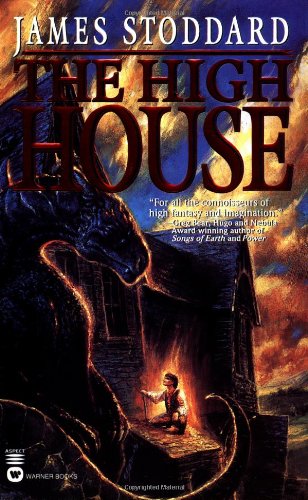

The High House

THE HIGH HOUSE

James Stoddard

Book One Of The

Evenmere Chronicles

Other Books by James Stoddard

THE FALSE HOUSE

EVENMERE

THE NIGHT LAND, A STORY RETOLD

This is a work of fiction. All events portrayed in this book are fictitious, and any resemblance to real people or events is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 1998 by James Stoddard. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or portions thereof, in any form.

Visit www.tinyurl.com/james-stoddard to learn more about the author

To contact James Stoddard send email to: [email protected]

Cover illustration and design by Scott Faris at www.fariswheel.com

A Ransom Book

Printed in the United States of America

First Printing: July 2015 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

FOR KATHRYN

FOR EVER

- Author’s Note

- Maps

- The High House

- Return

- The Tigers of Naleewuath

- Beseiged

- The Secret Ways

- The Path To The Towers

- The Clock Tower

- Captured

- Kitinthim

- Veth

- Beside the Rainbow Sea

- Innman Tor

- Evasions

- The Room Of Horrors

- The Angel

Author’s Note

Besides being a Story of Adventure this book was written as a tribute to Lin Carter and the “Sign of the Unicorn” fantasy series that he edited from 1969 to 1974. It is hoped that those who recognize herein references to countries chronicled by others will take it for the homage intended. As for myself, having been to neither New York nor Narnia, I must give equal credence to both.

“… all the doors you had yet seen … were doors in; here you came upon a door out. The strange thing to you … will be, that the more doors you go out of, the farther you get in.” —

Lilith

by George MacDonald

The High House

The High House, Evenmere, that lifts its gabled roofs among tall hills overlooking a country of ivy and hawthorn and blackberries sweet but small as the end of a child’s finger, has seldom been seen by ordinary men. Those who come there do so not by chance, and those who dwell there abide long within its dark halls, seldom venturing down the twisting road to the habitations of men. Of all who have lived there, one was born and raised beneath its banners, the man named Carter Anderson, who left not of his own accord, and was summoned back in its time of need. His life and the great deeds he did during the Great War of the High House is told of in

The Gray Book of Evenmere

, but this is a story from long before his days of valor.

He was born in the Lilac Room, where sunlight, diffused between guards of ivy, wafted through the three tall windows, brightening their rich mahogany moldings, casting leaf patterns on the red woven quilt and the dusky timber at the foot of the cherry-wood sleigh bed. The doctor pronounced him a “splendid lad,” and his father, waiting beyond the door, smiled and eased his pacing at the noise of his wailing cry.

He remembered his mother only as warmth and love, and slender, dark beauty, for she died when he was five, and he wept many days upon the red quilt in the Lilac Room. Lord Ashton Anderson, his father, the Master of the house, quit his slow laughter after that, and was often gone many days at a time, returning with mud on his boots and shadowed circles around his pale blue eyes.

So Carter grew up, an only child, a lonely boy in the great house, his companions the servants of the manor. Of these, he had three favorites: there was Brittle, the butler, a taciturn man, tall and thin, quite ancient, but still limber; and Enoch, the Master Windkeep, whose sole job was to wind the many clocks throughout the house. Enoch was the companion Carter loved best, ancient as a giant oak and nearly as tanned, older than Brittle even, but burly of frame and jovial by nature, with hair still jet black, set in tiny ringlets like an Assyrian. The boy often accompanied him on his rounds through the entrance hall, the dining room, the library, the picture gallery, the drawing room, the morning room, and then to the servants’ block to wind the clocks in the kitchen court, the servants’ hall, the housekeeper’s room, the back of the men’s corridor, and at the very top of a cherry alcove on the women’s stair, where hung a little cuckoo with a tiny yellow wren. After that, they went up the gentlemen’s stair to the bedrooms, the private library and others, then on to the sleeping quarters on the third floor.

But on the days when Enoch took the door leading from the top of the third story up to what he called “the Towers,” Carter was not allowed to accompany him. The boy hated those times, for the Windkeep would be gone many days, and Carter always imagined him climbing a long thin stair, open on either side, with the stars to his left hand and his right, and he ascending past them to the Towers, which surely lay that far if he must be gone so long.

The final companion of the three was the Lamp-lighter, whose name was Chant. He had a boyish face and a boyish smile, though the gray at his temples bespoke middle age. A bit of the gentle rogue lay upon him, and his eyes were rose-pink, which anyone other than Carter, who knew no different, might have thought bizarre. He had poetry within him; as Lamp-lighter he lit the globes at what he called “the eight points of the compass,” and he quoted Stevenson, saying his duties consisted of “punching holes in the darkness.” Carter liked Chant, though sometimes his conversation was too complex and sometimes too cynical. He had an odd way of turning a corner on the outside of the house and suddenly vanishing. Carter followed many times, racing around to catch some trace of him, but he never did, so that the boy thought he must be marvelously fast. But magic was commonplace in the house, and Carter saw it often without recognizing it for what it was.

Because there were always rooms to rummage through, closets and crannies, galleries and hallways to explore, Carter grew up an imaginative, adventurous boy, full of curiosity. His father often entertained company during the times he was home, men not in frock coats and top hats, but in armor, or robes, or garb even more grand. There were seldom women, though once a tall, graceful lady came to the house dressed like a queen, all in pearls and white lace, who gave Carter beautiful smiles and patted him on the head, reminding him of his mother, so that his heart ached long after she had gone.

These visitors did not come for pleasure; that was always clear, and they seldom entered through the front door; mostly Brittle ushered them in from the library, as if they had stepped fresh from a book. They ate dinner on the oak dining table, and afterward Carter sat in his father’s lap at the head of the table and listened to them talk. They spoke of wars and disputes in far-off countries, of ravaging wolves and robbers. Although the lord was a soft-spoken man, and his chair no higher than the others around the table, they treated him as a king, and implored him to resolve their difficulties. And often, near the end of the evening, when Carter lay sleepy in his father’s lap, Lord Anderson said, “I will come.” Then Carter knew his father would put on his greatcoat the next day, and his tall hat, and Tawny Mantle, that he would buckle his strange sword around his waist, the one terraced like a lightning bolt, retrieve his marble-headed walking staff, and be gone many days.

One day, a week after Carter’s seventh birthday, it happened that he wandered perplexed in the drawing room, looking behind the gray stuffed sofa, crying softly, when his father entered the room.

“Here, now, what are these tears?” Lord Anderson asked, laying his hand on his son’s shoulder. He was a kind man, if often sad, and Carter had the greatest confidence in him.

“I’ve lost my red birthday ball.”

“Where did you last have it?”

“I don’t remember.”

His father thought a moment, then said, “Perhaps it is time to show you something. Come along.”

Hand in hand, they left the drawing room, through the transverse corridor to the tall oaken doors into the library, an endless expanse of bookcases where Carter had often lost his way. Lord Anderson did not walk between the rows of books, but took his son through the four-paneled door to the left, into a small study, which Carter did not recall ever having seen before. It was windowless, with a tall ceiling, and a blue carpet with gold fleur-de-lis. There were seven buttercup lights already burning in the brass candelabra, but these were scarcely needed because of the stained-glass skylight, a mosaic in red, blue, and gold depicting an angel presenting a large book to a somber man. The angel looked both beautiful and terrible at once; his long, golden hair flowed to his shoulders and his face was bright where the sun shone through it. A golden belt encircled the waist of his white robe, and the sword strapped upon it gave him a fierce, warrior look. Carter liked him immediately.

The study was furnished only with a kidney-shaped desk, having a leather top fastened with brass hobnails and a matching dark leather chair. Mahogany panels decorated the walls, a fireplace stood beside the door, and a bookcase with blue-leaded glass rested behind the desk. Unlocking the bookcase with a small skeleton key taken from the top drawer, Lord Anderson withdrew a heavy leather book lined with gold leaf. He set it upon the desk, sat himself in the leather chair, and bade his son climb into his lap. But he did not yet open the volume.

“This is the Book of Forgotten Things,” his father said gently, but with great reverence. “When you cannot find a thing, when you need to remember something you have forgotten, seek it here. Now open it.”

Carter slowly turned the pages. At first, the volume was blank, but to his delight, a picture arose and came to life at the sixth page, and he saw himself in his room holding his red ball. After playing with it a time, he kicked it under the bed and left.