The Greek Islands (23 page)

Authors: Lawrence Durrell

Pacing the battlements of the monastery, you can enjoy a splendid view of the whole island, and also catch a glimpse of sinister Mount Cerceteus lying to the north like a watchful hammer-head shark. It seems to attract electrical storms, and the frequent displays of fireworks have given rise to a number of legends in the island itself, where the peasants call it St John's Light. I have tried to find a concrete side to this rather odd ascription â perhaps a folk-tale or a legend which would explain what the devil (

sic

) St John might have had to do with electrical storms on the faraway mountain â but have had no success. The peasant woman I asked could not answer my

question

, but it certainly did not trouble her; she simply shrugged her shoulders and went on beating an octopus against the rocks of Scala, in order to soften it up for lunch. The real treasure of Patmos is the great library, and this is what makes it worthwhile to mount a mule and go wobbling up the precipitous road to the monastery; this and of course the views.

The great library is now no more than a shadow of its former self. Diligent âcollectors' across a couple of centuries have stolen or borrowed priceless things, which have later turned up in the national libraries of Germany, France and England. The same argument which is trotted out to excuse the affair of the Elgin Marbles is in order here â namely, that local ignorance and neglect constituted a greater danger to the manuscripts than their pilfering for a market which at least preserved the spoils of

these forays. There would, say we, have

been

no Elgin Marbles to squabble over had Elgin not bought them â for the local Greak apathy was exceeded only by Turkish neglect. And now that the Acropolis itself is melting away, a victim of the petrol engine, what is one to think? Myself, I think I should have given them back and kept copies of them in plaster for the British Museum. For us, they are a mere possession of great historic interest. For the Greeks they are a symbol, inextricably bound up with their national struggle not only against the Turks, but also against an image of themselves as bastard descendants of foreign tribes (not Greeks at all); an image which they very successfully shattered during the Albanian campaign, thus

putting

modern Greece squarely on the world maps as the right true heir to the Periclean heritage. Their simple âNo' to Mussolini was as perfect as any Periclean declaration.

In the catalogue of the Patmos library, some six hundred manuscripts are recorded; but now only two hundred and forty are left to admire. The most valuable, and at the same time the most charming to the eye, is the celebrated Codex Porphyrius of the fifth century, of which the major portion is still in Russia. The Orthodox Church has always had strong links with the Balkans, though there are now only a few monasteries left which were originally populated by Russian monks for whom Mount Athos was always a place of holy pilgrimage. The

absoluteness

of this strange peninsula, where no female creature (neither woman nor hen) is welcome, mark it out as an uncompromising forcing-house for monks disposed to

mysticism.

Mind you, laymen with a religious turn of mind often arrange to take a retreat in an Athos monastery, in order to purge their souls of the material dross of everyday life. The two poets, Kazanzakis and Sikelianos, came here together and spent over a year in prayer and meditation â a period of religious striving about which Kazanzakis has left us a moving testimony.

His mind was divided between, on the one hand, the

spontaneous

old rogue Zorba, exulting in life, and on the other, the problems of St Paul and St Francis, which he found so

tormenting.

His work spans the full spectrum of the Greek soul, which is highly sceptical and irreverent, and at the same time

profoundly

religious, though only in the anthropological sense. I recall a diplomat telling me once that whenever he travelled with Vichinsky to the United Nations, the old Russian Communist delegate never failed to cross himself in the Byzantine style before taking a plane. It is wise to take such precautions. One never knows.

And so northward in the direction of Samos, but with a

stopover

at the unrewarding and rugged Icaria which has an unkempt air, as if it has never been loved by any of its

inhabitants

. This is understandable; it won't bear comparison with its magnetic neighbours, and moreover, it lies awkwardly abaft the channel, as if the first intention was to be a stopper of it. All that its position achieves is interference with the free-running tides from north to south, creating the sort of lee which is not

sufficiently

interesting for people under sail. The impression it gives of disorder and vacillating purpose is increased by a visit ashore â the road system has the air of being thought up by a drunken postman. There are some thermal springs, but they do not enjoy great renown. To write more about Icaria would be like trying to write the Lord's Prayer on a penny. Onward then to the spacious bays of Marathocampus in Samos, and the grizzled head of Mount Cerceteus.

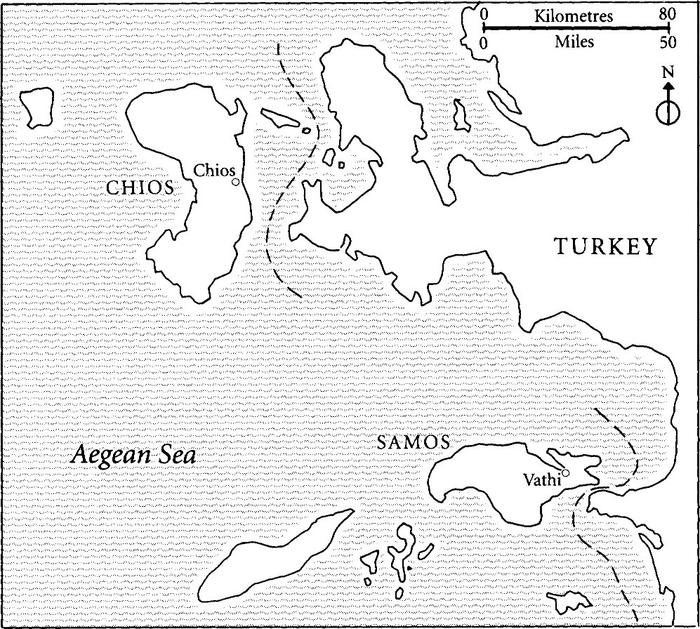

There is some justification for linking these two islands together; they are equally important historically, and both share the proximity of the Turkish mainland which in ancient times must have given them a distinct metropolitan flavour. Samos is separated from the mainland by a small gap hardly two

kilometres

in length. To me, the approach to this famous island is more beautiful than the island itself. You travel, by magnificent sea-roads, as if across the heart of some fine old Victorian

steel-engraving

by Lear or Landseer, among headlands and

promontories

of unstudied grandeur, which the Victorian traveller always described as ‘sublime’. It is sublime. After this approach, the island itself, despite its harsh backbone of mountain,

despite

the grizzled head of Mount Cerceteus which lifts itself up to nearly 5000 feet (1520 m), is a little disappointing.

Chios, twenty miles away, boasts of Homer, while Samos can only put up one tyrant of genius and a mathematician called Aristarchus – who has no right to be as little known as he is, for, after all, his heliocentric notions of the heavens anticipated Copernicus by some two thousand years. Fertility was the essence of classical Samos, and provided it with even more nicknames than Rhodes. Homer alludes to the island as watery, but he was outdone by other Samiot enthusiasts, who called it

Anthemis

for its flowers,

Phylis

for its greenery,

Pityoussa

for its pines,

Dryoussa

for its oaks, and so on. Indeed people were so carried away by the greenness and abundance of Samos that Menander, the poet, announced that the fowls in this Eden

produced not only eggs but milk as well. Perhaps he was

parodying

the extravagance of Samiot claims? I saw very few fowls (and found the food calamitous) when I spent a weekend in Vathi, the main harbour, which is a colourful enough little place but awkwardly sited for the frequent winds, that scatter spray and dust with equal abandon. The second harbour, Tigani (Frypan), is more attractive; spacious and eloquent itself, it has fine views of the Turkish mountains which hover down to Cape Kanapitza. There are several little taverns with good seafood, and here, if you wish to pander to local patriotism, you may ask for a performance of the loveliest Greek folk song of all,

Samiotissa

(‘Samiot girl’), and use its stately, lilting measure to learn the finest and gravest of the Greek dances, the

Kalamatiano

.

It is singular that, in an island so famous for its sculpture, artificers in precious metals, and carvers, the names of few

eminent

individuals have descended to today. Polycrates the tyrant, who made Samos queen of the seas in 535

BC

, has hogged the stage of history.

The reputation of Polycrates is not undeserved for, apart from his conquests on land and sea, he was also a

discriminating

patron of the arts, who invited many distinguished poets to visit his island court. His rise to fame was staggering in its swiftness, and at the height of his power he had a fleet of galleys of one hundred and fifty oars and an army of a thousand

bowmen

on call. At heart he remained a corsair, and his maraudings seem to have been unplanned and without any central object. He went to war for the fun of it; yet, magically, was always the winner. He inspired a small vignette by Herodotus, on which his fame still largely rests. In order to escape the jealousy of the gods, he threw a rich emerald ring into the sea; but after a day or two a fisherman turned up at the court with a huge fish for dinner. When it was carved, the ring was found inside. ‘A sure sign’, says the historian, ‘(for a man so lucky that even what he

had thrown away came back to him) that he would die a

miserable

death.’ Which he indeed did, for he finally allowed himself to be lured into Ionia and arrested by his enemies, who revenged themselves on his past misdeeds by flaying and crucifying him.

It was under Polycrates’s rough rule that three of the greatest engineering feats of the ancient Greek world were carried out. The first was the great mole which protects the harbour;

Lesbian

slaves were forced to fashion this as a punishment for taking arms against the Samiots. The second was the

extraordinary

tunnel which exists even to this day as a water-conduit for the capital. The third was the temple of Hera which was one of the wonders of the ancient world, and of which little now remains except the site, starkly beautiful on its headland where goats browse and untiring eagles weave overhead. Cape Colonna, as the place is called, has priceless views of the mainland from every spur; but of Hera’s temple only a single column marked the spot when last I was there.

The tunnel which brought the water to the ancient town is certainly a fantastic feat of engineering, for its time. About a mile long, eight feet wide and eight high, it is still negotiable for most of its length. Some sections in the middle have caved in, but I was told that, with the help of a torch, one could still get through quite easily. I went halfway along it many years ago, to where there is a tiny Byzantine chapel, in which, mysteriously enough, the oil in the lamp seemed to be freshly poured. I wondered what sort of zealot or sacristan snaked down the dark tunnel to perform this votive act. It is something I have

wondered

many times in Greece. There are numerous remote,

deserted

chapels or hermitages, either on the tops of mountains as in Crete, or on the seashore surrounded by high cliffs so that they can only be reached by sea; yet I have hardly come upon one, however remote, which had not been recently dusted, and

the oil in the altar lamps replenished by invisible hands. Little pagan wayside shrines keep you heart-whole in the Greek countryside; my own pet shrine to St Arsenius in Corfu is entirely cut off from the land by high cliffs, but it is always tended – one might suppose by spirits, for I have never glimpsed the tender. However, other shrines are modest in comparison with the temple built for the prayers of the tyrant; for Polycrates, nothing but the best would do. The original temple boasted 134 Ionic columns, and when it was burned down its successor was even larger. This gorgeous monument had the merit of affording work to the best sculptors and

architects

of the day, and doubtless deserved its ancient reputation as the finest thing achieved in the ancient world.

Because of its richness and ambiguous position, Samos has always been a pawn in the game of international politics, from the time the Spartans landed (and were soon replaced by Athenians), onwards. As a Roman province, she enjoyed a short period of stability and happiness, since Augustus liked the place and accorded it his favours. Then, still in Roman times, Antony sacked it. This cocktail-party playboy chose Samos for one of his greatest displays, a mammoth party, at which he was ably assisted by Cleopatra, and to which the whole civilized world was bidden; the feasting and debauchery went on for months. This was Antony’s way of starting a war – a kind of preliminary flourish, so to speak.

As for the famous Samian wine – find it who can, in the island of its birth. I suspect that one would have to know one of the great families of the island to taste it; the taverns do not have anything to justify its reputation. Yet it exists, that foaming cup that Byron was always ‘dashing down’ in a fever of

petulance

because Greece was not free. I have drunk it in several private houses in Athens, notably in that of the Colossus of Maroussi, who has it specially sent over the water (and from

whose vinous disquisitions I have learned much of what I know about present-day Samos). There is also a Samos

mastika

, if you like anisette, which gives you the feeling of having been caught up in a combine-harvester and bundled out as trussed straw.

There is goodish upland-shooting in Samos during the

winter

months, and its wildness is commended by campers and walkers. You feel the wildness of Asia Minor in the air, and in the hazy distances sense the obscure, nomadic tribes on the mainland across the way, where huge and grumpy mountains lie like sofas out of work.

Chios is very different, though its size and geographical position are similar. The impression of desuetude is quite marked in the little capital town, and I think that earthquakes have been responsible for overturning its more precious architectural glories. A feeling of past luxuriance remains – smothered in dusty gardens full of oranges, lemons,

pomegranates

, flowering judases and cypresses; but the town has the kind of seediness that comes from business dealings. Yet it is a rich little island, which exports fruit, cheese and jams to Athens, and has made a speciality of the juice of the mastic plant which, according to the pious historians of hard liquor, was a gift from St Isidore – though what a self-respecting saint like Isidore was doing so far from his home territory in Salonika (his church is a treasure) I cannot tell.

The story of modern Chios is the story of this mastic plant. It is a plant that grows all over the Mediterranean, but only the Chiots have specialized in its cultivation, and developed it on a large scale. In addition to the drink, there is a pleasant white chewing-gum with a delicious flavour made from the plant. This has always been in great demand in the Turkish harems, since it combines the qualities of breath-sweetener and

ordinary

chewing-gum with helpful digestive and tranquillizing qualities. The plant is a relatively common one –

Pistacia

lentiscus

– and one is surprised on looking it up in the

encyclopedia

to read: ‘The production of the mastic has been, from the time of Dioscorides, almost exclusively confined to the island of Chios.’ One suspects that the first big market for mastic was the seraglio, for at one time the whole trade passed into Turkish hands, and was re-financed. When I first reached Athens in 1935, the little tablets of mastic were in common use, but as time went on they were replaced by American chewing-gum which, though less refreshing, was considered more

chic

by the Athenians.

If the capital is somewhat depressing, one can find much to admire in the extraordinary green plain called the Campos, which is the source of the island’s present-day wealth. It lies some way from the town; and here the holdings and country houses of the rich families have congregated, to form an ensemble of great charm and originality which is, as far as I know, unique among the islands, even among the greenest such as Rhodes and Corfu. It is a romantic place, of shuttered

gardens

defended by great wrought-iron gates half-rusted black, and with tangled groves of citrus and olive stretching away up into the sky. And, like all such places, it is apparently tenantless. Empty houses, gardens without gardeners, weathercocks which do not turn on battered towers, dogs that crouch but do not speak. You can wander for hours in search of the Sleeping Beauty – so likely does it seem that she will be drowsing

somewhere

here – or else of Daphnis and Chloe, though it is not their island, strictly speaking.

The prevailing odour of dust and lemons and rock-honey is what you will most probably bring with you out of Chios. A more intrepid wanderer than myself, Ernle Bradford, has noted: ‘I can confirm that one can smell the citrus groves of Chios from the sea, specially if one arrives in the early morning, and there has been a dew-fall overnight. The fertile islands like

Samos, Corfu and Rhodes, to mention but three, all have a definable smell.’ But you are more likely to experience this under sail during one of those lagging summer calms when your boat lolls and sways towards your landfall, hardly moving. And even before the smell the far creaking of

cicadas

will come across the water to you, like rusty keys.

The mastic villages in the south of the island are

unremarkable

save for their cultivated bushes of the herb, some six feet high, like the new-style French olive-trees which are cropped low, in the manner of tea-bushes. Incisions in the body of the plant bleed the mastic juice. The drink is still going strong, and you can still find the chewing-gum, though the trade in it is no longer what it was. Of the ‘submarine’ – that absurdity invented by the cafés to thrill its youngest customers – I have written elsewhere; it consists of a spoonful of mastic confiture plunged into a glass of cold water. The name in Greek means ‘an Underwater Thing’ and you see a very ancient Greek expression on children’s faces as they suck the white jam from the spoon. They are obviously in Disneyland, aboard the big submarine which is one of the marvels of the American scene.

As for Homer … of the seven cities which have contended, in the words of the old epigram, the claims of Chios to be his birthplace are well founded if one notes the reference in the Homeric Hymns to ‘the blind old man of rocky Chios’. In the north of the island, Kardamyla is supposed to be where he was born. Why not? There is a block of stone called ‘The stone of Homer’ outside Chios town which is more likely to be an ancient menhir or something of the kind. It reminds the visitor of the big block of Agrigento marble thrown down in a field outside the village of Chaos in Sicily: where the ashes of the great Pirandello have been scattered.

Nearby is Pashavrisi – or Pashaspring – which is rapidly becoming a summer resort of consequence. Good beaches with

an eatable

taverna

to hand are not numerous in Chios unless you are adventurous and have time to cover a good distance by taxi. It is wise to use the taxi to visit the splendid monastery of Nea Moni, situated just below the crown of the mountain called Provatium. Splendour and isolation combine with a rich set of eleventh-century frescoes to make such a trip memorable. The frescoes were sadly jumbled by the great earthquake of 1881, though enough are still extant to provide a graphic notion of what they must once have been. With the new interest in

Byzantine

art as an aesthetic there is talk here, as elsewhere, of having them tactfully restored. The monastery has however fallen upon meagre days, and its once hundred-strong monkery is now reduced to a handful of lumbago-ridden mystics who are bored stiff with the scenery and the frescoes and are eager to have a chat with people from the outer world.