The Hiding Place (9 page)

And so I learned that love is larger than the walls that shut it in.

M

ORE AND MORE

often, Nollie's conversation at the dinner table had been about a young fellow teacher at the school where she taught, Flip van Woerden. By the time Mr. van Woerden paid the formal call on Father, Father had rehearsed and polished his little speech of blessing a dozen times.

The night before the wedding, as Betsie and I lifted her into bed, Mama suddenly burst into tears. With Twenty Questions we discovered that no, she was not unhappy about the marriage; yes, she liked Flip very much. It was that the solemn mother-daughter talk promised over the years for this night, the entire sex education which our taciturn society provided, was now not possible.

In the end, that night, it was Tante Anna who mounted the stairs to Nollie's room, eyes wide and cheeks aflame. Years before, Nollie had moved from our room at the top of the stairs down to Tante Bep's little nook, and there she and Tante Anna were closeted for the prescribed half-hour. There could have been no one in all Holland less informed about marriage than Tante Anna, but this was ritual: the older woman counseling the younger one down through the centuriesâone could no more have gotten married without it than one could have dispensed with the ring.

Nollie was radiant, the following day, in her long white dress. But it was Mama I could not take my eyes off. Dressed in black as always, she was nevertheless suddenly young and girlish, eyes sparkling with joy at this greatest occasion the ten Booms had ever held. Betsie and I took her into the church early, and I was sure that most of the van Woerden family and friends never dreamed that the gracious and smiling lady in the first pew could neither walk alone nor speak.

It was not until Nollie and Flip came down the aisle together that I thought for the very first time of my own dreams of such a moment with Karel. I glanced at Betsie, sitting so tall and lovely on the other side of Mama. Betsie had always known that, because of her health, she could not have children, and for that reason had decided long ago never to marry. Now I was twenty-seven, Betsie in her mid-âthirties, and I knew that this was the way it was going to be: Betsie and I the unmarried daughters living at home in the Beje.

It was a happy thought, not a sad one. And that was the moment when I knew for sure that God had accepted the faltering gift of my emotions made four years ago. For with the thought of Karelâall shining round with love as thoughts of him had been since I was fourteenâcame not the slightest trace of hurt. “Bless Karel, Lord Jesus,” I murmured under my breath. “And bless her. Keep them close to one another and to You.” And that was a prayer, I knew for sure, that could not have sprung unaided from Corrie ten Boom.

But the great miracle of the day came later. To close the service we had chosen Mama's favorite hymn, “Fairest Lord Jesus.” And now as I stood singing it I heard, behind me in the pew, Mama's voice singing too. Word after word, verse after verse, she joined in, Mama who could not speak four words, singing the beautiful lines without a stammer. Her voice which had been so high and clear was hoarse and cracked, but to me it was the voice of an angel.

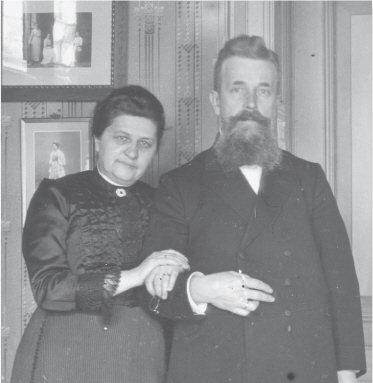

Cornelia and Casper ten Boom.

All the way through she sang, while I stared straight ahead, not daring to turn around for fear of breaking the spell. When at last everyone sat down, Mama's eyes, Betsie's, and mine were brimming with tears.

At first we hoped it was the beginning of Mama's recovery. But the words she had sung she was not able to say, nor did she ever sing again. It had been an isolated moment, a gift to us from God, His own very special wedding present. Four weeks later, asleep with a smile on her lips, Mama slipped away from us forever.

I

T WAS IN

late November that year that a common cold made a big difference. Betsie began to sniff and sneeze, and Father decided that she must not sit behind the cashier's table where the shop door let in the raw winter air.

But Christmas was coming, the shop's busiest time: with Betsie bundled up in bed, I took to running down to the shop as often as I could to wait on customers and wrap packages and save Father clambering up and down from his tall workbench a dozen times an hour.

Tante Anna insisted she could cook and look after Betsie. And so I settled in behind Betsie's table, writing down sales and repair charges, recording cash spent for parts and supplies, and leafing through past records in growing disbelief.

Butâthere was no system here anywhere! No way to tell whether a bill had been paid or not, whether the price we were asking was high or low, no way in fact to tell if we were making money or losing it.

I hurried down the street to the bookseller one wintry afternoon, bought a whole new set of ledgers, and started in to impose method on madness. Many nights after the door was locked and the shutters closed, I sat on in the flickering gaslight, poring over old inventories and wholesalers' statements.

Or I would question Father. “How much did you charge Mr. Hoek for that repair work last month?”

Father would look at me blankly. “Why . . . ah . . . my dear . . . I can't really . . .”

“It was a Vacheron, Father, an old one. You had to send all the way to Switzerland for the parts and here's their bill andâ”

His face lit up. “Of course I remember! A beautiful watch, Corrie! A joy to work on. Very old, only he'd let dust get into it. A fine watch must be kept clean, my dear!”

“But how much did you charge, Father?”

I developed a system of billing and, increasingly, my columns of figures began to correspond to actual transactions. And increasingly, I discovered that I loved it. I had always felt happy in this little shop with its tiny voices and shelves of small shining faces. But now I discovered that I liked the business side of it too, liked catalogues and stock listings, liked the whole busy, energetic world of trade.

Every now and then when I remembered that Betsie's cold had settled in her chest and threatened, as hers always did, to turn into pneumonia, I would reproach myself for being anything but distressed at the present arrangement. And at night when I would hear the hard, racking cough from her bedroom below I would pray with all my heart for her to be better at once.

And then one evening two days before Christmas, when I had closed up the shop for the night and was locking the hallway door, Betsie came bursting in from the alley with her arms full of flowers. Her eyes when she saw me there were like a guilty child's.

“For Christmas, Corrie!” she pleaded. “We have to have flowers for Christmas!”

“Betsie ten Boom!” I exploded. “How long has this been going on? No wonder you're not getting better!”

“I've stayed in bed most of the time, honestlyâ” she stopped while great coughs shook her. “I've only got up for really important things.”

I put her to bed and then prowled the rooms with new-opened eyes, looking for Betsie's “important things.” How little I had really noticed about the house! Betsie had wrought changes everywhere. I marched back up to her room and confronted her with the evidence. “Was it important, Betsie, to rearrange all the dishes in the corner cupboard?”

She looked up at me and her face went red. “Yes it was,” she said defiantly. “You just put them in any old way.”

“And the door to Tante Jans's rooms? Someone's been using paint remover on it, and sandpaper tooâand that's hard work!”

“But there's beautiful wood underneath, I just know it! For years I've wanted to get that old varnish off and see. Oh Corrie,” she said, her voice suddenly small and contrite, “I know it's horrid and selfish of me when you've had to be in the shop day after day. And I will take better care of myself so you won't have to do it much longer; but, oh, it's been so glorious being here all day, pretending I was in charge, you know, planning what I'd do. . . .”

And so it was out. We had divided the work backwards. It was astonishing, once we'd made the swap, how well everything went. The house had been clean under my care; under Betsie's it glowed. She saw beauty in wood, in pattern, in color, and helped us to see it too. The small food budget which had barely survived my visits to the butcher and disappeared altogether at the bakery, stretched under Betsie's management to include all kinds of delicious things that had never been on our table before. “Just wait till you see what's for dessert this noon!” she'd tell us at the breakfast table, and all morning in the shop the question would shimmer in the back of our minds.

The soup kettle and the coffee pot on the back of the stove, which I never seemed to find time for, were simmering again the first week Betsie took over, and soon a stream of postmen and police, derelict old men and shivering young errand boys were pausing inside our alley door to stamp their feet and cup their hands around hot mugs, just as they'd done when Mama was in charge.

And meanwhile, in the shop, I was finding a joy in work that I'd never dreamed of. I soon knew that I wanted to do more than wait on customers and keep the accounts. I wanted to learn watch repair itself.

Father eagerly took on the job of teaching me. I eventually learned the moving and stationary parts, the chemistry of oils and solutions, tool and grindwheel and magnifying techniques. But Father's patience, his almost mystic rapport with the harmonies of watchworks, these were not things that could be taught.

Wristwatches had become fashionable and I enrolled in a school that specialized in this kind of work. Three years after Mama's death, I became the first licensed woman watchmaker in Holland.

And so was established the pattern our lives were to follow for over twenty years. When Father had put the Bible back on its shelf after breakfast, he and I would go down the stairs to the shop while Betsie stirred the soup pot and plotted magic with three potatoes and a pound of mutton. With my eyes on income-and-outlay, the shop was doing better and soon we were able to hire a saleslady to preside over the front room while Father and I worked in back.

There was a constant procession through this little back room. Sometimes it was a customer; most often it was simply a visitorâfrom a laborer with wooden

klompen

on his feet to a fleet ownerâall bringing their problems to Father. Quite unabashedly, in the sight of customers in the front room and the employees working with us, he would bow his head and pray for the answer.

He prayed over the work, too. There weren't many repair problems he hadn't encountered. But occasionally one would come along that baffled even him. And then I would hear him say: “Lord, You turn the wheels of the galaxies. You know what makes the planets spin and You know what makes this watch run. . . .”

The specifics of the prayer were always different, for Fatherâwho loved scienceâwas an avid reader of a dozen university journals. Through the years he took his stopped watches to “the One who set the atoms dancing,” or “who keeps the great currents circling through the sea.” The answers to these prayers seemed often to come in the middle of the night: many mornings I would climb onto my stool to find the watch that we had left in a hundred despairing pieces fitted together and ticking merrily.

The Ten Booms with several of their foster children. Corrie is on left, Father on right, and Betsie in front.

One thing in the shop I never learned to do as well as Betsie, and that was to care about each person who stepped through the door. Often when a customer entered, I would slip out the rear door and up to Betsie in the kitchen. “Betsie! Who is the woman with the Alpina lapel-watch on a blue velvet bandâstout, around fifty?”

“That's Mrs. van den Keukel. Her brother came back from Indonesia with malaria and she's been nursing him. Corrie,” as I sped back down the stairs, “ask her how Mrs. Rinker's baby is!”

And Mrs. van den Keukel, leaving the shop a few minutes later, would comment mistakenly to her husband, “That Corrie ten Boom is just like her sister!”