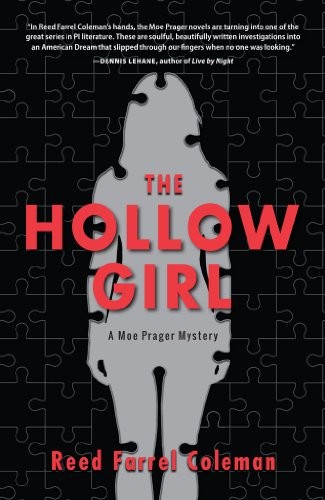

The Hollow Girl

Authors: Reed Farrel Coleman

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #General, #Hard-Boiled

A Moe Prager Mystery

Reed Farrel Coleman

F+W Media, Inc.

But always where she goes there is rain

.

—Kathleen Eull

… and the Hollow Girl knits her clothing out of self-loathing.

—anonymous fan

Prologue: 1993, Lenox Hill Hospital

1993, Lenox Hill Hospital

Nine years had passed since Israel Roth and I had placed pebbles atop Hannah Roth’s headstone. I didn’t know it then, but that day in the granite fields, on the crusted snow and icy paths, was goodbye. Husband was never coming back to see wife again. I couldn’t have known it then. Mr. Roth never said as much, but I had since learned to recognize goodbye. Goodbye has its own feel, its own flavor, a flavor as distinct as my mother’s burnt, over-percolated coffee. Sometimes the taste of it comes back to me, that black, god-awful goop that poured like syrup and had a viscosity and flavor more akin to unchanged motor oil than coffee. Sometimes, that’s what goodbye tastes like. Goodbye also has its own aroma, its own scent. Sometimes, like today, it smells like a hospital room.

“So, Mr. Moe, where are you?” Israel Roth asked, his voice weak and strained. “You seem far away.”

“Sorry, Izzy, I was time traveling.”

He smiled up at me. “I’m the one who’s dying, here. You think maybe I’m the one what should be entitled to going back in time?”

“I was thinking about my mother’s coffee. Trust me when I tell you you wouldn’t want to go back in time for that.”

“That bad, huh?”

“Worse. You know the saying about what doesn’t kill you only makes you stronger?”

“Sure.”

“By that measure, I should be Hercules.”

“You’re plenty strong, Mr. Moe. You shouldn’t fool yourself otherwise.” His eyesight almost gone, he blindly reached his hand out for me to take hold of. I noticed that the skin of his forearm was so loose that it folded over on itself, obscuring at last the numbers tattooed there.

I took his hand, squeezing too tightly. “I’ve never been very good at self-deception,” I said.

“It’s no gift, lying to yourself. I’m not so blind as you think, Moses.” He only ever called me that when he was serious. “You see the skin covers the numbers those bastards put on me like cattle. Not seeing it doesn’t fool me that it’s not there. Only when I am so many ashes, when I am dust and teeth and bits of bone, will I be free from that number. You know what, sometimes I think even then, when you scatter me to the wind, that I will be only a number.”

“Never to me, Mr. Roth. Never to me.”

He squeezed my hand back, but didn’t say a word. We sat there like that for a few minutes, his hand clutched in mine, both of us time traveling.

Goodbye, as Emily Dickinson might have said, has a certain slant of light. Maybe I was imagining it, but the angle of the afternoon light coming through the vertical slats of the blind seemed to whisper goodbye. I wasn’t ready for it, whispered or shouted. In Mr. Roth’s company was perhaps the only place I ever truly fit. When he was gone, where would that leave me? Where would I fit? Although I’d loved being on the job, the job never quite loved me back. Shit, most of the guys I worked with wouldn’t have known who Emily Dickinson was, or when she lived, or if she wrote, or what she wrote. None of them could have quoted a line of poetry if their lives depended on it. But their lives never depended on it. Has anybody’s life ever depended on such a flimsy thing? Only I knew about that slant of light. Only the college boy who had become a cop on a drunken bet.

Not even now, not after sixteen years away from the Six-O, did I feel like I ever quite fit in. I was always stuck somewhere in between, always apart from and a part of at the same time. Mr. Roth’s fate was at hand. I wondered if mine was to always be stuck above or beneath. Maybe that’s why I’d wanted my gold shield so fucking bad, to show that I fit in, that I was one of the guys. It was nonsense. I didn’t fit in any better in the wine business. If anything, it was worse. I never wanted any part of it. No gold shields in the wine business.

“So, Mr. Moe, where are you traveling now?” Izzy broke the silence, his hand clenching tighter still. “Back to Momma’s coffee?”

“No. I’m all over the place. I’ve never been able to live in the moment.”

“Such a stupid phrase, ‘in the moment’. It’s foolishness, no? When is the moment? Now is just the past in waiting. As soon as it’s here, it’s gone. You can’t live in a place that vanishes as soon as it comes. The present, Mr. Moe, is always coming and then always gone. Live for the future, and live in the past. There is only that.”

I opened my mouth to argue. No words came out. I wanted to think it was because Mr. Roth seemed to have drifted into sleep, but it wasn’t that at all. It was that the truth of what he’d said had knocked me silent. But whatever the nature of the relationship between past, present, and future, there was one inescapable fact: Israel Roth had very little future left. And when he was gone, a piece of me would go with him. Then, when his hand went suddenly slack, I knew that wherever that piece of me was going, it had just arrived. Mr. Roth was right: There is only future and past. Now is fleeting. Now is gone.

2013

Humpty Dumpty had nothing on me. No egg ever cracked so well, no window shattered into as many ragged pieces. Me, so hardened, so sure there was nothing new the nonexistent God could put on my plate. It galled me that in the end, my mother—think Nostradamus vis-à-vis Chicken Little—had been right. “When things are good,” she used to say, “watch out.” But I hadn’t watched out, because I had a new grandson. Because after surviving stomach cancer, and burying my childhood friend Bobby Friedman, and finally asking Pam to marry my sorry old ass, I’d stood high on a mountain of my own self-assuredness and waved my middle finger at the universe. It waved it right back.

Fuck you, Moe Prager. Fuck you!

If you need a lesson about the appalling lack of fairness in the universe, let me give it: I was still alive and Pam was not. I’d lost my folks, Katy, Mr. Roth, Rico Tripoli, Bobby, and a hundred other people from my past, but the grief those deaths had caused was a warm-April-sun-on-your-face-all-the-hotdogs-you-could-eat-on-opening-day-at-Citi-Field compared to this. Because with this came guilt, the gnawing guilt of

coulda done

and

shoulda done

. I hadn’t known guilt, not really, not until I heard the sirens, not until I looked out the window of my Sheepshead Bay condo and saw half of Pam’s body sticking out from beneath the front of a car, the poor girl who’d hit her sitting on the Emmons Avenue curb, arms folded around herself, rocking madly, wishing it would all just go away. I wanted to scream down at her that not all the mad rocking or self-comforting behavior in the world would make anything go away.

Guilt is like that, a permanent infection. Not chronic, permanent. The thing you’ve done to bruise the universe may fade, but the guilt never goes. Not really. Not ever. Oh sure, there are bad days and worse days, and you come to see the less bad days as good ones. That’s a lie. I wanted to scream down to the girl that the guilt was mine, not hers. That it was me who’d sent Pam down to get the

Sunday Times

. That I could have gone myself, should have gone myself. That my car was in its parking spot in back of my building, so that it wouldn’t have been a trade-off, my life for Pam’s. That I was nearly fully recovered, but that I’d grown old and lazy and used to people doing for me. I did not scream down to her or go down to her, not immediately. I don’t think I cried. I was frozen there in front of the window.

I wasn’t a forgetter. Even at my drunkest, I’d never blacked out. Like the rest of my life, that all changed the night Pam was crushed beneath the wheels of Holly D’Angelo’s new Jeep Wrangler, a high school graduation gift she had received that very June day. Sometimes I find myself thinking about Holly D’Angelo—a pretty neighborhood girl who kept saying “I’m so sorry, mister, I’m sorry”—and the gift of guilt that would keep on giving. I wanted to take her hurt away. I really did. We all fuck up. We all fall down. But we shouldn’t have to pay forever. Holly D’Angelo shouldn’t have to, anyway. That was for me to do, to pay.

I do remember that I was standing in front of the uniform from the Six-One Precinct, his face not a blur exactly—a blank, his face was more of a blank. I remember speaking to him, but looking back and forth between Pam’s motionless body and Holly D’Angelo’s endlessly rocking one. More than that, I don’t recall or don’t want to recall. The guilt, that’s another matter. There’s been no escape from that.

I was conscious of someone standing over me. For a brief second, I thought it was Pam. She was like that, getting up early, leaving me to sleep, making us some fancified breakfast that I’d barely touch, then she’d come to wake me. She wouldn’t kiss me, but rather lean down close so that I could feel her warm breath on my neck. Then she would brush the back of her hand against my cheek. Is there anything quite as subtly intimate as a lover’s touch on your cheek? In the depths of my illness, during the worst of the chemo, I swore it was Pam who willed me to live. I was too sick, too weak, too unhappy to have willed myself to do anything but surrender. And oh, how I wanted to surrender. How I longed to shut my eyes and have it all go away. Pam wasn’t having any of that.

She didn’t pretend that I was well, didn’t ignore my symptoms, but she also refused to treat me like a leper. When she was down visiting from Vermont between cases, she always shared my bed. Even at the lowest points, when I was bald and ashen and skeletal, when I couldn’t stand to look at myself in the mirror, when I reeked from coming death, Pam slept with me. Cancer is an isolating experience. You can’t imagine just how isolating. Treatment and recovery are worse, in their way. When I needed someone to keep me tethered to life, Pam kept me tethered.

Then that brief second ended and reality flooded back in. It wasn’t Pam standing over me. Pam was never going to stand over me again. I would never see her again. Never taste her again. Never feel the brush of her hand against my cheek again. Pam was gone. And gone was gone forever. The truth of that was hard enough to take, but it was the guilt the truth came wrapped in that made me close my eyes to the light, to the figure throwing shadows over my bed.

“Moses. Moses. Get up. Get up!”

“Go away,” I heard myself say, voice slurred and sandpapery. I was grabbed by the shoulders, yanked to a seated position, my head snapping forward. “You’ve got that wrong, bartender: I prefer to be stirred, not shaken.” I fell back onto my bed.

“Very funny, little brother. Get up.” It was Aaron.

“What time is it?”

“About four hours after you should’ve gotten up.”

“That’s my brother, the King of Rights and Wrongs. Leave me alone, Aaron.”

“For chrissakes, Moe, you smell like a barroom floor. And when was the last time you shaved?”

“Gimme a drink. And how did you get in here, anyway?”

He jangled keys on a ring. “You gave me these when you were sick.”

“Give ’em back. And get me a fucking drink!”