The Great War for Civilisation (65 page)

Like the sudden meeting with the young Lebanese man in Douai, the Middle East reaches out again. The fear of an Algerianâof his country, of his governmentâis present in this cheap hotel lobby in Paris. The killing of a soldier here more than eighty years ago is a safer subject. I translate Wills's testimony for Safian. He cannot understand why Wills shot Corporal Webster when he would have received a lesser charge for desertion. I climb the stairs twice. It only takes fifteen seconds to reach the second floor. When I run up the staircase, I reach it in five secondsâthe length of time it must have taken Corporal Webster. Wills would have had no time to conceal his gunâif he intended to. The second floor is only 5 metres square. Here Frank Wills struggled with Webster and left him lying in his blood on the floor. I walk into Room 22, nearest the stairs, Wills's room, the last place he slept in freedom before his death. Here he kept his great coat and his service revolver. He had been drinking on the morning of 12 March 1919, probably in this room. Punch, cognac and “American grog,” he had told the court. There had been an American soldier staying in the hotel who fled after the shooting. No one ever found out his identity. Was there an army mafia at work here? Who was running the gambling dens, providing the drinks? Who gave Wills the money he was found to be carryingâ6,640 French francs in notes and ten gold Louis coins?

I sit on my bed in Wills's room and read again through his testimony, this young man whom my father was ordered to kill, his last words written to spare his life.

I am 20 years of age. I joined the Australian Army in 1915 when I was 16 years of age. I went to Egypt and the Dardanelles. I have been in a considerable number of engagements there, & in France. I joined the British Army in April 1918 and came to France in June 1918. I was discharged from the Australian Army on account of fever which affected my head contracted in Egypt. I was persuaded to leave my unit by my friends and got into bad company. I began to drink and gamble heavily. I had no intention whatever of committing the offences for which I am now before the Court . . . I ask the Court to take into consideration my youth and to give me a chance of leading an upright and straightforward life in the future.

I could see how this must have affected Bill Fisk. Wills was not only the same ageâhe had been sent to France only two months before Bill arrived on the Somme. Wills had not deserted in time of war. But he had killed a British military policeman. I remember how Bill believed in the law, justice, courts, magistrates, policemen.

I walk out of the Paris hotel into the soft summer night. To the left is the street in which the two military policemen asked Wills and his colleague for their papers. A little further is the street called “Rue Albert” in the British documentsâit is the Rue Albert Thomasâin which Wills was grabbed by the French gendarme and pushed into a taxi andâaccording to Willsâstruck by a bayonet. By then, he had forfeited his life.

The Court Martial summary states that Wills was “sentenced to suffer death”; he was taken to the British base at Le Havre on the French coast on 24 May. Bill was based there in May 1919âhe took two snapshots of the camp, one of them with a church-tower in the backgroundâand was present when Wills arrived. In the British archives, I had turned to the final record of his execution with something approaching fear. Bill had spoken of his refusal to command the firing party. I believed him then. But the journalist in me, the dark archivist that dwells in the soul of every investigative reporter, needed to check. I think that Bill's son needed to know that his father did not kill Frank Wills, to be sure, to be absolutely certain that this one great act was real.

And there was the single scrap of paper recording Wills's death. Shot by firing squad. “Sentence carried out 0414 hours 27th May,” it read. The signature of the officer commanding was not in my father's handwriting. The initials were “CRW.” A note added that “the execution was carried out in a proper and humane manner. Death was instantaneous.” Was it so? Is death really instantaneous? And what of Wills in those last minutes, in the seconds that ticked by between four o'clock and 4:14 a.m., how did a man of only twenty feel in those last moments, in the dark in northern France, perhaps with a breeze off the sea? Did Bill hear the shots that killed him? At least his conscience was clear.

Bill Fisk was born 106 years ago but still remains an enigma for me. Was the French woman with whom he picnicked a girl who might have made his life happy, who might have prevented him returning on the Boulogne boat to Liverpool eighty-six years ago, to his life of drudgery in the treasurer's office and his first, loveless marriage? Was she perhaps the real reason why he volunteered to stay on in France after the war?

The Great War destroyed the lives of the survivors as well as the dead. By chance, in the same Louvencourt cemetery close to Bill's old billet lies the grave of Roland Leighton, the young soldier whose grief-stricken fiancée, Vera Brittain, was to write

Testament of Youth

, that literary monument to human loss. Perhaps the war gave my father the opportunity to exercise his freedom in a way he never experienced again, an independence that society cruelly betrayed. His medals, when I inherited them, included a Defence medal for 1940, an MBE and an OBE for postwar National Savings work, and two medals from the Great War. On one of them are the dates 1914â1919, marking not the Armistice of November 1918, but the 1919 Versailles Treaty which formally ended the conflict and then spread its bloody effect across the Middle East. This is the medal that bears the legend “The Great War for Civilisation.”

In Peggy's last hours in 1998, one of her nurses told me that squirrels had got into the loft of her home and destroyed some family photographs. I climbed into the roof to find that, although a few old pictures were missing, the tin box containing my father's Great War snapshots was safe. But as I turned to leave, I caught my head a tremendous blow on a roof-beam. Blood poured down my face and I remember thinking that it was Bill's fault. I remember cursing his name. I had scarcely cleaned the wound when, two hours later, my mother died. And in the weeks that followed, a strange thing happened; a scar and a small dent formed on my foreheadâidentical to the scar my father bore from the Chinese man's knife.

From the afterlife, Bill had tried to make amends. Amid the coldness I still feel towards him, I cannot bring myself to ignore the letter he left for me, to be read after his death. “My dear Fellah,” he wrote:

I just want to say two things to you old boy. Firstâthank you for bringing such love, joy and pride to Mum and me. We are, indeed, most fortunate parents. SecondâI know you will take the greatest possible care of Mum, who is the kindest and best woman in the world, as you know, and who has given me the happiest period of my life with her continuous and never failing love. With a father's affectionâKing Billy.

CHAPTER TEN

The First Holocaust

Pile the bodies high at Austerlitz and Waterloo.

Shovel them under and let me workâ

I am the grass; I cover all.

And pile them high at Gettysburg

And pile them high at Ypres and Verdun.

Shovel them under and let me work.

Two years, ten years, and passengers ask the conductor:

What place is this?

Where are we now?

I am the grass.

Let me work.

âCarl Sandburg, “Grass”

THE HILL OF MARGADA is steep and littered with volcanic stones, a place of piercing bright light and shadows high above the eastern Syrian desert. It is cold on the summit and the winter rains have cut fissures into the mud between the rocks, brown canyons of earth that creep down to the base of the hill. Far below, the waters of the Habur slink between grey, treeless banks, twisting through dark sand dunes, a river of black secrets. You do not need to know what happened at Margada to find something evil in this place. Like the forests of eastern Poland, the hill of Margada is a place of eradicated memory, although the local Syrian police constable, a man of bright cheeks and generous moustache, had heard that something terrible happened here long before he was born.

It was

The Independent

's photographer, Isabel Ellsen, who found the dreadful evidence. Climbing down the crack cut into the hill by the rain, she brushed her hand against the brown earth and found herself looking at a skull, its cranium dark brown, its teeth still shiny. To its left a backbone protruded through the mud. When I scraped away the earth on the other side of the crevasse, an entire skeleton was revealed, and then another, and a third, so closely packed that the bones had become tangled among each other. Every few inches of mud would reveal a femur, a skull, a set of teeth, fibula and sockets, squeezed together, as tightly packed as they had been on the day they died in terror in 1915, roped together to drown in their thousands.

Exposed to the air, the bones became soft and claylike and flaked away in our hands, the last mortal remains of an entire race of people disappearing as swiftly as their Turkish oppressors would have wished us to forget them. As many as 50,000 Armenians were murdered in this little killing field, and it took a minute or two before Ellsen and I fully comprehended that we were standing in a mass grave. For Margada and the Syrian desert around itâlike thousands of villages in what was Turkish Armeniaâare the Auschwitz of the Armenian people, the place of the world's first, forgotten, Holocaust.

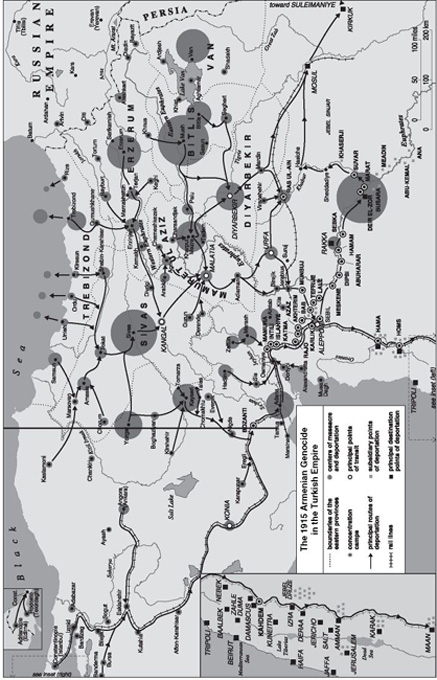

The parallel with Auschwitz is no idle one. Turkey's reign of terror against the Armenian people was an attempt to destroy the Armenian race. The Armenian death toll was almost a million and a half. While the Turks spoke publicly of the need to “resettle” their Armenian populationâas the Germans were to speak later of the Jews of Europeâthe true intentions of the Turkish government were quite specific. On 15 September 1915, for exampleâand a carbon of this document existsâthe Turkish interior minister, Talaat Pasha, cabled an instruction to his prefect in Aleppo. “You have already been informed that the Government . . . has decided to destroy completely all the indicated persons living in Turkey . . . Their existence must be terminated, however tragic the measures taken may be, and no regard must be paid to either age or sex, or to any scruples of conscience.”

Was this not exactly what Himmler told his SS murderers in 1941? Here on the hill of Margada, we were now standing among what was left of the “indicated persons.” And Boghos Dakessian, who along with his five-year-old nephew Hagop had driven up to the Habur with us from the Syrian town of Deir es-Zour, knew all about those “tragic measures.” “The Turks brought whole families up here to kill them. It went on for days. They would tie them together in lines, men, children, women, most of them starving and sick, many naked. Then they would push them off the hill into the river and shoot one of them. The dead body would then carry the others down and drown them. It was cheap that way. It cost only one bullet.”

Dakessian knelt beside the small ravine and, with a car key, gently prised the earth from another skull. If this seems morbid, even obscene, it must be remembered that the Armenian people have lived with this for nine decadesâand that the evidence of evil outweighs sensitivity. When he had scraped the earth from the eye sockets and the teeth, Dakessian handed the skull to little Hagop, who stood in the ditch, smiling, unaware of the meaning of death. “I have told him what happened here,” Dakessian says. “He must learn to understand.” Hagop was named after his great-grandfatherâBoghos Dakessian's grandfatherâwho was himself a victim of the first Holocaust of the twentieth century, beheaded by a Turkish gendarme in the town of Marash in 1915.

In Beirut back in 1992, in the Armenian home for the blindâwhere the last survivors had lived with their memories through the agony of Lebanon's sixteen-year civil war, I would discover Zakar Berberian, in a room devoid of light, a single electric bar vainly struggling with the frosty interior. The eighty-nine-year-old Armenian cowered in an old coat, staring intently at his visitors with sightless eyes. Within ten years Zakar Berberianâlike almost all those who gave me their testimony of genocideâwas dead. But here is his story, just as he told it to me:

I was twelve years old in 1915 and lived in Balajik on the Euphrates. I had four brothers. My father was a barber. What I saw on the day the Turkish gendarmes came to our village I will never forget. I had not yet lost my eyesight. There was a market place in Balajik which had been burned down and there were stones and building bricks on the ground. I saw with my own eyes what happened. The men were ordered to leave the villageâthey were taken away and never seen again. The women and children were told to go to the old market. The soldiers came then and in front of the mothers, they picked up each childâmaybe the child was six or seven or eightâand they threw them up in the air and let them drop on the old stones. If they survived, the Turkish soldiers picked them up again by their feet and beat their brains out on the stones. They did all this, you see? In front of their mothers. I have never heard such screaming . . . From our barber's shop, I saw all these scenes. The Turkish soldiers were in uniform and they had the gendarmerie of the government with them. Of course, the mothers could do nothing when their children were killed like this. They just shouted and cried. One of the children was in our school. They found his school book in his pocket which showed he had the highest marks in class. They beat his brains out. The Turks tied one of my friends by his feet to the tail of a horse and dragged him out of the village until he died.

There was a Turkish officer who used to come to our shop. He sheltered my brother who had deserted from the army but he said we must all flee, so we left Balajik for the town of Asma. We survived then because my father changed his religion. He agreed to become a Muslim. But both my father and my mother got sick. I think it was cholera. They died and I was also sick and like a dead person. The deportations went on and I should have died but a Turk gave me food to survive.

Berberian was eventually taken to a children's orphanage.

They gave me a bath but the water was dirty. There had been children in the same bath who had glaucoma. So I bathed in the water and I too went blind. I have seen nothing since. I have waited ever since for my sight to be given back to me. But I know why I went blind. It was not the bath. It was because my father changed his religion. God took his revenge on me because we forsook him.

Perhaps it was because of his age that Berberian betrayed no emotion in his voice. He would never see again. His eyes were missing, a pale green skin covering what should have been his pupils.

So terrible was the year 1915 in the Armenian lands of Turkey and in the deserts of northern Syria and so cruel were the Turkish authorities of the time that it is necessary to remember that Muslims sometimes risked their lives for the doomed Armenian Christians. In almost every interview I conducted with the elderly, blind Armenians who survived their people's genocide, there were stories of individual Turks who, driven by religion or common humanity, disobeyed the quasi-fascist laws of the Young Turk rulers in Constantinople and sheltered Armenians in their homes, treating Armenian Christian orphans as members of their own Muslim families. The Turkish governor of Deir es-Zour, Ali Suad Bey, was so kind to the Armenian refugeesâhe set up orphanages for the childrenâthat he was recalled to Constantinople and replaced by Zeki Bey, who turned the town into a concentration camp.

The story of the Armenian genocide is one of almost unrelieved horror at the hands of Turkish soldiers and policemen who enthusiastically carried out their government's orders to exterminate a race of Christian people in the Middle East. In 1915, Ottoman Turkey was at war with the Allies and claimed that its Armenian populationâalready subjected to persecution in the 1894â96 massacresâwas supporting Turkey's Christian enemies. At least 200,000 Armenians from Russian Armenia were indeed fighting in the Tsarist army. In Beirut, Levon Isahakianâ blind but alert at an incredible 105 years oldâstill bore the scar of a German cavalry sabre on his head, received when he was a Tsarist infantryman in Poland in 1915. In the chaos of the Bolshevik revolution two years later, he made his way home; he trudged across Russia on foot to Nagorno-Karabakh, sought refuge in Iran, was imprisoned by the British in Baghdad and finally walked all the way to Aleppo, where he found the starving remnants of his own Armenian people. He had been spared. But thousands of Armenians had also been serving in the Ottoman forces; they would not be so lucky. The Turks alleged that Armenians had given assistance to Allied naval fleets in the Mediterranean, although no proof of this was ever produced.

The reality was that a Young Turk movementâofficially the “Committee of Union and Progress”âhad effectively taken control of the corrupt Ottoman empire from Sultan Abdul Hamid. Originally a liberal party to which many Armenians gave their support, it acquired a nationalistic, racist, pan-Turkic creed which espoused a Turkish-speaking Muslim nation stretching from Ankara to Bakuâa dream that was briefly achieved in 1918 but which is today physically prevented only by the existence of the post-Soviet Armenian republic. The Christian Armenians of Asia Minor, a mixture of Persian, Roman and Byzantine blood, swiftly became disillusioned with the new rulers of the Turkish empire.

70

Encouraged by their victory over the Allies at the Dardanelles, the Turks fell upon the Armenians with the same fury as the Nazis were to turn upon the Jews of Europe two decades later. Aware of his own disastrous role in the Allied campaign against Turkey, Winston Churchill was to write in

The Aftermathâ

a volume almost as forgotten today as the Armenians themselvesâthat “it may well be that the British attack on the Gallipoli Peninsula stimulated the merciless fury of the Turkish government.” Certainly, the Turkish victory at the Dardanelles over the British and Australian armiesâPrivate Charles Dickens, who peeled Maude's proclamation from the wall in Baghdad, was there, and so was Frank Wills, the man my father refused to execute in 1919âgave a new and ruthless self-confidence to the Turkish regime. It chose 24 April 1915âfor ever afterwards commemorated as the day of Armenian genocideâto arrest and murder all the leading Armenian intellectuals of Constantinople. They followed this pogrom with the wholesale and systematic destruction of the Armenian race in Turkey.

Armenian soldiers in the Ottoman army had already been disbanded and converted into labour battalions by the spring of 1915. In the Armenian home for the blind in Beirut, ninety-one-year-old Nevart Srourian held out a photograph of her father, a magnificent, handsome man in a Turkish army uniform. Nevart was almost deaf when I met her in 1992. “My father was a wonderful man, very intelligent,” she shouted at me in a high-pitched voice. “When the Turks came for our family in 1915, he put his old uniform back on and my mother sewed on badges to pretend he had high rank. He wore the four medals he had won as a soldier. Dressed like this, he took us all to the railway station at Konya and put us on a train and we were saved. But he stayed behind. The Turks discovered what he had done. They executed him.”

In every town and village, all Armenian men were led away by the police, executed by firing squad and thrown into mass graves or rivers. Mayreni Kaloustian was eighty-eight when I met her, a frail creature with her head tied in a cloth, who physically shook as she told her story in the Beirut blind home, an account of such pathos that one of the young Armenian nursing staff broke down in tears as she listened to it.

I come from Mush. When the snow melted each year, we planted rye. My father, Manouk Tarouian, and my brother worked in the fields. Then the Turkish soldiers came. It was 1915. They put all the men from the village, about a thousand, in a stable and next morning they took them from Mushâall my male relatives, my cousins and brothers. My father was among them. The Turks said: “The government needs you.” They took them like cattle. We don't know where they took them. We saw them go. Everybody was in a kind of shock. My mother Khatoun found out what happened. There was a place near Mush where three rivers come together and pass under one bridge. It is a huge place of water and sand. My mother went there in the morning and saw hundreds of our men lined up on the bridge, face to face. Then the soldiers shot at them from both sides. She said the Armenians “fell on top of each other like straw.” The Turks took the clothes and valuables off the bodies and then they took the bodies by the hands and feet and threw them into the water. All day they lined up the men from Mush like this and it went on until nightfall. When my mother returned to us, she said: “We should return to the river and throw ourselves in.”