The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy (26 page)

That job went to Randy Miller, whose first score had been for the 1988 movie

Witchcraft

(Rob Spera). Miller was given just over three weeks to compose an hour’s worth of music, which—due to budgetary constrictions—would be performed by Russia’s Mosfilm State Choir and Orchestra. Miller became the first American to score a Hollywood film in the newly privatized Russia, spending ten days there recording the material. However, he himself had concerns about their ability to play the score he’d written and their recording techniques: “You can throw the most difficult music in front of an American studio orchestra, and they’ll be able to play it in a minute,” he said, “but Mosfilm wasn’t used to that quick pace, and it took a lot of rehearsals to get the score right. I insisted on a certain level of excellence, and while the Russians may have gotten a bit annoyed with me during rehearsals, they were glad that I pushed them.”

29

Much of this annoyance is translated into the music, making it the angriest

Hellraiser

score yet. The subtler, more suspenseful moments with violins—for example in the track “Back to Hell”—are suddenly interrupted by violent booms and a repetition of the composer’s main

Hell on Earth

theme. A more pacy, action oriented melody, this is at times disjointed and has none of Young’s majesty. Thankfully, Young’s themes do appear sporadically, as in “Cenobites Death Danse,” used in its entirety for the opening credits sequence, but here they only serve to remind us that the days of the first two movies are long gone. Miller did, though, come up with a memorable new theme for “The Pillar,” which he uses again in “Elliott’s Story.” None of this is to say that Miller’s score is bad; it simply reflects how different

Hellraiser III

is to its forebears.

Shooting began in late 1991, with Bradley and Atkins being flown over to the U.S. and meeting Hickox for the first time. Said Bradley, “I didn’t meet Tony until I got to North Carolina, which was my first experience of working in the States. And I just got on with him straight away. Maybe the English sense of humor thing worked as well? It was a curious kind of crossover point. It was the point at which the A-Team, so to speak, who had been responsible for

Hellraiser

and

Hellbound

, were starting to move out of the equation. But Pete was still there, Bob Keen and the Image Animation Team was still there, and I was still there.”

30

Atkins, who was needed on hand in case there were anymore changes to be made to the script, summed it all up more succinctly: “I guess we’re not in Cricklewood anymore, Toto,” he commented to Bradley as they were driving to film a location scene, “and it sure ain’t Pinewood.”

31

The movie itself was shot in Greensboro and High Point, a tiny town which is the furniture capital of America. It would double as the New York setting, and a furniture factory would be transformed into the Boiler Room. In complete contrast to the conditions on the first movie, the studios were right at the back of the hotel, with one huge soundstage and four sets which were within walking distance of each other—good in one sense, but quite difficult if the second unit films a scene at the same time as the first in close proximity, especially when working at such a fast pace.

Undoubtedly this was one of the major criticisms of the shoot. Zach Galligan had remarked during the filming of

Waxwork II

about the speed Hickox worked at: “The first two or three days were difficult, getting used to the pace at which Tony operates. He does 50 or 60 set-ups a day, which is almost unheard of. It’s three times more than I usually do, and there are no stand-ins, so we’re constantly on the set, constantly working.”

32

The fact that there was only an eight week break between that movie and

Hell on Earth

seemed to do nothing to slow the director down. It was something that Bradley saw as a downside as well. “Clearly Tony enjoys working fast and doesn’t mind the long hours. Yesterday, I clocked up my longest day ever, seventeen hours in total. It has to be fast to achieve everything in the six weeks Trans Atlantic Entertainment allotted the production. But you can’t linger to get things right and that’s frustrating.”

33

Hickox also preferred to edit in camera, which again speeded things up but occasionally made it very difficult for the actors. In effect they were working in close-up with just the storyboards to give them some idea of how the finished thing would look.

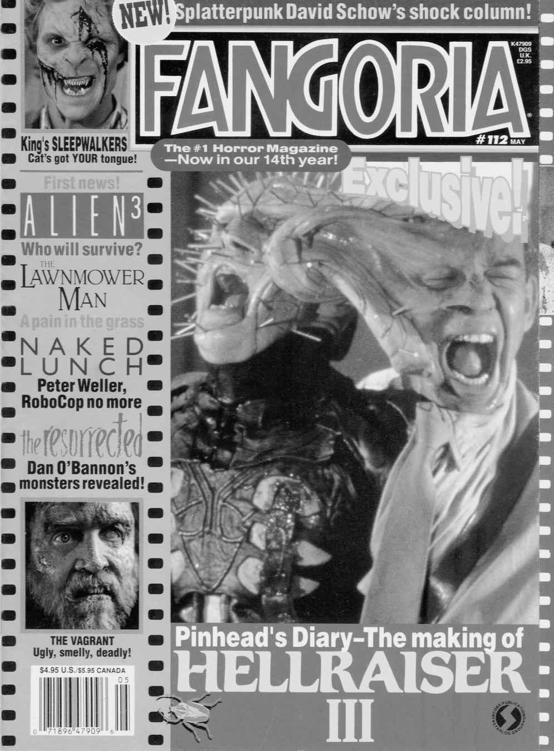

A

Fangoria

cover showing that schizophrenic moment when Elliott and Pinhead merge (courtesy Starlog Group).

Bradley also experienced a number of other problems on the set. The first was his scenes inside the giant Pillar of Souls. The actor had to hold on to two bars inside and put his head through the gap; not the most comfortable of positions. And deprived of any movement other than facial, Bradley had to make his words count even more. It is a testament to his dedication, and to Atkins’ writing that these Pillar scenes work so well. The next concern was make-up related. With Paul Jones taking over from Geoff Portass, when it came to applying the make-up there were noticeable changes. The application was much faster, with the look totally redesigned. There were fewer pieces of latex and the nails were now plastic instead of metal, which helped them sit better on Bradley’s face. But they had a tendency to bunch up, making it not quite as clean as the first two make-up jobs. This might be the reason Bradley has said it is his least favorite make-up of all the films.

34

Pinhead’s flesh color is also different, more beige than blue-white, not helped by some of the lighting effects and a completely misjudged dream sequence where he is filmed outside in a field. Meant to be seen on a set or at night, the make-up simply doesn’t look right in daylight. One good thing, though, was that Bradley was able to find an optician in Greensboro who could make him prescription black lenses. Whereas before he had only been able to wear the contacts for twenty minutes at a time, now he could comfortably shoot scene after scene.

A final concern revolved around the shooting of the climax when Elliott and Pinhead are seen at the same time. As he related in his diary for

Fangoria

:

Saturday, October 19—It’s a positively schizophrenic night for me as we shoot the climactic confrontation between Pinhead and Elliott, starting out in human form and switching to Cenobite at about 2 a.m.... I’m completely tripped out by the sight of Pinhead standing there, waiting for me. Kevin, my stand-in, has won the nomination to double Pinhead. I point out that he’s the only other person ever to have worn the full Pinhead make-up and costume.... I suddenly realize just how jealously protective of the character I’ve become. It is deeply unsettling for me.

35

But in spite of these niggles, Bradley was more than happy during his time in the U.S. His part had more depth, he got to perform as both a human and a monster, and he had nothing but praise for both the production team and the film’s director. In several different interviews he’s claimed that

Hell on Earth

was one of the happiest working experiences he’s had.

The smoothness of the shoot and professionalism of the crew were also noted by both Alan Jones on a set visit for

Shivers

and

The Dark Side

, and Philip Nutman for

Fangoria

. Nutman’s visit coincided with the filming of the scene fourteen days into principal photography where the Pseudo Cenobites are harassing Joey on an abandoned work site. “The director talks his young thespians through the next shot. It’s taken from Joey’s point of view, as J.P. and the female Cenobite (Marshall) circle her, while Barbie, Camerahead and C.D. advance from the background.”

36

After four takes, everyone was satisfied and they set up the scene again to film it from Pinhead’s point of view. The only major reproach was about the skimpiness of Marshall’s costume—fishnet stockings and a leather bodice in the freezing cold of a winter’s evening.

By the same token, Jones’s interviews with Atkins, Bradley and Hickox reveal a general air of conviviality about the shoot, with the possible exception of some unrest when it came time to film the black mass scene. Hickox had already been refused permission to film in an actual church—hardly surprising, given the content of the scene: Pinhead’s very own reworking of a Christian sacrament—so a matte background would have to be painted around the Church’s aisle and altar. But, due to Carolina being in the heart of Bible Belt country, many members of the crew were startled by the display itself, murmuring “sacrilegious” under their breath, according to Jones. Hickox’s reply to that was, “Is it really so controversial? I don’t see it as that, well, no more than Christopher Lee storming around a church setting light to curtains in umpteen

Dracula

movies. The crux of the sequence is that Pinhead fights back against the power that abandoned him. So the Church fights back, too, by crumbling around him and turning into Hell, the one place he doesn’t want to be.”

37

Aside from a little healthy rivalry in the acting stakes between Marshall and Farrell, which Hickox actually welcomed because it meant they upped the ante in their scenes together, there weren’t that many more obstacles during the filming itself. These, it would seem, were being reserved for post-production. The first problem came in the shape of the infamous EDIFLEX editing technology that Larry Kuppin suggested Hickox use, because he owned the company. But the process itself proved incredibly onerous, involving banks of videos in the editing bay. It was so time-consuming that in the end they had to revert to film. By this stage, the independent distribution company Miramax had picked up

Hell on Earth

for an American release and a rough cut was shown to them.

This is where the story splits into two versions, depending on who is telling it. Hickox maintains that Miramax’s co-owner, Bob Weinstein, who wanted to pick up a horror franchise and start Dimension films, saw a rough cut and loved it. But he asked the director, if he had a week more to shoot and some more money for effects, what would he do? Hickox told him that he’d like to add some more substance to the nightclub scene where Pinhead attacks the revelers, and redo the ending. So he was given the time and budget to do just that. This is how

Hellraiser III

became a groundbreaking film in terms of special effects technology.

Computer Generated Images, or CGI, was still only in its infancy in Hollywood. A few artists had dabbled with this new toy, one of the earliest examples being the Knight from

Young Sherlock Holmes

(Barry Levinson, 1985). But it wasn’t really until James Cameron’s spectacular

Terminator 2: Judgment Day

(1991), with its impressive liquid metal T-1000, that people in industry circles started to take notice.

Hell on Earth

was the first horror movie to utilize CGI, expressly for the scene where a glass of liquid solidifies and spears one woman in the face, Sandy’s skinning—and morphing effects when Joey’s father turns into Pinhead, as well as when Elliott and Pinhead merge. Remember, this was still a year before Steven Spielberg popularized CGI with his blockbuster

Jurassic Park

.

Conversely, Clive Barker has a different recollection of events. In his version, Larry Kuppin showed him a rough cut of the movie, which Barker was less than impressed with. “I told him that although it contained some great moments, there was a lot of stuff missing; the ending wasn’t right, there was no climax, I didn’t understand some sequences, and in parts the story was incomprehensible. But, true to his [Hickox’s] skills, it was beautifully composed and photographed, the actors were nicely framed and the images did look slick.”

38

According to Barker, the low budget was also to blame when it came to the less than impressive effects.

39

Barker says he turned down an offer to put his name to it, wished Kuppin good luck, then returned to his own duties serving as executive producer on

Candyman

, an adaptation of Barker’s own story “The Forbidden.” This would be around the time that the Miramax deal was struck.