and trained. To a man like Hayward, however, the risks merely made it more attractive. In a revealing moment he had once written to Robert Shaw: ‘I shall wander about the wilds of Central Asia possessed of an insane desire to try the effects of cold steel across my throat.’ From anyone else this would simply have sounded like bravado. But Hayward, as his few friends would confirm, genuinely relished danger, though in retrospect it appears more like a death wish. Having no close ties or family, moreover, he had little to lose, and a great deal to gain if he succeeded. For on one thing everyone was agreed. Hayward was a first-rate explorer and a surveyor of great skill. If he did get back alive, his discoveries were likely to be of immense value.

When word of George Hayward’s plans reached the ears of the authorities, considerable pressure was brought to bear on him to call off his expedition. Not only were the dangers to a lone European traveller in this wild and lawless region immense, but it was also a highly sensitive area politically. Indeed, it was for just such hazardous operations as this that the Pundits had been conceived and trained. To a man like Hayward, however, the risks merely made it more attractive. In a revealing moment he had once written to Robert Shaw: ‘I shall wander about the wilds of Central Asia possessed of an insane desire to try the effects of cold steel across my throat.’ From anyone else this would simply have sounded like bravado. But Hayward, as his few friends would confirm, genuinely relished danger, though in retrospect it appears more like a death wish. Having no close ties or family, moreover, he had little to lose, and a great deal to gain if he succeeded. For on one thing everyone was agreed. Hayward was a first-rate explorer and a surveyor of great skill. If he did get back alive, his discoveries were likely to be of immense value.

Originally, like his Kashgar journey, the Pamir expedition was to have been sponsored by the Royal Geographical Society, which now had Sir Henry Rawlinson as its President, and some of whose operations in Central Asia smacked as much of the Great Game as of geography. But in the meantime something had happened which had caused Hayward reluctantly to distance himself from the Society for fear of embarrassing it. It had also greatly increased the dangers of the expedition, for it had made an enemy of the Maharajah of Kashmir, through whose territory the explorer would have to pass on his journey northwards. The affair had sprung from an earlier visit which Hayward had made to a remote region beyond the Maharajah’s domains known as Dardistan. Here lived the Dards, a fiercely independent people with whom the Maharajah was constantly at war. It was from them that Hayward had learned of an appalling series of atrocities which Kashmiri troops had carried out in the Yasin area of Dardistan some years earlier. Details of these, which had included tossing babies into the air and cutting them in half as they fell, had been sent by Hayward to the editor of

The Pioneer,

the Calcutta newspaper. They had been published in full, under Hayward’s name, although he insisted that this had been done expressly against his instructions. Inevitably, a copy of the paper had found its way into the hands of the Maharajah, a ruler whose goodwill and cooperation the British authorities were most anxious to preserve, and who was now reported to be extremely displeased.

Even Hayward could hardly fail to see that this affair, and his own involvement in it, was highly embarrassing to both the British government and the Royal Geographical Society. He therefore wrote to the latter formally severing all connections with it for the duration of the expedition. The anger at the Maharajah’s court, he declared, ‘is very great, and it cannot be doubted that they will in every way secretly strive to do me harm’. Although he had been strongly advised to postpone or abandon his venture, he was nonetheless determined to proceed, despite the greatly increased risk. The fact that the matter was now public knowledge, he argued, would make it difficult for the Kashmiri ruler to harm him. Indeed, it might even oblige him to protect the party during its passage through his domains, lest he be blamed for any harm which befell it. Hayward made it clear, however, that the expedition was being undertaken entirely at his own risk and on his own decision. He hoped to reach Yasin, he said, in twenty-two days, and from there to enter the Pamir region by the Darkot Pass.

At the very last minute the Viceroy, Lord Mayo, had tried to persuade him to change his mind, warning him: ‘If you still resolve on prosecuting your journey it must be clearly understood that you do so on your own responsibility.’ But Hayward had already defied officialdom once by visiting Kashgar, and ultimately there was little that anyone could do to stop him this time. After all, he was not a government official, and was now no longer answerable to the Royal Geographical Society. He was a free agent. Undeterred therefore, and accompanied by five native servants, he set out northwards across the Maharajah’s territories in the summer of 1870. Travelling via Srinagar, his capital, and the small town of Gilgit, on Kashmir’s northern frontier, the party passed without incident into Dardistan. By crossing the no-man’s-land separating these two warring peoples, they had risked incurring the suspicions of both. Nonetheless, on July 13, they rode safely into Yasin, where they were warmly greeted by the local Dard chief, Mir Wali, whom Hayward knew from his earlier visit and believed to be his friend.

The true story of what ensued in this wild and desolate spot, where human life counted for little, will never be known. But during his brief halt in Yasin it seems that Hayward quarrelled with his host over which route he should take out of Dard territory into the Pamirs. Mir Wali, it is said, had been ordered by his own chief, the ruler of Chitral, to send Hayward to see him before being allowed to continue on his journey. But Hayward, already delayed, was anxious to press on. To travel to Chitral would have meant a considerable detour westwards, and anyway he was suspicious of the ruler’s motives. He thus refused, and an angry scene is said to have followed, during which the Englishman called Mir Wali by what was described as ‘a hard name’ in public. Other accounts challenge this, claiming that it was invented as an excuse for what was being planned. What is certain is that Hayward was bearing a number of highly desirable gifts which were intended for the chiefs of areas through which he had still to pass. These, according to several subsequent witnesses, had attracted the covetous gaze of Mir Wali, and possibly the ruler of Chitral, who were loath to see them leave their domains.

By now Mir Wali had abandoned his efforts to re-route Hayward via Chitral, even lending him coolies to see his party as far as the village of Darkot, twenty miles to the north, which marked the limits of his own territory. After an outwardly friendly parting from Mir Wali, Hayward left Yasin for Darkot, arriving there on the afternoon of July 17, and setting up his camp on a nearby hillside, 9,000 feet above sea level. Hayward, who had performed a great service for the Dards by exposing the Kashmiri atrocities, had no reason at that point to suspect treachery. However, that evening he was surprised to learn that a party of Mir Wali’s men had arrived unexpectedly in Darkot. They told the villagers that they had been sent to see the Englishman safely over the Darkot Pass on the following day. It seems, though, that they made no attempt to contact him. Hayward was puzzled by this, for he was not expecting the men, and Mir Wali had not mentioned them at their parting.

Something else worried him too. One of his servants now confided to him that shortly before they left Yasin an attempt had been made by Mir Wali to persuade him to desert. Hayward decided to take no chances. He would sit up all night, in case treachery was afoot. ‘That night,’ the village headman reported later, ‘the Sahib did not eat any dinner, but only drank tea.’ He sat alone in his tent, writing by the light of a candle. On the table before him were his firearms, loaded and ready. In his left hand he held a pistol, while he wrote with the other. But the night passed quietly. At first light everything appeared normal. Nothing stirred in the camp. Perhaps he had been worrying needlessly. Hayward rose and made himself some tea. Then, exhausted by the long night’s vigil, he fell asleep.

This was the moment Mir Wali’s men had been waiting for. One of them crept silently into the camp from the nearby undergrowth, where he and his accomplices had been hiding. He asked Hayward’s unsuspecting cook whether his master was asleep. On discovering that he was, he made for his tent. One of Hayward’s servants, a Pathan, spotted him and tried to stop him, but the rest of Mir Wali’s men now rushed in. The struggle was over in seconds. Hayward’s servants were all seized, and he himself pinioned while a noose was slipped around his neck. He had no time to reach for his firearms. Their arms tightly bound, the captives were next led into the forest. According to the headman’s account, which he obtained from the men themselves, Hayward tried to bargain with them for his own and his servants’ lives. First he offered them the contents of his baggage, including the gifts he was carrying, but they pointed out that these were already theirs for the taking. He next offered them substantial rewards of money which his friends would provide in exchange for the party’s release. However, the men clearly had their orders and showed no interest.