The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism (18 page)

Read The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism Online

Authors: Edward Baptist

Tags: #History, #United States, #General, #Social History, #Social Science, #Slavery

Image 2.1. Jackson’s victory at New Orleans in January 1815 was the capstone to twenty-five years of violence that ensured United States enslavers would control the Mississippi Valley. This illustration shows the way the swamps to the north and the river to the south constricted British options and forced them to attack Jackson’s cotton-bale-protected defenders across the muddy ground of a winter sugarcane field. “Battle of New Orleans,” Hyacinthe Laclotte, 1820. Library of Congress.

The elation was undiminished by the simultaneous arrival of the news, from Europe, that American negotiators had signed a peace treaty with Britain at the neutral city of Ghent on December 22, 1814, even as British troops disembarked from their ships at Lake Borgne. The terms of the treaty essentially

returned everything to the starting position of 1812, giving captured territory back to its owner. Some have claimed that the treaty rendered Jackson’s victory at New Orleans irrelevant, except for enshrining Jackson as a nationalist icon. But with the prize of the Louisiana Territory in their hands,

the British would have been entitled, according to their own interpretations, to hold onto it

or give it back to Spain. In fact, Article IX of the Treaty of Ghent obligated the United States to return land taken from Britain’s Indian allies—who included the Red Stick Creeks. Thanks to Jackson’s victory, however, the United States was in no position to feel compelled to reverse the Treaty of Fort Jackson and remand 36,000 square miles to Creek custody. So the Battle of New Orleans protected

the windfall the United States had caught when the sacrifices of the Haitian Revolution shook the tree of empire, and it confirmed Jackson’s great land grab from the Creeks as well. Slavery’s expansion could now proceed unchecked.

The man in the iron collar had come to slavery’s new frontier, a place created by violence. Revolution in Saint-Domingue overthrew the old pattern of early modern slavery,

which had driven one kind of economic development in the Atlantic world. Haiti’s revolutionaries had offered the world a radically new concept of human rights, the right of all to become equal citizens. But this vision did not become reality, either in independent Haiti or elsewhere. Indeed, the death of the old slavery cleared room for something quite different: a new, second slavery. Constructed

first in the southwestern United States, this modern and modernizing process brought benefits and rights to ever wider groups of people while stripping them, with great violence, ever more radically from others. At the Mississippi’s mouth, brutal force defended this infant process from the efforts of the enslaved to block it, marking the ramparts of its cradle with the severed heads of rebels.

Next, Jackson completed American possession of the southwestern frontier with victories that opened thousands of square miles. Now a continental empire was possible, one that had vast resources within its reach. But to create vast and sweeping dominions out of the chaos that their own violence amplified, the victors would still need many things: credit, land, markets, crops, authority, and hands—above

all, hands, hands to write, to buy, to reach, to grasp, to plant, and to harvest.

F

ROM THE DECK OF

the brig

Temperance

to the grass-clotted soil of the New Orleans levee stretched a long narrow plank. It bent under the weight of the four men as they filed across it, bent under Rachel’s, too, as she followed.

Throughout the morning of January 28, 1819, one white man after another had boarded, talked with Captain Beard, and walked back down

the gangplank. One had taken a couple of the brig’s twenty-four enslaved passengers. Rachel, standing by the deck rail in her new clothes, had watched them disappear between the huge piles of cotton bales on the levee.

The opposite deck rail had showed her the river. Hundreds of masts were in sight, seagoing brigs and barques and sloops and schooners moored along the levee like the

Temperance

. River flatboats by the hundred were here to unload their Ohio corn and hogs, Mississippi cotton, and Kentucky tobacco. She could see the stacks of a dozen steamboats. And working its way across the muscular brown chop of the Mississippi had come one little rowboat. A slight, black-suited white man sat upright in the stern. And a black man worked the oars.

1

Now, at the end of the plank, Rachel

put her feet on Louisiana. On unsteady legs she climbed the levee to the southwest. She’d been six weeks on the water since the

Temperance

had left Baltimore. That was where merchant David Anderson had purchased her for consignment to his New Orleans partner Hector McLean. Anderson had also bought William (tall, dark, age twenty-four), George, Ellis, and Ned Williams. Rachel now followed them

up the slope. Her head rose over the top of the levee. As she reached out to balance herself, her hand found a bare post driven into the dirt, one in a long series stretching upriver, each one separated from the next by a mile or so.

Nailed to it was, perhaps, a placard. Its words were everywhere in New Orleans: tacked to walls and posts, printed in directories and newspapers. “AT MASPERO’S COFFEE

HOUSE. . . . PETER MASPERO AUCTIONEER,

Informs his friends and the public that he continues to sell all kinds of

MERCHANDISE, REAL ESTATE, AND SLAVES . . .

in Chartres Street

.” And at the bottom: “

Looking-glass and Gilding Manufactory. P. Maspero

.”

2

From the levee, Rachel could see a city in the midst of full-tilt growth. Populated by 7,000 people at the time of American acquisition in 1803,

New Orleans now claimed 40,000. Already this was the fourth-largest city in the United States, behind New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. In commercial dynamism, Jefferson’s “one spot on Earth” was equaled only by New York. From every quarter hammers pounded on the ear, nailing timbers of broken-up flatboats together into storefronts. To the east, downriver of the

Temperance

’s mooring-point

at the French Quarter, stretched the Marigny district, a mostly French-speaking “Faubourg,” or suburb. To the west spread the rapidly growing “American Quarter,” or Faubourg St. Mary. As Rachel followed the others down the levee’s other slope, they passed a chain gang—“galley slaves,” New Orleans residents called them, slaves who for the crime of running away were locked in the dungeons behind the

Cabildo at night and brought out to build up the levee by day. The city government could punish resistance while simultaneously using rebellious slaves’ labor to protect the city from the giant river that crested each spring.

3

At the bottom of the levee, parallel to it, ran a dirt avenue—Levee Street—and as they stepped onto it the five entered a city whose vortex had been sucking at their feet

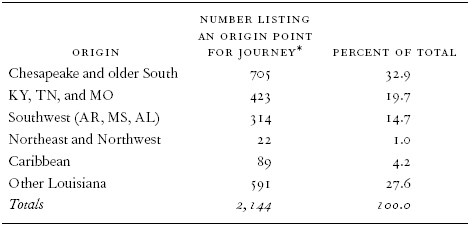

ever since Maryland. Here, women of every shade called out in French, English, Spanish, and Choctaw, selling food and trinkets, but beneath the patter was another hum, that of bigger business—and it was booming. On corners, under the awnings of new brick buildings, white men gathered, talking. Heads turned, appraising. Before the War of 1812, enslaved people from other US states had been relatively

scarce in New Orleans. But from 1815 to 1819, of those sold, about one-third were new arrivals from the southeast—Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina (see

Table 3.1

). Another 20 percent came down the river from Kentucky. A few hundred came from northern states such as New Jersey and Pennsylvania, slipped out in contravention of gradual emancipation laws that contained provisions designed to keep

masters from liquidating in a going-out-of-business sale.

4

One turn left, and they headed up a muddy street. In the middle: a ziggurat of cotton bales, taller than the men who muscled them up, too wide for carts to pass. It being January, the crop was coming down at full tide on

flatboats and steamers. Even as the employees of cotton dealers piled bales high, teamsters hired by cotton buyers

chipped them back down: pulling bales out, checking letters branded on cotton wrapping, hauling the 400-pound cubes of compressed fiber toward the river.

TABLE 3.1. SLAVES IMPORTED TO AND SOLD IN NEW ORLEANS, 1815–1819

Source:

Hall Database,

www.ibiblio.org/laslave/

.

*

The variable used was “Via,” which records the place from or by which the seller brought the slave to New Orleans; 6,698 other sales either contain no entry for this variable or record Orleans Parish.

If Rachel could’ve followed the bale, she’d have seen it loaded from the levee onto oceangoing vessels. These would carry the bales across the

Atlantic to Liverpool on England’s northwestern coast, where dockworkers moved the bales to warehouses. After sale on the Liverpool cotton market, they went by canal barge to Manchester’s new mills. Textile workers—often former operators of hand-powered looms, or displaced farmworkers—opened the bales. Using new machines, they spun the cleaned cotton fibers into thread. Using other machines, they

wove the thread into long pieces of cloth. Liverpool shipped the bolts of finished cloth, and they found their way into almost every city or town in the known world, including this one.

Cotton cloth was why New Orleans was booming, why the world was changing. White entrepreneurs here—like the customers in the shops Rachel was passing, the men on the corners, the sellers and buyers on the ships

along the levee—were participating in, even driving, this worldwide historical change. Building on the government-sponsored processes of migration and market-making taking place in Georgia, and the battles fought by the slaveholders’ military to open up the Mississippi Valley, after 1815 a new set of entrepreneurs had begun to use Rachel and all the others brought here against their wills to create

an unprecedented boom. It linked technological

revolutions in distant textile factories to technological revolutions in cotton fields, and it did so by combining the new opportunities with the financial tools needed to make economic growth happen more quickly than ever before. This boom was changing the world’s future, and these entrepreneurs who used Rachel were establishing themselves and their

kind as one of the most powerful groups in the modernizing Western world that cotton was making.