The Honored Society: A Portrait of Italy's Most Powerful Mafia

Read The Honored Society: A Portrait of Italy's Most Powerful Mafia Online

Authors: Petra Reski

Tags: #True Crime, #Organized Crime, #History, #Europe, #Italy, #Social Science, #Violence in Society

THE

HONORED

SOCIETY

THE

HONORED

SOCIETY

A Portrait of Italy’s

Most Powerful Mafia

By Petra Reski

Translated by Shaun Whiteside

Preface to the American edition

translated by Ross Benjamin

First published in Germany in 2008 by Droemersche Verlagsanstalt Th. Knaur Nachf. GmbH & Co.

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © 2013 by Petra Reski Translation copyright © 2013 by Shaun Whiteside English translation of preface copyright © 2013 Ross Benjamin Published by Nation Books, A Member of the Perseus Books Group, 116

East 16th Street, 8th Floor, New York, NY 10003

Nation Books is a co-publishing venture of the Nation Institute and the Perseus Books Group.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address the Perseus Books Group, 250 West 57 Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Nation Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 255-1514, or e-mail

[email protected]

.

Designed by Linda Mark

Text set in 12 point Adobe Jenson Pro Light Library of Congress has catalogued the hardcover as follows: Reski, Petra.

[Mafia. English]

The honored society : the secret history of Italy’s most powerful Mafia / by Petra Reski ; translated by Shaun Whiteside ; introduction to the American edition translated by Ross Benjamin.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-56858-969-5 (e-book) 1. Mafia—Italy—History. I. Title.

HV6453.I83M3754 2013

364.1060945—dc23

2012039373

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Shobha

C

ONTENTS

S

ILVIO

B

ERLUSCONI AND

M

ARCELLO

D

ELL

’U

TRI

It was a balmy summer night when the German Mafia massacre occurred. On August 15, 2007, six Italians from Calabria were executed—in the middle of Duisburg, one of those cities built of brick in the Ruhr area, the old industrial heart of western Germany. The hit squad had fired over seventy shots. The youngest victim was sixteen years old, the oldest thirty-eight: Francesco and Marco Pergola, Sebastiano Strangio, Francesco Giorgi, Marco Marmo, and Francesco Tommaso Venturi. Five were killed instantly; the sixth died on the way to the hospital.

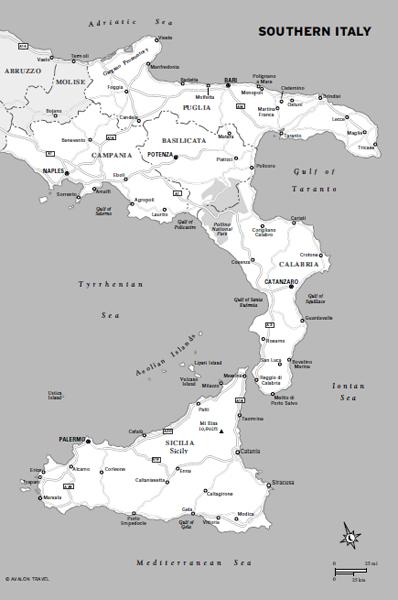

All the victims were from San Luca, the stronghold of the ’Ndrangheta, the Calabrian Mafia organization that was fourth on the White House list of the most dangerous criminal organizations in the world (“Narcotics Kingpin Organizations”), after al-Qaeda, the PKK, and the Mexican narcos. With its estimated annual turnover of 45 billion euros, the ’Ndrangheta is not only

the richest Mafia organization in Italy, but also the most mobile, the largest multinational Mafia organization—and the first to put down roots in Germany, where in the early 1960s, even before the Sicilian Cosa Nostra and the Campanian Camorra, it found its second home.

The hit men in Duisburg had surprised their victims in their cars in front of the Italian restaurant Da Bruno in the city center, not far from the train station. Here the Italians had in the hours before their deaths participated in what is for the Mafia a very special event: in the pocket of eighteen-year-old Francesco Tommaso Venturi was a burnt prayer card of the Archangel Gabriel. The six Italians had on that evening celebrated the induction of the youngest member into the clan.

The village of San Luca is known among Italian investigators as “the mother of crime,” as it is distinguished by a density—high even for Calabria—of thirty-nine clans to only four thousand residents. The Mafia families from San Luca count among the most powerful clans in the ’Ndrangheta—and in Germany possess enormous manpower adept in every type of crime. Whether in international narcotics or arms trafficking, shakedowns, abductions, car theft, or money laundering, the clans of San Luca look back on decades of experience. To avoid attracting attention in Germany, fresh young men who have no record of previous convictions but are related by blood to the bosses are regularly sent from San Luca.

On the morning after the night of the Duisburg murders, Germany was in shock. The Mafia always exists only once dead bodies are lying in the street. Germans knew the Mafia from the

Godfather

movies, perhaps from

The Sopranos

as well—but scarcely anyone had ever heard of the Italian Mafia organization

with the unpronounceable name ’

Ndrangheta

, which had brought its war to Germany. For decades two clans from San Luca, the Pelle-Vottari and the Nirta-Strangio, have been carrying on a feud for supremacy in drug and arms trafficking and for business in Germany.

Until the Duisburg bloodbath, the Mafia had always been regarded by Germans as only an Italian problem. The German constitutional state was well armed against all dangers, the argument had always gone; Germany was for the Mafia at most a “place of retreat,” as if the mafiosi used Germany as a vacation spot.

But as more and more investigations into Mafia activities in Germany came to light, the situation became increasingly unsettling. Suddenly Germans began to suspect that the Mafia had by no means descended on their country like a summer storm, but had already been well established in the heart of Germany for more than forty years. The situation was similar to the former state of affairs in America, where the Mafia was able to remain invisible for almost forty years and traffic in drugs until 1957, when the FBI raided a Mafia summit in Apalachin, New York, and arrested sixty-four bosses. Until then not many Americans had taken notice of the fact that as early as 1920 the second wave of Mafia immigration had already washed up on America’s shores.

It was exactly the same in Germany, where people were even more naive than in America. No one was bothered by the fact that the Mafia had been doing business there since the 1960s—in those places where southern Italian guest workers once found jobs on the assembly lines, in the steel mills, and in the mines. The classic bases of the Mafia in Germany are the industrial

centers in the west, south, and southwest: in North Rhine-Westphalia, Bavaria, Hesse, and Baden-Württemberg; in cities like Duisburg, Bochum, Oberhausen, Stuttgart, and Munich; and, since the fall of the Wall, in eastern Germany as well, particularly in cities like Erfurt and Leipzig.

The families of the Campanian Camorra and the Sicilian Cosa Nostra are also active in Germany. The Cosa Nostra brought many years of experience in the construction industry to Germany. Manipulating public contracts, carrying out building contracts as subcontractors without paying social welfare contributions or taxes—all that is a specialty of the Sicilians. Competition between the individual Italian Mafia organizations doesn’t exist. There are enough pieces of the German pie for everyone.

And it’s not only Germany. The clans of the ’Ndrangheta are the biggest fans of European freedom of travel. They’re also active in Holland and Belgium, where they control the ports; in France they’ve invested in villas on the Côte d’Azur; in the Balkans they control the drug-smuggling routes; and in Bulgaria they invest in tourism. They do all this in harmony with the clans of the Sicilian Cosa Nostra and the Neapolitan Camorra, who have learned from the mobility of the ’Ndrangheta and have long done business throughout Europe as well. Not only does a considerable stretch of the Spanish Costa del Sol belong to the Neapolitan Camorra; it’s also active in England and Scotland, where its members invest in real estate and give themselves cover with import-export enterprises. The European economic crisis promotes the business of the Mafia tremendously. When there’s no money, people don’t look as closely at where it comes from.

Because the Duisburg Mafia massacre first gave the lie to the myth of Germany as a “place of retreat” for mafiosi, the bloody night in Duisburg was a mishap, at least from the Mafia’s perspective. For it was certainly not in the clans’ interest to make unequivocally clear that the Mafia was not an exclusively Italian problem, but a global one. No sooner had the Duisburg corpses been buried than the Italian secret service from Calabrian San Luca reported that the two enemy clans, the Pelle-Vottari and the Nirta-Strangio, had declared a truce. That was also entirely in the interest of German politics—which had no more desire than the bosses to discuss the topic of the “Mafia in Germany.” There was reluctance not only to alarm the citizenry, but also to endanger the investments of the ’Ndrangheta. Whole eastern German city centers were rebuilt with ’Ndrangheta money after the fall of the Wall.