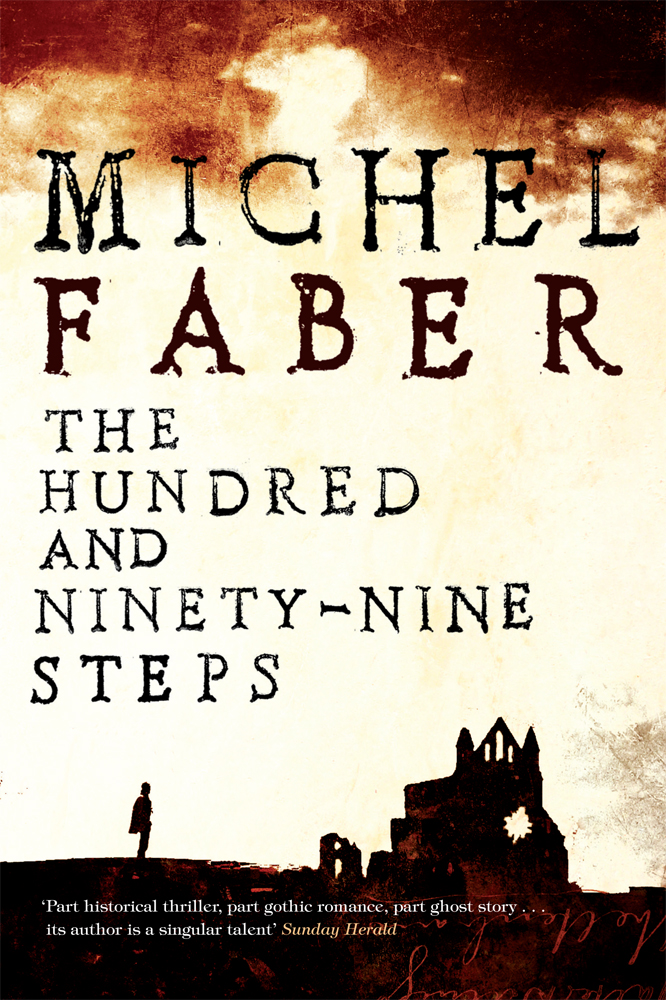

The Hundred and Ninety-Nine Steps

So word by word, and line by line,

The dead man touch'd me from the past

â¦

Tennyson, âIn Memoriam'

THE HAND CARESSING HER CHEEK

was gentle but disquietingly large â as big as her whole head, it seemed. She sensed that if she dared open her lips to cry out, the hand would cease stroking her face and clasp its massive fingers over her mouth.

âJust let it happen,' his voice murmured, hot, in her ear. âIt's going to happen anyway. There's no point resisting.'

She'd heard those words before, should have known what was in store for her, but somehow her memory had been erased since the last time he'd held her in his arms. She closed her eyes, longing to trust him, longing to rest her head in the pillowy crook of his arm, but at the last instant, she glimpsed sideways, and saw the knife in his other hand. Her scream was gagged by the blade slicing deep into her throat, severing everything right through to the bone of her spine, plunging her terrified soul into pitch darkness.

Bolt upright in bed, Siân clutched her head in her hands, expecting it to be lolling loose from her neck, a grisly hallowe'en pumpkin of bloody flesh. The shrill sound of screaming whirled around her room. She was alone, as always, in the early dawn of a Yorkshire summer, clutching her sweaty but otherwise unharmed head in the topmost bedroom of the White Horse and Griffin Hotel. Outside the attic window, the belligerent chorus of Whitby's seagull hordes shrieked on and on. To other residents of the hotel (judging by their rueful comments at the breakfast tables), these birds sounded like car alarms or circular saws or electric drills penetrating hardwood. Only to Siân, evidently, did they sound like her own death cries as she was being decapitated.

It was true that ever since the accident in Bosnia, Siân's dreams had treated her pretty roughly. For years on end she'd had her âstandard-issue' nightmare â the one in which she was chased through dark alleyways by a malevolent car. But at least in

that

dream she'd always wake up just before she fell beneath the wheels, whisked to the safety of the waking world, still flailing under the tangled sheets and blankets of her bed. Ever since she'd moved to Whitby, however, her dreams had lost what little good taste they'd once had, and now Siân was lucky if she got out of them alive.

The White Horse and Griffin had a plaque out front proudly declaring it had won

The Sunday Times

Golden Pillow Award, but Siân's pillow must be immune to the hotel's historically sedative charm. Tucked snugly under the ancient sloping roof of the Mary Ann Hepworth room, with a velux window bringing her fresh air direct from the sea, Siân still managed to toss sleepless for hours before finally being lured into nightmare by the man with the giant hands. She rarely woke without having felt the cold steel of his blade carving her head off.

This dream of being first seduced, then murdered â always by a knife through the neck â had ensconced itself so promptly after her arrival in Whitby that Siân had asked the hotel proprietor if ⦠if he happened to know how Mary Ann Hepworth had met her death. Already embarrassed that a science postgraduate like herself should stoop to such superstitious probings, she'd blushed crimson when he informed her that the room was named after a ship.

In the cold light of a Friday morning, swallowing hard through a throat she couldn't quite believe was still in one piece, Siân squinted at her watch. Ten to six. Two-and-a-bit hours to fill before she could start work. Two-and-a-bit hours before she could climb the one hundred and ninety-nine steps to the abbey churchyard and join the others at the dig.

A bath would pass the time, and would soak these faint mud-stains off her forearms, these barely perceptible discolorations ringing her flesh like alluvial deposits. But she was tired and irritable and there was a pain in her left hip â a nagging, bone-deep pain that had been getting worse and worse lately â and she was in no mood to drag herself into the tub. What a lousy monk or nun she would have made, if she'd lived in medieval times. So reluctant to subject her body to harsh discipline, so lazy about leaving the warmth of her bed â¦! So frightened of death.

This pain in her hip, and the hard lump that was manifesting in the flesh of her thigh just near where the pain was â it had to be bad news, very bad news. She should get it investigated. She wouldn't, though. She would ignore it, bear it, distract herself from it by concentrating on her work, and then one day, hopefully quite suddenly, it would be all over.

Thirty-four. She was, as of a few weeks ago, over half the age that good old Saint Hilda reached when she died. Seventh-century medical science wasn't quite up to diagnosing the cause, but Siân suspected it was cancer that had brought an end to Hilda's illustrious career as Whitby's founding abbess. Her photographic memory retrieved the words of Bede: âIt pleased the Author of our salvation to try her holy soul by a long sickness, in order that her strength might be made perfect in weakness.'

Made perfect in weakness! Was there a touch of bitter sarcasm in the Venerable Bede's account? No, almost certainly not. The humility, the serene stoicism of the medieval monastic mind â how terrifying it was, and yet how wonderful. If only she could think like that, feel like that, for just a few minutes! All her fears, her miseries, her regrets, would be flushed out of her by the pure water of faith; she would see herself as a spirit distinct from her treacherous body, a bright feather on the breath of God.

All very well, but I'm still not having a bath

, she thought grouchily.

Through the velux window she could see a trio of seagulls, hopping from roof-tile to roof-tile, chortling at her goose-pimpled, wingless body as she threw aside the bedclothes. She dressed hurriedly, got herself ready for the day. The best thing about hands-on archaeology like the Whitby dig was that no-one expected anybody to look glamorous, and you could wear the same old clothes day in, day out. She'd have to smarten herself up when she returned to her teaching rounds in the autumn; there was nothing like a lecture hall full of students, some of them young males, scrutinising you as if to say, âWhere did they dig

her

up?' to focus your mind on what skirt and top you ought to wear.

Before descending the stairs to the breakfast room, Siân took a swig from the peculiar little complimentary bottle of mineral water and looked out over the roof-tops of Whitby's east side. The rising sun glowed yellow and orange on the terracotta ridges. Obscured by the buildings and a litter of sails and boat-masts, the water of the river Esk twinkled indigo. Deep in Siân's abdomen, a twinge of pain made her wince. Was it indigestion, or something to do with the lump in her hip? She mustn't think about it. Go away, Venerable Bede! âIn the seventh year of her illness,' he wrote of Saint Hilda, âthe pain passed into her innermost parts.' Whereupon, of course, she died.

Siân went downstairs to the breakfast room, hoping that if she could find something to eat, the pain in her innermost parts might settle down. It was much too early, though, and the room was dim and deserted, with tea-towels shrouding the cereal boxes and the milk jug empty. Siân considered eating a banana, but it was the last one in the bowl and she felt, absurdly, that this would make the act sinful somehow. Instead she ate a couple of grapes and wandered around the room, touching each identically laid, melancholy table with her fingertips. She seated herself at one, thinking of the Benedictine monks and nuns in their refectories, forbidden to speak except for the reciting of Holy Scripture. Dreamily pretending she was one of them, she lifted her hands into the pale light and gestured in the air the mute signals for fish, for bread, for wine.

âAre you all right?'

Siân jerked, almost knocking a teacup off the table.

âYes, yes,' she assured the Horse and Griffin's kitchen-maid, large as life in the doorway. âFine, thank you.' She sighed. âJust going batty.'

âI don't wonder,' said the kitchen-maid. âAll them bodies.'

âBodies?'

âThe skeletons you've been diggin' up.' The girl made a face. âSixty of 'em, I read in the

Whitby Gazette

.'

âSixty graves. We haven't actuallyâ'

âD'you 'ave to touch 'em? I'd be sickened off. You wear gloves, I 'ope.'

Siân smiled, shook her head. The girl's look of horrified awe beamed at her across the breakfast room like a ray, and she basked shyly in it: Siân the daredevil. For the sake of the truth, she ought to disabuse this girl of her fantasy of archaeologists rooting elbow-deep in grisly human remains, and tell her that the dig was really very like gardening except less eventful. But instead, she raised her hands and wiggled the fingers, as if to say,

Ordinary mortals cannot know what I have touched

.

âBraver than me, you are,' said the girl, unveiling the milk.

To help time pass, Siân crossed the bridge from the less corrupted east side to the more newfangled west, and strolled along Pier Road towards the sea. Thinly gilded with sunlight, the façades of the amusement arcades and clairvoyants' cabins looked almost grand, their windows and shuttered doors deflecting the glare. Siân dawdled in Marine Parade to peer through the window of what, until 1813, had been the Whitby Commercial Newsroom. âThe Award-Winning Dracula Experience' said the poster, followed by a list of attractions, including voluptuous female vampires and Christopher Lee's cape.

The fish quay, deserted just now, was nevertheless infested with loitering seagulls. They wandered around aimlessly in the sunrise, much as the town's young men would do after sunset, or simply snoozed on top of crates and the roofs of the moored boats.

Siân walked to the lighthouse, then left the terra firma of Aislaby sandstone to tread the timber deck of the pier's end. Careful not to snag the heels of her shoes on the gaps in the wood, she allowed herself the queasy thrill of peeking at the restless waves churning far beneath her feet. She wasn't sure if she could swim anymore; it had been a long time.

She stood at the very end of the west pier and cupped her hand across her brow to look over at the east one. The two piers were like outstretched arms curving into the ocean, to gather boats from the wild waters of the North Sea into the safety of Whitby harbour. Siân was standing on a giant fingertip.

She consulted her watch and walked back to the mainland. Her work was on the other side.

Ascending the East Cliff, half-way up the one hundred and ninety-nine stone steps, Siân paused for a breather. Much as she loved to walk, she'd overdone it, perhaps, so early in the day. She should keep in mind that instead of going to sit at a desk now, she was going to spend the whole day digging in the earth.

Siân traced the imperfections of the stone step with her shoe, demarcating the erosion caused by the foot traffic of centuries. On just this spot, this wide plateau-like step amongst many narrow ones, the townspeople of ancient Whitby laid down the coffins they must carry up to the churchyard, and had paused, black-clad and red-faced, before resuming their doleful ascent. Only now that tourists and archaeologists had finally taken the place of mourners did these steps no longer accommodate dead people â apart from the occasional obese American holiday-maker who collapsed with a heart attack before reaching the hallowed photo-opportunity.

Siân peered down towards Church Street and saw a man jogging â no, not jogging, running â towards the steps. At his side, a dog â a gorgeous animal, the size of a spaniel perhaps, but with a lovely thick coat, like a wolf's. The man wasn't bad-looking himself, broad-shouldered and well-muscled, pounding the cobbled surface of the street with his expensive-looking trainers. He was dressed in shorts and a loose, thin sweatshirt, a shivery proposition in the early morning chill, but he was obviously well up to it. His face was calm as he ran, his dark brown hair, free of sweat, flopping back and forth across his brow. The dog looked up at him frequently as he ran, revealing the vanilla and caramel colouring in its mane.