The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy (12 page)

Sketch 11 of storyboard for Birth of Frank reshoot.

Sketch 12 of storyboard for Birth of Frank reshoot.

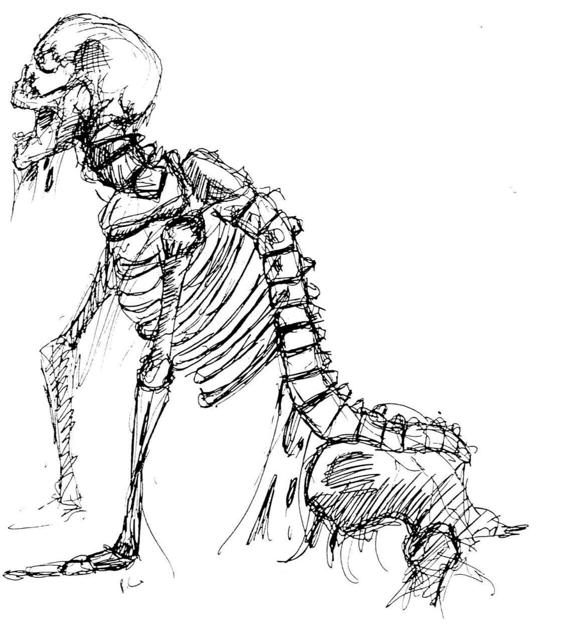

Sketch 13 of storyboard for Birth of Frank reshoot.

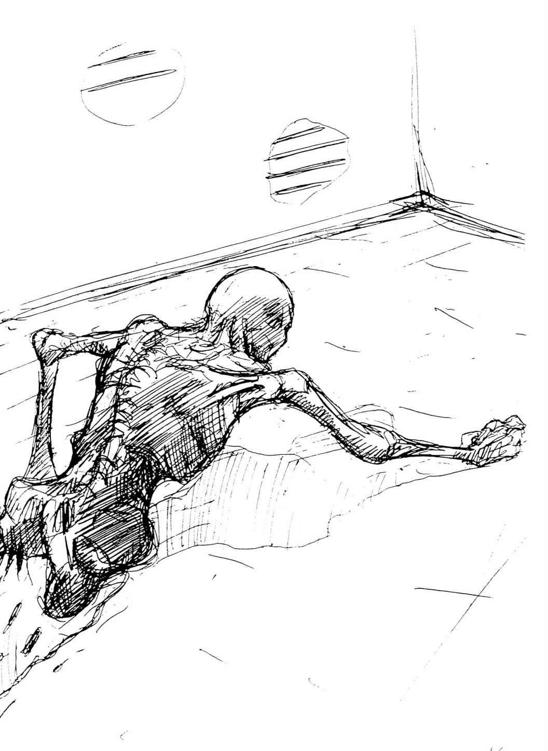

Sketch 14 of storyboard for Birth of Frank reshoot.

Barker has also quoted the playwright John Webster (c. 1578—1632) as being a strong influence on his work, especially regarding the depiction of violence and sensation. In plays such as

The White Devil

(c.1612) and

The Duchess of Malfi

(c.1614), we’re presented with the familiar themes of revenge, but we also have the unusual, such as a suitor fooled into kissing the poisoned lips of a dressed up skull, or hints of witchcraft and lycanthropy. “My favorite playwright of violence is Webster,” Barker has clarified. “He’s the grand master of the violent set-piece, in which there’s a broad configuration of events, circumstances, relationships, which are leading inevitably to some dire conclusion.”

5

Barker’s love of Harryhausen and special effects in general has already been noted, and

Hellraiser

gave him the chance to simultaneously play with such devices and stay true to his own creed of gorgeous grotesquery. But like that other gore fest of the year before—David Cronenberg’s remake of

The Fly

(1986)—the special effects do not overshadow the story. Indeed, Barker learned a very important lesson from Cronenberg and his penchant for staging shocking scenes quite early on in his films (the exploding head in

Scanners

(1981) for example). The introductory sequence in

Hellraiser

is radical, but it does grab the viewer and buy Barker exposition time. One of the reasons

Hellraiser

has stood the test of time is the fact that there is a solid, appealing and emotional story at its center. The effects only supplement this. To have it the other way around would be, as Barker says, “The tail wagging the dog.”

6

Hellraiser

can be situated within the whole Body Horror subgenre, in which Cronenberg’s films definitely belong, but again these are not mutations or disfigurements for the sake of them. As in the

Books of Blood

, the transformations of the flesh have a purpose beyond mere superficial spectacle: Frank’s escape and taking on his brother’s form, the Cenobites’ intermingling of pain and pleasure. In a movie like

The Fly

, the slow deterioration of the body, the shock at what might be revealed next, starts to become the only impetus. Frank is the antithesis of Brundle, an attempt to make the ugly human and natural, instead of rendering the beautiful repulsive.

Similarly, jump-shocks do not age well in cinema. Films designed to be like Ghost Train rides, where one fright follows the next, date incredibly quickly.

Hellraiser

has two such shocks: when one of Frank’s victims pleads with Kirsty for help; and the double whammy of Christ and the maggoty corpse dropping out while Kirsty is trying to hide from Frank. These scenes, added at the behest of New World, who thought that a horror movie should have some sudden scares in it, are the least satisfying in the whole film. They are obvious and seem unnecessary on repeated viewings.

But if

Hellraiser

by and large seemingly refuses to pander to these rules of horror cinema, it is still visually informed by other historical horror models. Indeed, it simultaneously pays homage to and transcends them. First, Barker acknowledges the mythology of the vampire subgenre—in his use of blood as a regenerative source. Frank may not have fangs and bite people on the neck, but he is still a vampire. As well as binding the family unit together, blood brings Frank back from the dead and he feeds off the victims Julia (his vampiric bride) lures to the house (their castle). So in this sense too, the blood and gore have value beyond the obvious.

Alternatively, the resurrected Frank could also be described as a zombie, one of the walking dead, feasting on human flesh. True, he can think coherently, which is more than Romero’s shambling corpses can do, but he is, to all intents and purposes, dead: we saw him ripped apart at the beginning. In a slightly different tone, there are some shots which are pure Gothic in nature, such as one high angle glimpse of Julia at the top of the stairs, her face half in shadow. And Barker pays homage to the haunted house and ghost film, in the most obvious way, with the location house itself, which looks suspiciously like a well-known property in Amityville, and with the ghost presence of Frank in the attic—the oldest form of shade.

Lastly, Barker includes a creature that would not look out of place in any monster or alien film. As we have commented, the Engineer does appear remarkably cheap compared with what might have been accomplished with more time and money. But thanks to Vidgeon’s lighting again and Richard Marden’s editing, it is nowhere near as deficient as Rawhead Rex. On the contrary, there is an inherent substance and charm to it that could never be replaced by computer generated trickery.

Grand Guignol poster (courtesy of Eric Horton).

Both the British Board of Film Classification and the Motion Picture Association of America insisted on cuts to

Hellraiser

, to the tune of twenty seconds. But there was trimming only within scenes where both bodies thought the intensity was too much, and no scenes were lost in their entirety. For a final word on his motivations for creating such images, we’ll turn to Barker once more: “I think it’s a desire that the audience comprehend that these images are highly charged and mythic, and worthy of our close examination. And if we just go out and say, ‘That was gross,’ then we’ve missed most of the purpose of that image. It’s difficult. You have to create very elegant images and very elegant metaphors. I hope there are places in

Hellraiser

where I have done that. It’s a picture which should work on more than one level.”

7

5

NO LIMITS

Critical reaction to Clive Barker’s

Hellraiser

upon release was generally favorable on both sides of the Atlantic. London magazine

Time Out

had this to say: “Barker’s dazzling debut creates such an atmosphere of dread that the astonishing set-pieces simply detonate in a chain reaction of cumulative intensity ... a serious, intelligent and disturbing horror film,

Hellraiser

will leave you, to coin one of Barker’s own phrases, in a state between hysteria and ecstasy.’”

While

Melody Maker

proclaimed it was, “The best horror film ever to be made in Britain,” which is saying very little at that time,

City Limits

encapsulated the attraction quite neatly with these words: “Barker exploits our deepest dreads about pain equals pleasure and the fears that our socially repressed primal desires will one day unloose and end in a sexual nightmare.”

The Daily Telegraph

commented that, in

Hellraiser

, “Barker has achieved a fine degree of menace.”

The Daily Mail

called the film, “A pinnacle of the genre.” And

The Scotsman

said, “It plays on the darkest fears and fantastical obsessions of the human psyche.” The more academic magazines also took an interest, and horror writer and film historian Kim Newman hit the mark with his critique in

Monthly Film Bulletin

: “The most immediately striking aspect of the movie is its seriousness of tone in an era when horror films (the

Nightmare on Elm Street

or

Evil Dead

films in particular) tend to be broadly comic. ... the overall approach is straight, not to say relentlessly grim.”

1

And while

Q Magazine

echoed these sentiments, they also drew attention to the U.S. dubbing imposed by New World: “

Hellraiser

does have its share of problems: the re-dubbing of peripheral characters with a mid–Atlantic twang, the relocation of the film in a geographical limbo.... The film, however, cannot be faulted for the ambitiousness of its themes.... Sadly the moral and emotional complexity that is the film’s greatest strength is likely to be deemed its greatest weakness by an audience weaned on the misplaced jocularity of

House

or

Fright Night

.”

Screen International

also decided to concentrate on the scare tactics for their review, calling the film “The best slam-bang, no-holds-barred, scare-the-shit-out-of-you horror movie for quite a while.”

Oddly, the most savage criticism came from the U.S., although industry magazine

Variety

did say in their Cannes review that

Hellraiser

was “a well-paced sci-fi cum horror fantasy which should appeal to a wide youth audience around the globe,” and the

New York Times

called it “evocatively creepy.” The first barrage came from famous film critic Roger Ebert of the

Chicago Sun Times

: “Stephen King ... may have seen the future of the horror genre, but he has almost certainly not seen

Hellraiser

, which is as dreary a piece of goods as has masqueraded as horror in many a long, cold night.”

Richard Harrington was no less unpleasant in his

Washington Post

review of September 19, 1987: “Some things have to be endured.... That’s what one of the characters says in Clive Barker’s

Hellraiser

, and he might as well be talking about the first film written and directed by this new enfant terrible of the horror genre....” Thankfully, there were some who didn’t share these views, Michael Wilmington from the

Los Angeles Times

for one. He said: “Clive Barker’s

Hellraiser

is one of the more original and memorable horror movies of the year: a genuinely scary, but also nearly stomach-churning experience by a genre specialist who seemingly wallows in excess and loves pushing conventions to their ghastly limits....

Hellraiser

is intelligent and brutally imaginative.”