The House of Twenty Thousand Books (34 page)

Read The House of Twenty Thousand Books Online

Authors: Sasha Abramsky

***

As I neared completion of this manuscript, more than three years after my grandfather’s death, I had another dream. This time, Chimen’s books had been restored to their shelves, not quite in the right order, but in something approximating his library’s structure. The books were stacked in strange formations, lying horizontally, many of the spines, with the titles on them, turned inwards, away

from

the casual viewer. And Chimen had been resurrected.

One after the other, the books righted themselves. And, as they did so, Chimen got increasingly animated. His back straightened, his hearing improved. And, with a slight, crooked smile, he began arguing again, talking about his books, debating his grand ideas. Outside his house was chaos. I saw, in my dream, huge encampments of the homeless, overcrowded trains, great, noisy restaurants. Inside Hillway, however, was a strange, musty order.

I woke up. It was 5 a.m. I was wide-awake; as awake, as alert, as a young child after twelve hours of sleep. As the dream began to fade, I did what Chimen would have done. I reached for a piece of paper and I scribbled down the images. I filed the piece of paper in one of the boxes full of notes for my book. One doesn’t throw away words. They might, someday, be useful.

T

HROUGHOUT MY DECADES

as a writer, I have always known that one day I would write a book about my grandparents and their remarkable house. I didn’t know what shape the book would take, nor how I would frame their lives; but I knew that theirs was a story that I had to tell.

After my grandfather died in March 2010, telling that story became one of the driving forces of my life. It became rather more than an itch, something much closer to an obsession. Chimen and Mimi’s world, centred around the book- and conversation-filled rooms of 5 Hillway, was one that, by the day, was dying: the central characters in their lives were either very old or already dead; the political battles they fought were, increasingly, seen as footnotes from the distant past; the books and ideas they valued were getting dustier by the day. If I were to tell their story, I had to do it sooner rather than later.

And so I set to work. I wanted to write

The House of Twenty Thousand Books

using the story-telling, descriptive techniques that

I have developed over twenty years as a journalist; but I also wanted to tell it as a history, to use archives and libraries in a way that Chimen, a consummate historian, would have approved. I eventually decided upon a compromise: I would do deep research, in archives, and via interviews, but I wouldn’t footnote my text. I would tell a story and trust my readers to trust me. I hope I have, in the telling, earned that trust.

The journey I embarked on took me nearly four years. Along the way, I read hundreds of books – many volumes from my grandfather’s collection and also histories, biographies, and novels that brought alive to me the worlds Chimen and Mimi inhabited. I interviewed scores of people (in person, by phone, by email) in England, the United States, Israel, Canada, Germany, Holland, Lithuania and elsewhere, and spent weeks in archives in London, Oxford, Sheffield and Manchester. It was a life-changing experience, opening my eyes to things I did not previously know or understand; introducing me to my great-grandparents and grandparents as children, as young adults, as middle-aged and elderly men and women, as well as to fascinating historical characters now long dead; and allowing me to see my grandparents’ lives – and by extension my own – as part of a religious, cultural, political and migratory history going far back into the mists of time.

None of this would have been possible without the extraordinary support of a vast number of people. First and foremost, I owe an immeasurable debt of gratitude to my parents, Jack and Lenore Abramsky – for participating, with me, in the joy of this project, and for having confidence in my ability to tie the loose strands together. My father, in particular, took to this project with the zest and enthusiasm of a young man, helping me with archival research, finding documents buried deep in family filing cabinets, filling in gaps in my knowledge of key people and key events, and, most importantly, trusting me to tell his parents’ story

with respect. On several occasions we visited key locales together, such as the street that had once played home to the Shapiro, Valentine & Co book shop; I shall always treasure those memories. Both my parents tolerated, with good humour, my endless requests for additional information. It cannot be easy having a son snooping around one’s inner life; that neither my mother nor my father protested is a gift for which I will be eternally thankful. So, too, my aunt Jenny was generous to a fault, in opening up her house to me while I burrowed in her files, in talking to me about her childhood memories, and in providing me access to the thousands of letters written by, or to, my grandparents. My brother, Kolya, knew the socialist side of Chimen’s collection better than any other member of the family. His extraordinary knowledge and insights, his generosity in suggesting sources for me to read, and his insistence in gently but firmly critiquing some of my interpretations of events were of absolutely critical importance to me as I brought this book to fruition. We didn’t always agree in our understanding of chapters in Mimi and Chimen’s lives, but I never doubted for a moment his wisdom. My sister Tanya, my cousins Rob and Maia, Emma and Nick all opened up their memory chests to me time and again over the years that I was writing this, providing a wealth of anecdotes that I had long forgotten or, in some cases, never previously known. So, too, did generations of other relatives: Eve and Julia Corrin; Alison Light; Lily and Martin Mitchell; Peter and Vavi Hillel; Elliott Medrich; Alice Medrich; Mildred Axelrod; Larry and Shirley Kedes and many others. Late in the writing process, my cousin Ron Abramski provided me with a copy of an extraordinary filmed interview that he had conducted with Chimen in January 2003.

The number of friends and colleagues of my grandparents, and of my parents, who helped me by agreeing both to be interviewed for this project and also to photocopy or scan letters

and other documents are legion: I cannot possibly list everybody by name, but you know who you are. I do, however, owe, special thanks: to Chimen’s University College colleague Ada Rapoport-Albert; to his friends at Stanford – Peter and Suzanne Greenberg (whose wonderful hospitality and keen interest both in people and in ideas has always reminded me of that exuded by Mimi and Chimen) and Peter Stansky; to Helen Beer, in Oxford, and to Marion Aptroot and Efrat Gal-Ed, in Germany – all of whom helped me understand, and in some cases translate, Chimen’s wonderful collection of Yiddish literature; to Miri Freud-Kandel, in Oxford and to Rabbi Elliot Cosgrove, in New York, both of whom went out of their way to explain my great-grandfather’s role in English Jewish religious life over the decades; to Pauline Harrison, whose insights into the psychology of the Communist Party of Great Britain in the years surrounding the Second World War fascinated me; to Lord John Kerr, who championed Chimen at Sotheby’s and, later, at Bloomsbury Auctions; to Ormond Uren, one of the last of the lions; and to Chimen’s great book-collecting friend, and global travel companion in his later years, Jack Lunzer.

Krishan Kumar, Andrew Moss, Tariq Ali, Christo Hird, Jon and Michael Pushkin, Peter Waterman, Gidon Cohen, Kevin Morgan, Eilat Negev and Yehuda Koren, Tony Yablon, David Mazower, Arie Dubnov, Dovid Katz, John Felstiner, Berel Rodal and Graham Thorpe all provided reminiscences of life at Hillway and of personal and professional interactions with Miriam and Chimen over more than half a century. Beryl Williams arranged for the digitising of Chimen’s 1967 Sussex University lectures, given to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Russian Revolution. Christopher Edwards was instrumental in helping familiarise me with the often-opaque world of rare book dealing. Camilla Prévité and Nabil Saidi were similarly generous in helping me to understand the auction house world of Sotheby’s.

In addition to these friends and colleagues, I was immensely

fortunate to have several extremely talented teams of archivists eager to work with me on this project: to the men and women who staff the libraries and archives at University College London; the Bishopsgate Institute, also in London; the People’s History Museum, in Manchester; the special collections room at the University of Sheffield; Stanford University, in California; the Bodleian Library, Kressel Archive, and St. Antony’s College, in Oxford; and Trinity College, Cambridge, I send a huge thank you, which I hope will echo loudly and proudly through the silent chambers and reading rooms of your great institutions. An equally loud thank you, too, to Philippa Bernard, at Westminster Synagogue; and, of course, to Henry Hardy of the Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust and Mark Pottle, who have edited Berlin’s letters so skillfully over the years.

Beyond these circles, I repeatedly sought – and received – assistance from a magnificent brains’ trust: my friends Nathaniel Deutsch, and his wife Miriam Greenberg, went far, far beyond the call of duty in researching answers to my questions, and in correcting my sometimes flawed understandings of Jewish history and religious ritual. Without Nathaniel’s enthusiastic assistance, and his translation of key documents from Hebrew into English, as well as his and Miriam’s willingness to host me in their home in Santa Cruz while we discussed the project’s evolution, I doubt very much that I could have brought this book to completion. So too, Steve Zipperstein, at Stanford, allowed me to pick his brains over a series of wonderful brunches in Palo Alto. I very much hope that he will continue to indulge me in these conversations after the publication of this book. At the University of California at Davis, David Biale never failed to generously respond to my requests for information and for book references. In Berkeley, Paul Hamburg, the librarian presiding over the university’s Hebraica collection, both helped me to understand the importance of some of Chimen’s oldest and rarest Hebrew books

and manuscripts and also showed me equivalent books owned by the university. At George Washington University, Brad Hill, who many years ago apprenticed himself to my grandfather while he was learning the mysterious arts of Hebrew bibliography, conjured up a simply extraordinary amount of information and personal correspondence; Hill went so far as to draw up for me a complete bibliography of my grandfather’s writings. I shall be forever grateful for this act.

Many of my oldest, and dearest, friends also made themselves available over the years to talk over sections of the book, to provide specific historical details, or simply to help me maintain my enthusiasm during what was sometimes an emotionally draining project. Particular thanks here go to Pete Sarris, Ben Caplin, Eyal Press, Adam Shatz, Baki Tezcan (whose knowledge of Turkish history gave me an entry point into the world of Constantinople’s Hebrew printers five hundred years ago), George Lerner, Jason Ziedenberg, Jon Wedderburn, Kitty Ussher and Carolyn Juris. My mentors at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, Michael Shapiro and Sam Freedman, were also instrumental in convincing me that I had the wherewithal to tell this story.

In London, my editors Peter and Martine Halban embraced the concept of

The House of Twenty Thousand Books

from our very first conversation; and, as the book moved towards publication, Kim Reynolds’s historical expertise and first-rate editing skills were indispensable in knocking the rough edges off of my manuscript. My agents, Victoria Skurnick in New York and Caspian Dennis in London, also deserve my warmest thanks.

Last but of course not least, to my wife Julie Sze, to my daughter Sofia, and to my son Leo, my profoundest thank you for tolerating my workaholic tendencies during the gestation of

The House of Twenty Thousand Books

; for your belief in the importance of this story; and for your joyful interest in the sagas

contained in these pages. Thank you, too, for always helping me to keep things in perspective. You make my home warm and my life full.

During the years that it took me to write this book, many wonderful friends and relatives died. Amongst them were my uncle Al Liddell; my great aunt Sara Corrin; Chimen’s Oxford friend Harry Shukman; and his erstwhile Communist Party comrade Eric Hobsbawm. Every day, it seems, our past becomes more unrecoverable, the living links to that past more fragile. My book is, in many ways, a chorus of ghosts.

I hope that, in its own small way,

The House of Twenty Thousand Books

helps memorialise the men and women who, collectively, made up the world of 5 Hillway. They are, in the main, no longer alive, but their voices still resonate, for me, with the clear, loud, tones of Bow Bells. They were, one and all, remarkable human beings.

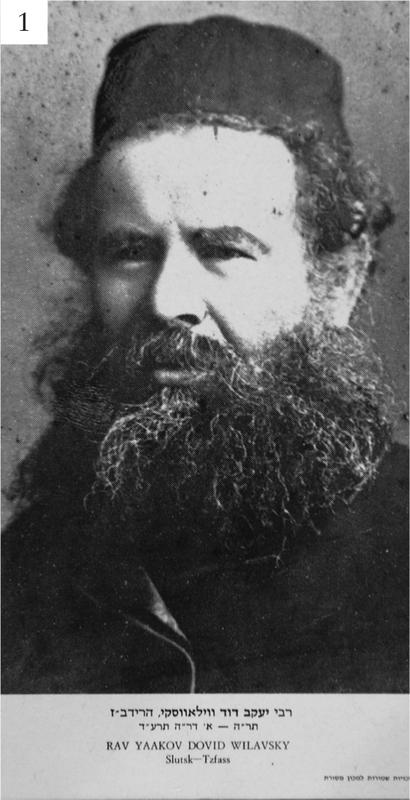

1. Rabbi Yaakov Dovid Willowski, called ‘The Ridbaz’. He was Chimen’s great-grandfather. He visited the United States but returned to the Lithuanian yeshivas in disgust. Date unknown.

2. The Nirenstein family.

L to r:

Sara, Bellafeigel, Minna, Jacob and Miriam. London,

circa

1922.

3. Yehezkel and Raizl with their daughters-in-law and grandchildren.

Back row, l to r:,

Chaya Sara, Mimi, Jack.

Front row, l to r:

Raizl, Jenny, Mordechai Samuel, Yehezkel, Zipporah and Samson. London, mid-1950s.

4. Jacob Nirenstein in front of the shop which became Shapiro, Valentine & Co., in Wentworth Street, London. Date unknown.

5.

L to r:

Chimen, Moshe, Jack, Raizl, Menachem and Yehezkel. London, 1951.

Yehezkel and Raizl were at the railway station on their way to the boat that would take them to their retirement in Israel.

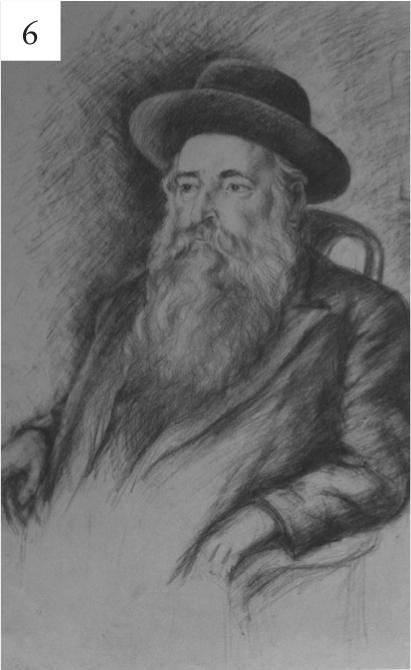

6. Yehezkel Abramsky, sketched by Hendel Lieberman. London, 1950. It hung in the front room at Hillway.

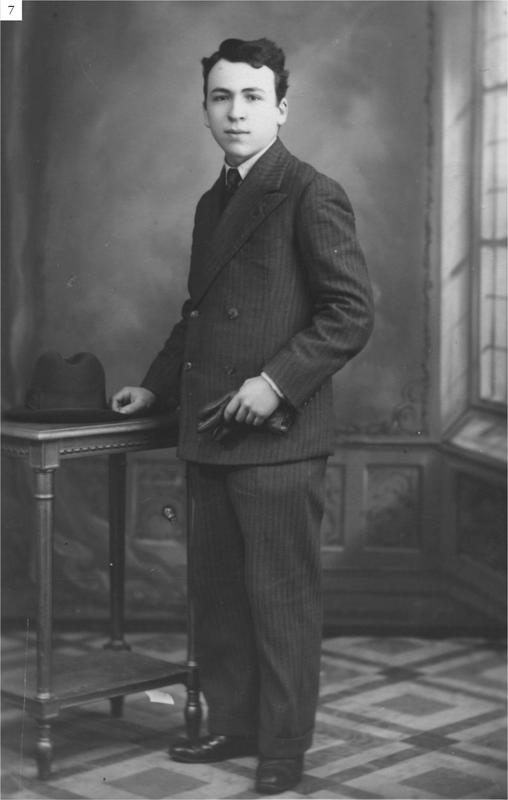

7. Chimen as a student in Jerusalem, late 1930s.

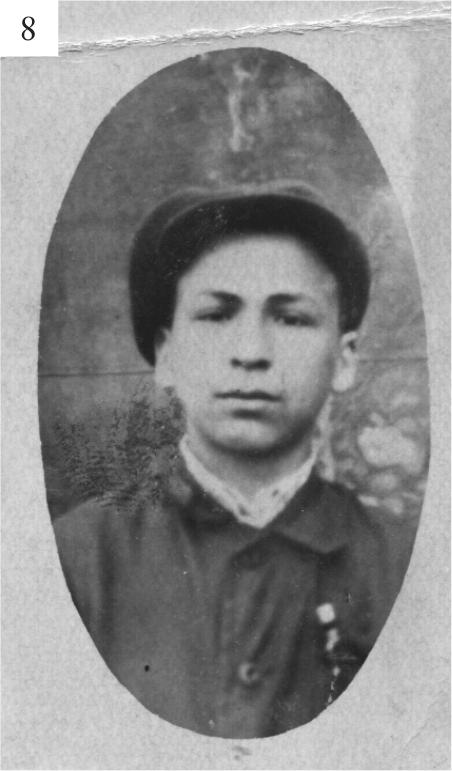

8. Chimen as a teenager in Moscow,

circa

1929.

9. Chimen and Mimi at the time of their marriage. London, June 1940.

10. One of the marches for jobs organised by the Communist Party, London, mid-1930s. Mimi is at the front, holding the rope for the banner.

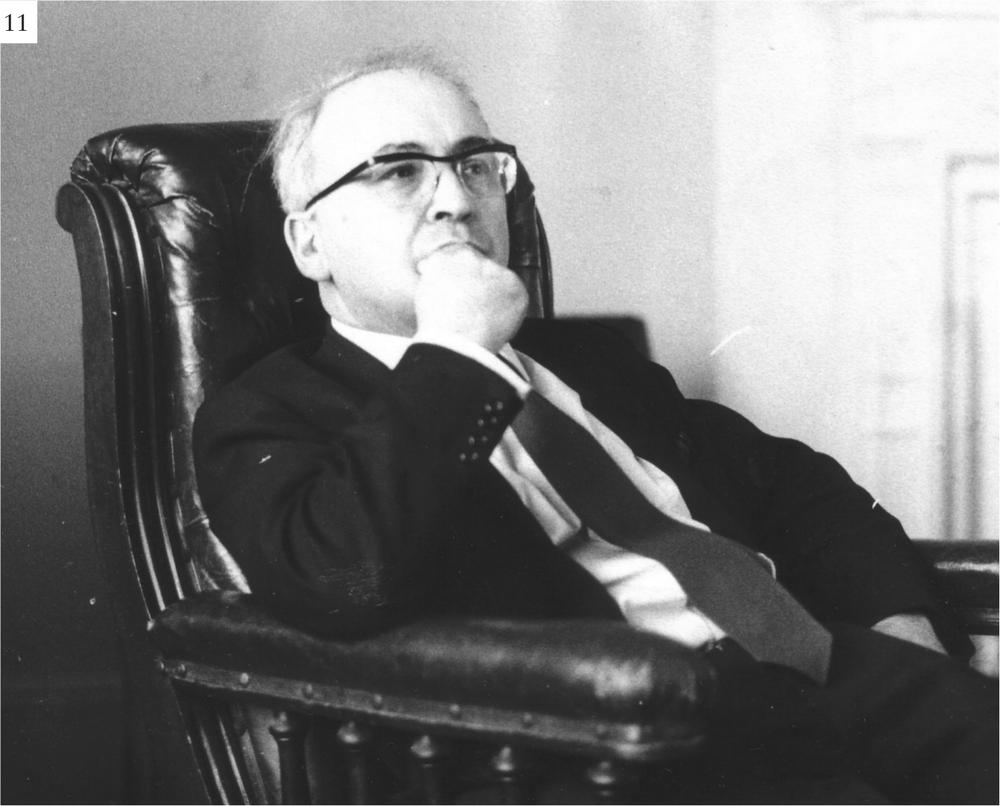

11. Chimen in his office at St. Antony’s College, Oxford, mid-1960s.

12. Chimen on holiday at the beach in Dorset.

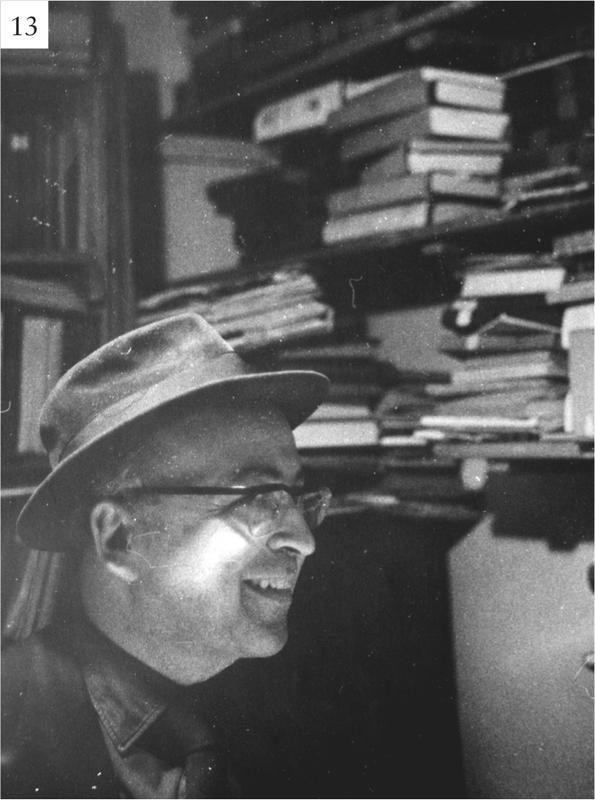

13. Chimen at his book shop, Shapiro, Valentine & Co. Early 1960s.