The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy (41 page)

Thorne has no idea that he is playing yet another game, one he cannot possibly win. And his opponent this time is Pinhead. The chess game should have been a clue, as it is a distant cousin to Lemarchand’s dolls. This is investigated more fully in Pinhead’s speech at the climax: “It’s all a puzzle, isn’t it Joseph? Like a game of chess. The pieces move, apparently aimlessly, but always towards a single objective: to kill the king.” Thorne’s reality is Pinhead’s own giant chessboard and the people on it no more than expendable pawns.

The allusions to the sport of fishing serve to illustrate this, too, when they enter Jay Cho’s crime scene—“Ever go fishing, Tony?”—and when Thorne informs his wife, “Actually I

caught

a case.” Thorne is used to being the one with the rod, but suddenly things have turned around. The hooks and chains are directed at him during the finale. And now that the viewer realizes Tony is merely a construct of Hell, it is safe for him to admit to Thorne that he’s been fishing as well.

Once again, this desire to win probably stems from Thorne’s lonely upbringing. We see him in flashback playing alone in his room; the adult Thorne looking out of the window to show us we are on a farm miles from anywhere. Thorne had only his parents for company, and subsequently abandoned them in later life. “Why don’t you visit us, Joe?” asks his mother sitting by his father’s bedside. This isolation accounts for the reason why he uses his magic tricks to entertain himself rather than his daughter. The sleight of hand as he palms the coke at the first crime scene, then brings it out again when he’s with Daphne, is just for his own amusement, as are the worry balls he plays with constantly during the film. “That’s a Chinese thing, isn’t it?” says Gregory with tongue firmly in cheek, an obvious reference to the puzzle box. Thorne has spent so long challenging himself he thinks nothing of trampling over his rivals.

But in

Inferno

the competition is the greatest game player of them all.

Pins and Needles

Still, the most interesting aspect of

Inferno

is the fact that

Hellraiser

’s influence—like Thorne’s word puzzle—has come full circle. When the original came out, body piercing was more of an underground scene, and certainly not as prevalent as it is today. The series must take some credit for popularizing the art of adorning one’s flesh with metal. In the documentary

Hellraiser Resurrection

, Barker enforces this: “Now there’s a whole movement of people who’ve made an art form of their bodies, piercing, scarification, brandings of various kinds. Back then [when

Hellraiser

was made] it was much, much harder to see that; there was much less of that around.”

2

The performance artists Puncture, who also feature, confirm: “

Hellraiser

is like a breeding ground for our imaginations, for our next performance.”

3

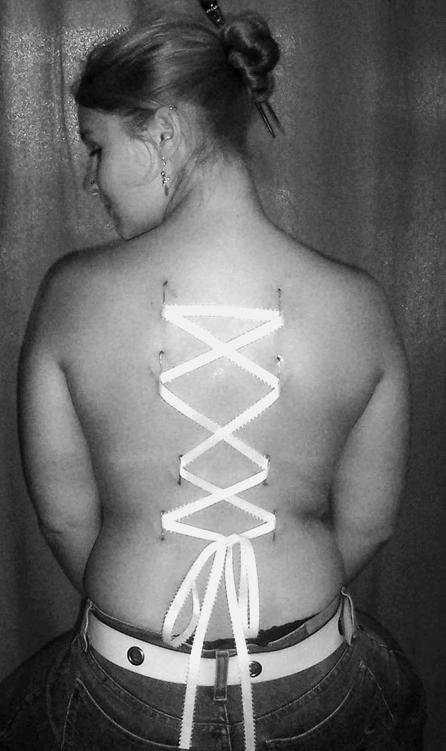

Life imitating art imitating life. An example of body piercing, the back corset. Piercer: Shorty, West Palm Beach, FL. Model: Kacey (www.theshorty.com. Photograph courtesy Marc Calma).

In

Hellraiser V

we are taken to Leon’s Stigmata body piercing parlor, introduced by shots of the pictures on his wall. Black and white images of needles through the eyebrow and nose, stitched lips, latticed backs, hooked nostrils, give way to a live procedure of someone having their tongue pierced with a large spike. Into this world comes Thorne, to ask Leon about the Lament Configuration. Leon himself is bald, covered in tattoos, and has a hook through his nose. On his walls hang studded collars and a lethal multistranded whip with hooks on each of its ends—the same one used in Bernie’s death later. This is the influence of

Hellraiser

in the real world, but it is an effect Thorne cannot possibly understand. The only metal he has on him is his badge and his gun, which is why it takes him so long to figure out the enigma and why the Cenobites appear so alien to him. Here

Inferno

is art imitating life, which in turn has been already been influenced by art.

21

WELCOME TO HELL

It was anticipated to a certain extent, but no one could have predicted the sheer disappointment of

Hellraiser

fans who bemoaned the virtual absence of their favorite Cenobite in the new film. “The series had become the Pinhead show,” stated Derrickson in retrospect. “Personally, I’m very happy about the lack of Pinhead in

Inferno

, but if I had to do it over again, I’d put a bit more of him in there for the sake of the fans.”

1

To have held back with Pinhead was one thing, but it was the use of his image for promotional purposes that seemed to upset people, as Bradley suggested: “What irritates me, and I know it upsets the fans as well, was that they then smothered the video cover with pictures of Pinhead, and that tells everybody it’s his film again—he’s the featured character. Well, no, he isn’t, so don’t sell it on that.”

2

Barker, too, was displeased by the film, as evidenced in a question and answer session at a

Hellraiser

screening in Los Angeles in August 2000: “I really don’t like to say this about another’s work but I really hate this movie and it seems to have violated a lot of the things that I like about

Hellraiser

.”

3

They were thoughts he reiterated in the

Lost Souls

newsletter: “[

Hellraiser: Inferno

] is terrible. It pains me to say things like that because nobody sets out in the morning to make a bad movie....”

4

Derrickson’s chess move was to send an e-mail to

Esplatter

arguing his case, “[Clive’s] reaction, I must admit, was not entirely unexpected.... I never expected that he would appreciate seeing the treasured iconography of his brainchild tossed out of the window and replaced by a whole new set of rules. But it seems to me that I made a movie that is too good, or at least too provocative, for him to just simply dismiss.... This is, in fact, a very good film. It is philosophically ambitious (unlike

Hellraiser

II, III, or IV), and it represents a moral framework outside that of the previous

Hellraiser

films and (apparently) outside that of Clive Barker’s personal taste. Quite simply, I subverted Clive Barker’s franchise with a point of view that he does not share, and I think that really pisses him off.”

5

The reviews, on the whole, came down on the side of Barker and Bradley.

Fangoria

’s Allan Dart compared the film to that of

Halloween III

and

Friday The 13th Part V

, which also abandoned their original concepts in favor of a new start but were lambasted by the fans: “And while

Hellraiser: Inferno

doesn’t completely disregard its Pinhead origins, it is guilty of demoting everybody’s favorite Cenobite to a bench player on a losing team....” He goes on to compare the lead character of Thorne to the director, saying, “The person who is really in over his head is co-scripter/director Scott Derrickson. His demon-haunted detective tale, while not bad on its own, doesn’t belong in the

Hellraiser

storyline. It’s an odd and uncomfortable fit that makes Derrickson, like Joseph, damned from the beginning.”

David Trier at Movie Vault reported that

Hellraiser

was a series close to his heart and so approached this new installment with the lowest of expectations. But he was impressed that this was a self-contained movie with coherent beginning, middle and end (unlike, in his opinion,

Bloodline

) and liked the sense of style it displayed. His reservations, though, revolve around those same questions again: “There are two main things that keep this from being a ‘good’ movie. First and foremost, it is not a

Hellraiser

movie. The presence of the box and the minute or two of Pinhead’s screen time are the only things that tie it to the series.... Pinhead’s provoking commentary has always been one of the greatest assets to the series and I could tell Doug Bradley just wanted to cry. It’s really just a supernatural detective story....”

Efilmcritic.com reviewer Scott Weinberg, like Bradley, was concerned for the fans: “Here’s what I don’t get: A studio goes to all the trouble of producing a new horror sequel, but time and again they simply refuse to acknowledge that these movies have fans and followers, people who love the series and will pretty much rent any movie with a number in the title.”

The consensus of opinion tended to be that as a stand alone film this might have worked better, but as a

Hellraiser

movie there weren’t enough elements from the mythos to warrant the title. Incredible as it may seem, Derrickson was asked if he wanted to direct the next film in the sequence as well, but he declined as he and Boardman were already working on other projects, one a thriller for Dimension. So it would be time for yet another person to take charge of the franchise. Would that person stay faithful to the mythos or carry it on in the direction

Inferno

had taken it? Only time would tell.

22

HIDE AND SEEK

The person chosen by Dimension to immediately follow up

Inferno

was cinematographer Rick Bota, who had begun his career—like Kevin Yagher before him—working on episodes of

Tales from the Crypt

. Not the best omen

Hellraiser

supporters could have wished for. But he also had ten years of experience on films such as

Final Embrace

(Oley Sassone, 1992), Pamela Anderson’s flashy—in more ways than one—comic book flick

Barb Wire

(David Hogan, 1996), the interesting though inferior remake of

House on Haunted Hill

(William Malone, 1999) and serial killer jaunt

Valentine

(Jamie Blanks, 2001) starring

Angel

heartthrob David Boreanaz. In addition to this, Bota had been a second unit director on Guillermo del Toro’s impressive monster movie

Mimic

(1997) starring Mira Sorvino, and

Kiss the Girls

(Gary Fleder, 1997), with Morgan Freeman taking up the role of Dr. Alex Cross from James Patterson’s successful novels.

Providing the script this time would be two writers. Carl V. Dupré had been a writer on TV’s

Bone Chillers

(1996), had penned

Detroit Rock City

(Adam Rifkin, 1999),

Prophecy 3: The Ascent

(Patrick Lussier, 2000) and

Broke Even

(David Feldman, 2000), but had cut his teeth in the industry working in a variety of positions since 1992, from assistant editor to production assistant. This was also true of Tim Day, who had started out as electrician on

9½ Ninjas!

(Aaron Barsky, 1991) and Anthony Hickox’s

Waxwork II

(1992), before working as best boy and key grip on a number of productions. Day was actually an old friend of Bota’s from his

Tales from the Crypt

days. The now titled

Hellraiser: Hellseeker

would be his first writing assignment, but between the pair of them they had a wealth of filmic experience which they could draw on when fleshing out the story. They were also, quite obviously, fans of the

Hellraiser

canon, which is why the script is peppered with homages to previous films in the series (even down to calling places of work Cubic Route and Kircher Imports after the character who provides Frank with the box in

The Hellbound Heart

novella).

But it is fair to say that without

Inferno

’s influence

Hellseeker

probably wouldn’t have been the screenplay it was, hinging, as it does, around the gradual descent into madness of a man who loses his wife in a car accident, then has to piece together the mystery of what’s happened. A further resemblance arises when we discover that someone has been killing the other people in his life, such as his boss, his neighbor and his best friend at work. Time is also nonlinear, as it was in

Inferno

, and the lead character of Trevor experiences flashbacks and jumps in time, which may or may not have been caused by a head injury after the accident. And he gets his just desserts at the end, exactly like Thorne, when he discovers he is dead, too. What was particularly exciting about the script, though, was the missing wife’s name: Kirsty.

Dupré and Day had originally intended to bring back the character of Kirsty from the first three

Hellraiser

films, a fascinating and attractive idea for long-term devotees of the mythos, but Bota and the team had trouble contacting Ashley Laurence. The character then had to be altered to make her a new one, the name remaining in deference to both the character and the early films (and the couple’s friendly pit bull took on the name of Cotton). This was the version of the script sent to Doug Bradley, who was initially intrigued to read that Kirsty was in it, then disappointed to discover that it wasn’t Kirsty Cotton. Because negotiations for the role of Pinhead were left until quite late into preproduction, Bradley didn’t get the chance to discuss this with Bota. He got on with the director immediately, impressed by his enthusiasm and distinct vision: Bota had been very influenced by avant-garde art and was extremely interested in colors because of his director of photography background.