The History Buff's Guide to World War II (9 page)

Read The History Buff's Guide to World War II Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

5. GERMAN DECLARATION OF WAR ON THE UNITED STATES (DECEMBER 11, 1941)

It was not his brightest act. Days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hitler declared war on the United States, greatly simplifying U.S. entry into a European war.

The declaration was brief, less than a page long, and was clearly written without Hitler’s direct input. Emphasis was on high-seas law, about which he knew very little. The text stated, “Vessels of the American Navy, since early September 1941, have systematically attacked German naval forces…Germany for her part has always strictly observed the rules of international law in her dealings with the United States throughout the present war.”

14

Though Hitler underestimated the military and industrial potential of the United States and overestimated Japan’s chances of keeping American forces in the Pacific, he was not eager to invite yet another enemy into the fray. For years he had privately stated his desire to keep the United States out of the war. His ideal scenario involved Japan attacking the Soviet Union, with the Americans staying neutral. Yet instead of having a two-front war against Stalin, Hitler unilaterally created one against himself.

In his speech to the Reichstag announcing Germany’s declaration of war on the United States, Hitler stated, “A historical revision on a unique scale has been imposed on us by the Creator.”

6. WANNSEE CONFERENCE (JANUARY 20, 1942)

Nazi persecution of the Jews had not been systematic up to 1942. Officials initially expelled Jews from homes, businesses, and cities in an attempt to make areas “Jew free.” Emigration was also encouraged. By 1940, nearly half of Germany’s 500,000 Jews had left for Britain, the United States, Palestine, and elsewhere.

When the Reich overran areas with large “non-Aryan” populations, the solution was to contain the Jews in ghettos, often denying them food. Privation began to kill hundreds, then thousands, but the method was imprecise and slow. In the invasion of the Soviet Union, the Germans initiated use of Einsatzgruppen, or “Special Groups,” roaming death squads that liquidated Jews by mass shootings. By the end of 1941, at least one million Jews had died, yet no systematic plan for annihilation was yet in place.

Then Adolf Eichmann, head of Germany’s Race and Resettlement Office, called an assembly of fifteen administrators to the wealthy Berlin suburb of Wannsee. Their task was to coordinate a “final solution” to the Jewish problem.

In less than two hours, the officials outlined a new program, whereby Europe’s Jews would be collected and transported to special sites in the east, under the pretense that they were to be used as forced labor. Meeting minutes contained no references to killing, but the “laborers” were to include infants and the elderly. Destination points were a select few concentration camps, which were at that moment being fitted with gas chambers.

15

Wannsee was the first instance where genocide became official Nazi policy. Documentation from the conference stands as the most damning evidence to date that the Holocaust had been directed by the highest levels of the Third Reich. By all indications, the procedure was effectively implemented. Half of all Jews killed in the Holocaust died in a handful of death camps.

16

Among the potential “labor pools” cited in the Wannsee briefing minutes was Great Britain, with an estimated 330,000 Jews.

7. “UNCONDITIONAL SURRENDER”: THE CASABLANCA CONFERENCE (JANUARY 14–24, 1943)

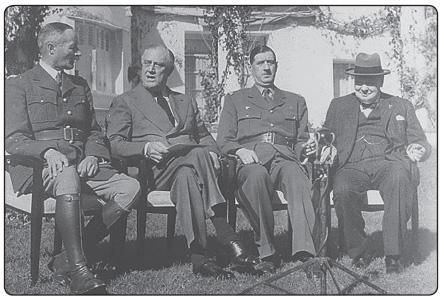

On the last day of a long summit, Roosevelt and Churchill were holding a press conference in sunny Casablanca. Stalin declined to attend the summit, wanting instead to monitor events at S

TALINGRAD

. The president and prime minister were reviewing the high-level issues of their meetings, such as the need for a unified French resistance. A photo op captured the proud but politically dim Gen. Henri Giraud (whom Churchill and Roosevelt tolerated) shaking the hand of ego-maniacal Gen. Charles de Gaulle (whom they loathed), suggesting that the French problem had been solved. It hadn’t.

The rest of the conference had gone generally well. The United States agreed to join Britain in a combined bomber offensive on German targets and affirmed its “Germany First” commitment. The British tacitly agreed to a cross-channel attack sometime in 1944.

As the press conference was about to conclude, Roosevelt uttered a phrase that took Churchill and journalists by surprise. He began to speak of Civil War icon Ulysses S. Grant and his famous nickname, “and the next thing I knew,” Roosevelt later recalled, “I had said it.”

17

Unconditional surrender. No peace talks. No negotiating.

At Casablanca, Roosevelt and Churchill also tried to unite French forces under Henri Giraud (far left) with Charles de Gaulle (second from right).

A popular myth emerged that the president’s statement was a slip of the tongue, that he neither desired it as a war aim nor discussed the idea with others. In reality, Roosevelt’s and Churchill’s cabinets had already debated the issue and agreed to it. But Roosevelt gave the prime minister no warning that he was going to unveil the policy at that time.

18

From that day forward, a full fifteen months after the United States had joined in the war, the Allies had a finite, definable, and shared goal.

19

For unknown reasons, both Roosevelt and Churchill were extremely ill for a month after Casablanca.

8. THE TEHRAN CONFERENCE (NOVEMBER 28–DECEMBER 1, 1943)

It was the first conference of “the Big Three” and the first ever meeting between an American president and a Soviet leader. Topics were kept at a high level, with specifics to be laid out in future meetings. Stalin agreed to enter the war against Japan sometime after the war in Europe reached a favorable end. Roosevelt outlined an intent to retake Burma.

On points of contention, the odd man out was routinely Churchill. He failed to convince his associates of pulling Turkey into the war. He also argued unsuccessfully for a greater commitment to a Balkan campaign (similar to a plan he had espoused during World War I) or a renewed effort to reach Germany through Italy. On several occasions he recommended delaying the invasion of France beyond the target of mid-1944, fearing a replay of Dunkirk and D

IEPPE

. Roosevelt and Stalin were jointly opposed. And so went most of the meetings.

20

At Tehran, the Big Three—Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin—finalized plans for a two-front assault on Germany and the Soviet Union’s later commitment against Japan in the Pacific.

On his impression of Stalin, Roosevelt optimistically observed, “I believe that we are going to get along very well with him and the Russian people—very well indeed.” Churchill, sensing his less-than-equal status at the conference, equated the situation with being a “poor little English donkey” stuck between a Russian bear and an American buffalo.

21

Churchill hosted a lavish dinner on the third night of the conference, which happened to be his sixty-ninth birthday. When Stalin arrived, Churchill welcomed his guest with a warm greeting and an outstretched hand. Stalin ignored him.

9. THE YALTA CONFERENCE (FEBRUARY 4–11, 1945)

Roosevelt came to the Crimea with two goals in mind: to ensure the defeat of Japan and to create the foundation of a United Nations. Both objectives, he believed, required the Soviet Union.

Stalin again pledged to fight the Japanese Empire, committing the Red Army to attack Manchuria three months after peace in Europe. In exchange, the Soviet leader demanded the Kurile Islands and the southern half of Sakhalin Island. On the United Nations, Stalin agreed to Soviet participation, provided the Soviet Union had sixteen seats, one for each Soviet state plus the USSR as a whole. Roosevelt and Churchill talked him down to three.

All agreed that Germany and Austria would be divided, demilitarized, and de-Nazified. Stalin suggested taking cash reparations from Germany, which would be split among the Big Three. Remembering how reparations had ruined the Treaty of Versailles, Churchill rejected the idea.

Most of the conference was spent on Poland, its borders, and its government. Stalin had already installed a provisional government, one very sympathetic to Soviet interests. Yet he promised to uphold the Declaration of Liberated Europe, forged earlier at the Yalta conference, which guaranteed “the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live.”

22

Historians commonly consider the conference to be “Year Zero” of the cold war, when a visibly dying Roosevelt and a politically compromised Churchill naively gave in to a land-hungry Stalin. In reality, it was the high point of Allied cooperation, when all three participants were naive and optimistic, incapable of foreseeing how future events—namely the death of an enemy and the detonation of an atomic device—could destroy what Yalta had achieved.

23

The Big Three met for the last time at Yalta. Roosevelt had only two months to live. In four months, Churchill was out of power.

In the interest of security, transcripts from the Yalta Conference were not made public until 1947.

10. HITLER’S SUDDEN DEPARTURE (APRIL 30, 1945)

Undoubtedly, nothing united the Allies as much as Adolf Hitler. By striking fear among his rivals, the German Führer drove together devout ideological enemies. On April 30, 1945, that unifying force ceased to exist. Trapped in his Berlin bunker with the Red Army only blocks away, Hitler decided to take his own life, stating that he “preferred death to cowardly abdication or even capitulation.”

24

As time would prove, Hitler’s decision meant the end of Allied cooperation. Confirming the impact of the Führer, Germany became the epicenter of East-West hostilities for more than forty years. No other location was remotely as divisive—not Japan, not Italy, not even Poland—where a tacit gentlemen’s agreement assured Soviet domination. In blasting a hole through the back of his head, Hitler arguably fired the first shot of the cold war. “Now he’s done it, the bastard,” said Stalin upon hearing the news of the warlord’s suicide. “Too bad he could not have been taken alive.”

25

Fearing Hitler’s corpse would become a rallying point for future Nazi uprisings, the Soviets took his charred remains from the Berlin Chancellery garden on May 2, 1945, and secretly transported them to Moscow. The Soviet government waited until 1968 before admitting they had taken the body.