The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy (6 page)

Undoubtedly, the fact that cast and crew were all living in close proximity to each other, some in the location house itself, gave the shoot a communal feel that harked back to the days of the Dog Company. Perhaps this accounts for why Barker relaxed into his stride so quickly. He knew how to deal with actors, he knew how to tell stories visually; all that was lacking was the technical expertise, which he picked up as the production progressed.

Original Frank make-up reference head (courtesy Phil and Sarah Stokes of the Revelations Web site www.clivebarker.info).

Most crucially there was this underlying ethos to spur him on: “The force of imagination behind these things is finally more important, I believe, than knowing the rules, because somebody else will help you with the rules. That’s what technicians are there for, to say no, no, you can’t possibly do that, it’ll be out of focus. And that’s fine—you learn as you go along.”

39

Obviously, no production is all plain sailing, particularly a first time one. Bradley had trouble hitting his marks the first time in make-up because he couldn’t see through his black contact lenses, and he was also frightened of tripping over Pinhead’s skirts. He had a difficult moment on a wooden support that was being raised into the air above Kirsty, and tumbled off. There were reports of some tension between Robinson and Barker over how to play certain scenes, possibly not helped by the new director finding his feet,

40

so much so that Barker described his job as being 50 percent diplomat. They had to rush a shoot in a Chinese restaurant between Kirsty and Larry because the man who was supposed to let them in was late, the consequence of which is one of the flattest scenes in the whole film. The Engineer creature, that Barker actually spent evenings with the special effects team helping to construct, proved cumbersome to maneuver—in fact, if you watch the scene closely where it runs down the hallway, you can see the men operating it and pushing it from behind. Additionally, there was little time and money to effectively destroy the house for the denouement. Handfuls of dust and a few bits of wood falling from the roof have to stand in for this. But, taking everything into consideration, it was a much easier shoot than some (

The Exorcist

comes to mind). There was also nothing like the misfortune that would plague Barker on his next movie as director (see Chapter 11).

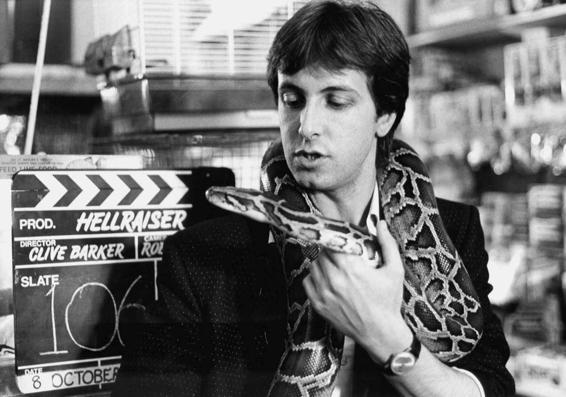

Clive Barker on set (photograph credit Tom Collins).

When filming wrapped, the editors proved no less considerate: Richard Marden, who had worked with John Schlesinger and David Lean, and an uncredited Tony Randel. Marden, who started out in the business as sound editor on

The Vicious Circle

in 1957 (Gerald Thomas) and was responsible for editing such diverse films as

Bedazzled

(Stanley Donen, 1967) and

Half Moon Street

(Bob Swaim, 1986), was apparently the “soul of tact” when Barker sat in on the process.

Finally, the importance of Christopher Young’s music cannot be underestimated. Barker originally wanted the electronic band “Coil” because he claimed their music made his “bowels churn,” although unit publicist Stephen Jones tactfully suggested that cinema management might prefer it if he said “spine chill” instead.

41

However, the idea was rejected by New World and it was actually Randel who brought New Jersey native Young into the

Hellraiser

stable. No stranger to working in the science fiction and horror fields, Young had provided the music for movies like

Godzilla

(Koji Hashimoto and R.J. Kizer, 1985) and

A Nightmare on Elm Street Part 2: Freddy’s Revenge

(Jack Sholder, 1985). Strangely, his compositions would mark

Hellraiser

out as distinct from such fare, in particular the slasher flicks of the

Nightmare

series, which was into its third installment by 1987. From the very opening bars of the movie the majestic signature tune speaks of deadly elegance, a much more classy horror film. And who can imagine Frank’s resurrection sequence without the celebratory waltz?

Hellraiser

soundtrack by Christopher Young (cover courtesy Silva Screen).

Barker has said in retrospect about the musician, “In a sense he made a larger mark on the movie than practically anyone else associated with it, because his score elevates the picture with its scale, majesty, complexity and emotional richness. Chris is an old style composer, and a little crazy I think—and he’d probably admit to that. An extraordinary talent.”

42

High praise, but then Young did give the director a crash course on spotting and scoring, continuing his involvement in the project at every level. Barker even pitched in with the people at New World’s publicity, marketing and distribution departments—unaware as he was at that time of the significance of a really excellent marketing campaign (it can make or break the picture, as he discovered later in his career). From the beginning, Barker was the driving force behind this project. And he was there right at the end when, upon its general release,

Hellraiser

recouped its production costs in just three days.

2

OPENING THE BOX

Deals with the Devil

Faustus, ah Faustus! Poetry, perversity, farce and damnation! What more could I ask for? I adored its rapid changes of tone, its sheer theatricality.

—Clive Barker, “Keeping Company with Cannibal Witches,”

Daily Telegraph

, January 6, 1990.

As befits a story based around the Faustian myth, the overriding theme of

Hellraiser

is the bargain, or pact. The tale originates from fifteenth and sixteenth century Germany where a Dr. Georgius Faust of Helmstadt encouraged the rumor that he had sold his soul to the devil in exchange for magical powers. This was transcribed as

Historia von Johann Fausten

(1587), and translated into English as

The Historie of the Damnable Life, and Deserved Death of Doctor John Faustus

. Around the same time, Christopher Marlowe reworked the story as

The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus

, in which a scholar trades his soul to the demon Mephistopheles for knowledge and is sucked into the pits of Hell. In Barker’s own words, “It tells of a shaman who touches an inner darkness—a forbidden place that promises dangerous knowledge—and is snatched off by the very forces he’s hoped to control.”

1

But in Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s nineteenth century verse drama,

Faust

, the main protagonist escapes his damnation by cheating the demon Mephisto.

Hellraiser

’s story of Frank Cotton and the Cenobites, therefore, is a skilful conjunction of the last two. Although, this being Barker, there is no escape for long.

The very first scene depicts a deal in the process of being struck. Frank is asked, “What’s your pleasure?” by the merchant. The pleasure Frank seeks is not magical powers or knowledge, but the ultimate in sexual and hedonistic experiences. Frank is the quintessential thrill-seeker who has been constantly searching his whole life for something “more.” The small ivory ornament of a man and woman coupling and the photographs he leaves behind all point to his particular weakness for pleasures of the flesh. Unfortunately, “It’s never enough.” And his brother’s line about Frank never being one to kick cash out of bed denotes that he has always been willing to pay for his enjoyment. Later, Frank confesses to Julia, “I thought I’d gone to the limits. I hadn’t. The Cenobites gave me an experience beyond limits. Pain and pleasure, indivisible.” Frank strikes a deal for the box, hands over his cash, expecting his version of pure pleasure. It isn’t until later that he discovers not everyone’s idea of “pleasures of the flesh” are the same.

Desire and gratification are at the heart of the next deal we see, too; indeed, they intertwine with this theme throughout the film. In the attic flashback scene where Julia remembers her own sexual brush with Frank, two critical bargains are made. Just before they make love, Julia asks Frank, “What about Larry?” to which he replies, “Forget him.” This is the price

she

must pay for his favors. Incidentally, it must be pointed out here that the sex scene in the finished movie isn’t the original one Barker scripted and filmed. In this version, the act is longer and much more passionate, as this screenplay extract shows:

Their love-making is not straight-forward: there is an element of erotic perversity in the way FRANK licks at her face, almost like an animal, his hold too tight to be loving. The sequence escalates into a series of strange details from their locked bodies. Nails digging into palms; sweat rivulets running down their torsos. And once in a while we see their faces. JULIA watching FRANK, mesmerized and amused by his intensity.

2

Barker wanted there to be no doubt in the viewers’ minds that she’d never experienced anything like this before; so intense it has stayed with her all these years. Interestingly, though, it was New World who forced the director to cut back on the sex and introduce the switchblade element—where Frank cuts the strap of Julia’s chemise. “I lost the situation I’d written,” explained Barker in a later interview, “which was they fuck like crazy. I wanted to motivate her with this incredibly raunchy sex scene, they said, ‘sorry, we simply can’t use this material because you can’t mix sex with violence’.... I could only hint at that.”

3

The idea was that Julia feels excited and alive rather than in danger—this is no rape—and that’s an important distinction when it comes to the second bargain the lovers make.

Julia and Frank. Hellraiser still (photograph credit: Tom Collins).