The Hindus (59 page)

Authors: Wendy Doniger

The geographical divide is matched by a major linguistic shift, from Sanskrit and the North Indian vernaculars derived from it (Hindi, Bangla, Marathi, and so forth) to Tamil (a Dravidian language, from a family entirely separate from the Indo-European group) and its South Indian cousins, such as Telugu in Andhra, Kannada in Mysore, and Malayalam in Kerala. Although we have no surviving literature in Tamil until anthologies made in the sixth century CE, other forms of evidence tell us a great deal about a thriving culture in South India, much of it carried on in Tamil, from at least the time of Ashoka, in the third century BCE. As with Sanskrit and the North Indian vernaculars, Tamil was the language of royal decrees and poetry for many centuries before texts in Kannada, Telugu, and Malayalam began to be preserved.

Tamil as a literary language appears to have developed from traditions separate from those of Sanskrit. The inscriptions in Tamil dedications of caves were written in a form of Tamil Brahmi script, probably brought not south from the Mauryan kingdom but north from Sri Lanka.

14

The earliest extant Tamil texts are anthologies of roughly twenty-three hundred short poems probably composed by the early centuries of the Common Era, then anthologized under the Pandyas and later reanthologized under the Cholas in the ninth to thirteenth century.

15

The poems are known in their totality as Cankam (“assembly”) poetry, named after a series of three legendary assemblies said to have lasted for a total of 9,990 years long, long ago. The sea is said to have destroyed the cities where the first two assemblies were held, yet another variant of that most malleable of myths, the legend of the flood. “Cankam” is the Tamil transcription of the Sanskrit /Pali word

sangham

(“assembly”) and may have been applied to this literature as an afterthought, as a Hindu response to the challenge of Buddhists and Jainas, who termed their own communities

sanghams

. The Cankam anthologies demonstrate an awareness of Sanskrit literature (particularly the

Mahabharata

and

Ramayana

), of the Nandas and Mauryas, and of Buddhists and Jainas.

14

The earliest extant Tamil texts are anthologies of roughly twenty-three hundred short poems probably composed by the early centuries of the Common Era, then anthologized under the Pandyas and later reanthologized under the Cholas in the ninth to thirteenth century.

15

The poems are known in their totality as Cankam (“assembly”) poetry, named after a series of three legendary assemblies said to have lasted for a total of 9,990 years long, long ago. The sea is said to have destroyed the cities where the first two assemblies were held, yet another variant of that most malleable of myths, the legend of the flood. “Cankam” is the Tamil transcription of the Sanskrit /Pali word

sangham

(“assembly”) and may have been applied to this literature as an afterthought, as a Hindu response to the challenge of Buddhists and Jainas, who termed their own communities

sanghams

. The Cankam anthologies demonstrate an awareness of Sanskrit literature (particularly the

Mahabharata

and

Ramayana

), of the Nandas and Mauryas, and of Buddhists and Jainas.

Brahmins who settled in the South when kingdoms were first established there gradually introduced Sanskrit into the local language and in return learned not only Tamil words but Tamil deities and rituals and much else.

16

This two-way process meant that Tamil forms of religious sentiment moved into Sanskrit (which had had Dravidian loanwords already from the time of the

Rig Veda

) and went north. The Sanskrit Puranas (compendiums of myth and history) arose in the context of the development of kingdoms in the Deccan—Chalukyas and Pallavas in particular.

17

The Tamil “local Puranas” (

sthala puranas

) both echoed the Sanskritic forms and contributed to the contents of the

Bhagavata Purana

, composed in South India.

16

This two-way process meant that Tamil forms of religious sentiment moved into Sanskrit (which had had Dravidian loanwords already from the time of the

Rig Veda

) and went north. The Sanskrit Puranas (compendiums of myth and history) arose in the context of the development of kingdoms in the Deccan—Chalukyas and Pallavas in particular.

17

The Tamil “local Puranas” (

sthala puranas

) both echoed the Sanskritic forms and contributed to the contents of the

Bhagavata Purana

, composed in South India.

A few of the Cankam poems are already devoted to religious subjects, singing the praise of Tirumal (Vishnu) and the river goddess Vaikai, or of Murukan, the Tamil god who had by now coalesced with the northern god Skanda, son of Shiva and Parvati. But the overwhelming majority of these first Tamil poems were devoted to two great secular themes, contrasting the intimate emotions of love, the “inner” (

akam

) world, with the virile public world of politics and war, the “outer” (

puram

) world. The poems that praised kings and heroes in the

puram

genre were the basis of later hymns in praise of the gods.

akam

) world, with the virile public world of politics and war, the “outer” (

puram

) world. The poems that praised kings and heroes in the

puram

genre were the basis of later hymns in praise of the gods.

The

akam

poems used geographical landscapes, peopled by animals and characterized by particular flowers, to map the five major interior landscapes of the emotions: love in union (mountains, with monkeys, elephants, horses, and bulls); patiently waiting for a wife (forest and pasture, with deer), anger at infidelity (river valley, with storks, herons, buffalo); anxiously waiting for the beloved (seashore, with seagulls, crocodiles, sharks); separation (desert waste-land, with vultures, starving elephants, tigers, wolves).

18

Akam

poetry also distinguished seven types of love, of which the first is unrequited love and the last is mismatched love (when the object of desire is too far above the one who desires). The bhakti poets took these secular themes, particularly those involving what Sanskrit poetry called “love in separation” (

viraha

), and reworked them to express the theological anguish of the devotee who is separated from the otiose god, not because the god does not love him in return but because the god is apparently occupied elsewhere.

gv

The assumption seems to be that of the old blues refrain “How can I miss you if you never go away?”

akam

poems used geographical landscapes, peopled by animals and characterized by particular flowers, to map the five major interior landscapes of the emotions: love in union (mountains, with monkeys, elephants, horses, and bulls); patiently waiting for a wife (forest and pasture, with deer), anger at infidelity (river valley, with storks, herons, buffalo); anxiously waiting for the beloved (seashore, with seagulls, crocodiles, sharks); separation (desert waste-land, with vultures, starving elephants, tigers, wolves).

18

Akam

poetry also distinguished seven types of love, of which the first is unrequited love and the last is mismatched love (when the object of desire is too far above the one who desires). The bhakti poets took these secular themes, particularly those involving what Sanskrit poetry called “love in separation” (

viraha

), and reworked them to express the theological anguish of the devotee who is separated from the otiose god, not because the god does not love him in return but because the god is apparently occupied elsewhere.

gv

The assumption seems to be that of the old blues refrain “How can I miss you if you never go away?”

Beginning in about 600 CE, the wandering poets and saints devoted to Shiva (the Nayanmars,

gw

traditionally said to number sixty-three) and to Krishna-Vishnu (the twelve Alvars) sang poems in the devotional mode of bhakti. The group of Nayanmars known as the first three (Appar, Campantar, and Cuntarar, sixth to eighth century) formed the collection called the

Tevaram

,

19

which departed from the Cankam style in using a very different Tamil grammar. Nammalvar (“Our Alvar”), the last of the great Alvars, writing in the ninth century, called his work “the sacred spoken word” (

tiruvaymoli

), and Manikkavacakar (late ninth century) called his Shaiva text “the sacred speech” (

Tiruvacakam

).

20

These works were clearly meant to be performed orally, recited, and since the tenth century they have been performed, both in homes and in temples.

gw

traditionally said to number sixty-three) and to Krishna-Vishnu (the twelve Alvars) sang poems in the devotional mode of bhakti. The group of Nayanmars known as the first three (Appar, Campantar, and Cuntarar, sixth to eighth century) formed the collection called the

Tevaram

,

19

which departed from the Cankam style in using a very different Tamil grammar. Nammalvar (“Our Alvar”), the last of the great Alvars, writing in the ninth century, called his work “the sacred spoken word” (

tiruvaymoli

), and Manikkavacakar (late ninth century) called his Shaiva text “the sacred speech” (

Tiruvacakam

).

20

These works were clearly meant to be performed orally, recited, and since the tenth century they have been performed, both in homes and in temples.

Bhakti in the sense of supreme devotion to a god, Shiva, and even to the guru as god, appeared in the

Shvetashvatara Upanishad

(6.23). Ekalavya in the

Mahabharata

demonstrates a kind of primitive bhakti: great devotion to the guru and physical self-violence. The concept of bhakti was further developed in the

Ramayana

and the

Gita

, which established devotion as a third alternative to ritual action and knowledge. But South Indian bhakti ratchets up the emotion from the

Gita

, so that even a direct quotation from the

Gita

takes on an entirely different meaning in the new context, as basic words like

karma

and

bhakti

shift their connotations.

Shvetashvatara Upanishad

(6.23). Ekalavya in the

Mahabharata

demonstrates a kind of primitive bhakti: great devotion to the guru and physical self-violence. The concept of bhakti was further developed in the

Ramayana

and the

Gita

, which established devotion as a third alternative to ritual action and knowledge. But South Indian bhakti ratchets up the emotion from the

Gita

, so that even a direct quotation from the

Gita

takes on an entirely different meaning in the new context, as basic words like

karma

and

bhakti

shift their connotations.

The Tamils had words for bhakti (such as

anpu

and

parru

), though eventually they also came to use the Sanskrit term (which became

patti

in Tamil). But the Tamil poets transformed the concept of bhakti not only by applying it to the local traditions of the miraculous exploits of local saints but by infusing it with a more personal confrontation, an insistence on actual physical and visual presence, a passionate transference and countertransference. A typically intimate and rural note is evident in the Alvars’ retelling of the legend in the Valmiki

Ramayana

about a squirrel who assisted Rama in building the bridge to Lanka to rescue Sita; the Alvars add that in gratitude for this assistance, Rama touched the squirrel and imprinted on it the three marks visible on all Indian squirrels today.

gx

21

The emotional involvement, the pity, desire, and compassion of the bhakti gods causes them to forget that they are above it all, as metaphysics demands, and reduces them to the human level, as mythology demands.

anpu

and

parru

), though eventually they also came to use the Sanskrit term (which became

patti

in Tamil). But the Tamil poets transformed the concept of bhakti not only by applying it to the local traditions of the miraculous exploits of local saints but by infusing it with a more personal confrontation, an insistence on actual physical and visual presence, a passionate transference and countertransference. A typically intimate and rural note is evident in the Alvars’ retelling of the legend in the Valmiki

Ramayana

about a squirrel who assisted Rama in building the bridge to Lanka to rescue Sita; the Alvars add that in gratitude for this assistance, Rama touched the squirrel and imprinted on it the three marks visible on all Indian squirrels today.

gx

21

The emotional involvement, the pity, desire, and compassion of the bhakti gods causes them to forget that they are above it all, as metaphysics demands, and reduces them to the human level, as mythology demands.

Despite its royal and literary roots, bhakti is also a folk and oral phenomenon. Many of the bhakti poems were based on oral compositions, some probably even by illiterate saints.

22

Both Shaiva and Vaishnava bhakti movements incorporated folk religion and folk song into what was already a rich mix of Vedic and Upanishadic concepts, mythologies, Buddhism, Jainism, conventions of Tamil and Sanskrit poetry, and early Tamil conceptions of love, service, women, and kings,

23

to which after a while they added elements of Islam. This cultural bricolage is the rule rather than the exception in India, but the South Indian use of it is particularly diverse. As A. K. Ramanujan and Norman Cutler put it, “Past traditions and borrowings are thus re-worked into bhakti; they become materials, signifiers for a new signification, as a bicycle seat becomes a bull’s head in Picasso. Often the listener/reader moves between the original material and the work before him—the double vision is part of the poetic effect.”

24

This too was a two-way street, for just as Picasso imagined someone in need of a bicycle seat using his bull’s head for that purpose,

25

so the new bhakti images also filtered back into other traditions, including Sanskrit traditions.

22

Both Shaiva and Vaishnava bhakti movements incorporated folk religion and folk song into what was already a rich mix of Vedic and Upanishadic concepts, mythologies, Buddhism, Jainism, conventions of Tamil and Sanskrit poetry, and early Tamil conceptions of love, service, women, and kings,

23

to which after a while they added elements of Islam. This cultural bricolage is the rule rather than the exception in India, but the South Indian use of it is particularly diverse. As A. K. Ramanujan and Norman Cutler put it, “Past traditions and borrowings are thus re-worked into bhakti; they become materials, signifiers for a new signification, as a bicycle seat becomes a bull’s head in Picasso. Often the listener/reader moves between the original material and the work before him—the double vision is part of the poetic effect.”

24

This too was a two-way street, for just as Picasso imagined someone in need of a bicycle seat using his bull’s head for that purpose,

25

so the new bhakti images also filtered back into other traditions, including Sanskrit traditions.

Unlike most Sanskrit authors and Cankam poets, the bhakti poets revealed details of their own lives and personalities in their texts, so that the voice of the saint is heard in the poems. The older myths take on new dimensions in the poetry: “What happens to someone else in a mythic scenario happens to the speaker in the poem.”

26

And so we encounter now the use of the first person, a new literary register. It is not entirely unprecedented; we heard some voices, even women’s voices (such as Apala’s), in direct speech in the

Rig Veda

, and a moment in the

Mahabharata

when the narrator breaks through and reminds the reader, “ I have already told you” (about Yudhishthira’s dog). But the first person comes into its own in a major way in Cankam poetry and thence in South Indian bhakti.

SECTARIAN DIVERSITY IN SOUTH INDIAN TEMPLES26

And so we encounter now the use of the first person, a new literary register. It is not entirely unprecedented; we heard some voices, even women’s voices (such as Apala’s), in direct speech in the

Rig Veda

, and a moment in the

Mahabharata

when the narrator breaks through and reminds the reader, “ I have already told you” (about Yudhishthira’s dog). But the first person comes into its own in a major way in Cankam poetry and thence in South Indian bhakti.

The growth of bhakti is intimately connected with the burgeoning of sectarian temples. We have seen textual evidence of the growth of sectarianism in the

Mahabharata

and

Ramayana

period, supported by epigraphs and references to temples in texts such as the

Kama-sutra

and the

Artha-shastra

. We have noted the cave temples of Bhaja, Karle, Nasik, Ajanta, and Ellora. And we will soon encounter the sixth-century Vishnu temple in Deogarh in Rajasthan, and other Gupta temples at Aihole, Badami, and Pattadakal. Now is the moment to consider the first substantial

groups

of temples that we can see in the flesh, as it were, in South India, for under the Pallavas, temples began to grow into temple cities.

Mahabharata

and

Ramayana

period, supported by epigraphs and references to temples in texts such as the

Kama-sutra

and the

Artha-shastra

. We have noted the cave temples of Bhaja, Karle, Nasik, Ajanta, and Ellora. And we will soon encounter the sixth-century Vishnu temple in Deogarh in Rajasthan, and other Gupta temples at Aihole, Badami, and Pattadakal. Now is the moment to consider the first substantial

groups

of temples that we can see in the flesh, as it were, in South India, for under the Pallavas, temples began to grow into temple cities.

Building temples may have been, in part, a response to the widespread Buddhist practice of building stupas or to the Jaina and Buddhist veneration of statues of enlightened figures. Hindus vied with Buddhists in competitive fund-raising, and financing temples or stupas became a bone of contention. One temple at Aihole, dedicated to a Jaina saint, has an inscription dated 636, which marks this as one of the earliest dated temples in India.

27

The Pallavas supported Buddhists, Jainas, and Brahmins and were patrons of music, painting, and literature. Many craftsmen who had worked on the caves at Ajanta, in the north, emigrated southward to meet the growing demand for Hindu art and architecture in the Tamil kingdoms.

28

27

The Pallavas supported Buddhists, Jainas, and Brahmins and were patrons of music, painting, and literature. Many craftsmen who had worked on the caves at Ajanta, in the north, emigrated southward to meet the growing demand for Hindu art and architecture in the Tamil kingdoms.

28

Narasimha Varman I (630-638), also known as Mahamalla or Mamalla (“great wrestler”), began the great temple complex at Mamallapuram that was named after him (it was also called Mahabalipuram); several other Pallavas probably completed it, over an extended period. At Mamallapuram, there is a free-standing Shaiva Shore Temple, a cave of Vishnu in his boar incarnation, an image of Durga slaying the buffalo demon, and five magnificent temples, called chariots (

raths

), all hewn from a single giant stone.

gy

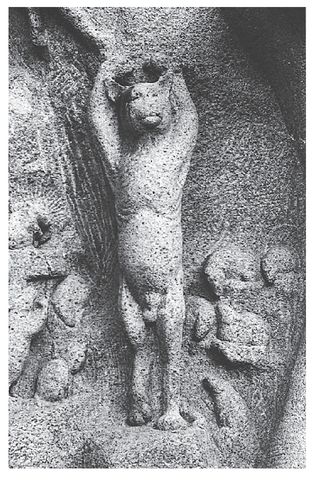

There is also an enormous bas-relief on a sculpted cliff, almost one hundred feet wide and fifty feet high, facing the ocean. The focus of the whole scene is a vertical cleft, in the center, through which a river cascades down, with half cobra figures (Nagas and Naginis) as well as a natural cobra in the midst of it. There are also lots of terrific elephants, deer, and monkeys, all joyously racing toward the descending river. (Real water may have flowed through the cleft at one time.) Sectarian diversity within Hinduism (as Indra and Soma and the Vedic gods were being shoved aside in favor of Vishnu, Shiva, and the goddess) is demonstrated by the dedication of different shrines to different deities and, within the great frieze, by the depiction of both an image of Shiva and a shrine to Vishnu. The frieze also contains a satire on ascetic hypocrisy: The figure of a cat stands in a yogic pose, surrounded by mice, one of whom has joined his tiny paws in adoration of the cat; Sanskrit literature tells of a cat who pretended to be a vegetarian ascetic and ate the mice until one day, noting their dwindling numbers, they discovered mouse bones in the cat’s feces.

29

raths

), all hewn from a single giant stone.

gy

There is also an enormous bas-relief on a sculpted cliff, almost one hundred feet wide and fifty feet high, facing the ocean. The focus of the whole scene is a vertical cleft, in the center, through which a river cascades down, with half cobra figures (Nagas and Naginis) as well as a natural cobra in the midst of it. There are also lots of terrific elephants, deer, and monkeys, all joyously racing toward the descending river. (Real water may have flowed through the cleft at one time.) Sectarian diversity within Hinduism (as Indra and Soma and the Vedic gods were being shoved aside in favor of Vishnu, Shiva, and the goddess) is demonstrated by the dedication of different shrines to different deities and, within the great frieze, by the depiction of both an image of Shiva and a shrine to Vishnu. The frieze also contains a satire on ascetic hypocrisy: The figure of a cat stands in a yogic pose, surrounded by mice, one of whom has joined his tiny paws in adoration of the cat; Sanskrit literature tells of a cat who pretended to be a vegetarian ascetic and ate the mice until one day, noting their dwindling numbers, they discovered mouse bones in the cat’s feces.

29

Other books

The Notorious Lord Havergal by Joan Smith

Crowned and Moldering by Kate Carlisle

Catching Preeya (Paradise South Book 3) by Rissa Brahm

Her Destiny by Monica Murphy

Suddenly Texan by Victoria Chancellor

Yesterday by C. K. Kelly Martin

Carnal Vengeance by Marilyn Campbell

Kelong Kings: Confessions of the world's most prolific match-fixer by Wilson Raj Perumal, Alessandro Righi, Emanuele Piano

Krampus: The Three Sisters (The Krampus Chronicles Book 1) by Halbach, Sonia