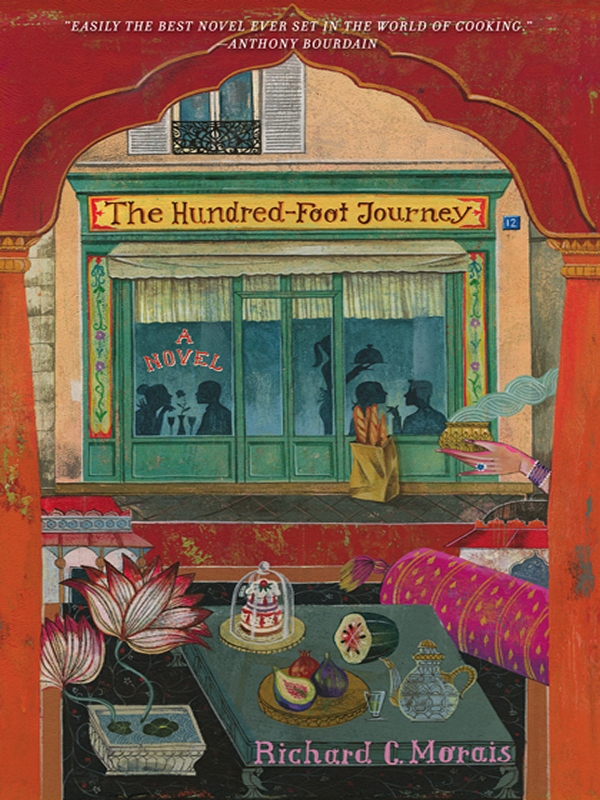

The Hundred-Foot Journey

Read The Hundred-Foot Journey Online

Authors: Richard C. Morais

Tags: #Food, #Contemporary Fiction, #Cooking

A Novel

Richard C. Morais

SCRIBNER

SCRIBNER

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2008, 2010 by Richard C. Morais

An earlier edition of this work was originally published in India in 2008 by HarperCollins Publishers India

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Scribner hardcover edition July 2010

SCRIBNER

and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or [email protected].

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at

www.simonspeakers.com

.

DESIGNED BY ERICH HOBBING

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Morais, Richard C., 1960–

The hundred-foot journey : a novel / by Richard C. Morais.

—1st Scribner hardcover ed.

p. cm.

1. Cooks—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3613.O584H86 2010

813'.6—dc22 2009050619

ISBN 978-1-4391-6564-5

ISBN 978-1-4391-6566-9 (ebook)

For Katy and Susan

Mumbai

Chapter One

I, Hassan Haji, was born, the second of six children, above my grandfather’s restaurant on the Napean Sea Road in what was then called West Bombay, two decades before the great city was renamed Mumbai. I suspect my destiny was written from the very start, for my first sensation of life was the smell of machli ka salan, a spicy fish curry, rising through the floorboards to the cot in my parents’ room above the restaurant. To this day I can recall the sensation of those cot bars pressed up coldly against my toddler’s face, my nose poked out as far as possible and searching the air for that aromatic packet of cardamom, fish heads, and palm oil, which, even at that young age, somehow suggested there were unfathomable riches to be discovered and savored in the free world beyond.

But let me start at the beginning. In 1934, my grandfather arrived in Bombay from Gujarat, a young man riding to the great city on the roof of a steam engine. These days in India many up-and-coming families have miraculously discovered noble backgrounds—famous relatives who worked with Mahatma Gandhi in the early days in South Africa—but I have no such genteel heritage. We were poor Muslims, subsistence farmers from dusty Bhavnagar, and a severe blight among the cotton fields in the 1930s left my starving seventeen-year-old grandfather no choice but to migrate to Bombay, that bustling metropolis where little people have long gone to make their mark.

My life in the kitchen, in short, starts way back with my grandfather’s great hunger. And that three-day ride atop the train, baking in the fierce sun, clinging for dear life as the hot iron chugged across the plains of India, was the unpromising start of my family’s journey. Grandfather never liked to talk about those early days in Bombay, but I know from Ammi, my grandmother, that he slept rough in the streets for many years, earning his living delivering tiffin boxes to the Indian clerks running the back rooms of the British Empire.

To understand the Bombay from where I come, you must go to Victoria Terminus at rush hour. It is the very essence of Indian life. Coaches are split between men and women, and commuters literally hang from the windows and doors as the trains ratchet down the rails into the Victoria and Churchgate stations. The trains are so crowded there isn’t even room for the commuters’ lunch boxes, which arrive in separate trains after rush hour. These tiffin boxes—over two million battered tin cans with a lid—smelling of daal and gingery cabbage and black pepper rice and sent on by loyal wives—are sorted, stacked into trundle carts, and delivered with utmost precision to each insurance clerk and bank teller throughout Bombay.

That was what my grandfather did. He delivered lunch boxes.

A

dabba-wallah

. Nothing more. Nothing less.

Grandfather was quite a dour fellow. We called him Bapaji, and I remember him squatting on his haunches in the street near sunset during Ramadan, his face white with hunger and rage as he puffed on a beedi. I can still see the thin nose and iron-wire eyebrows, the soiled skullcap and kurta, his white scraggly beard.

Dour he was, but a good provider, too. By the age of twenty-three he was delivering nearly a thousand tiffin boxes a day. Fourteen runners worked for him, their pumping legs wrapped in lungi—the poor Indian man’s skirt—trundling the carts through the congested streets of Bombay as they off-loaded tinned lunches at the Scottish Amicable and Eagle Star buildings.

It was 1938, I believe, when he finally summoned Ammi. The two had been married since they were fourteen and she arrived with her cheap bangles on the train from Gujarat, a tiny peasant with oiled black skin. The train station filled with steam, the urchins made toilet on the tracks, and the water boys cried out, a current of tired passengers and porters flowing down the platform. In the back, third-class with her bundles, my Ammi.

Grandfather barked something at her and they were off, the loyal village wife trailing several respectful steps behind her Bombay man.

It was on the eve of World War II that my grandparents set up a clapboard house in the slums off the Napean Sea Road. Bombay was the back room of the Allies’ Asian war effort, and soon a million soldiers from around the world were passing through its gates. For many soldiers it was their last moments of peace before the torrid fighting of Burma and the Philippines, and the young men cavorted about Bombay’s coastal roads, cigarettes hanging from their lips, ogling the prostitutes working Chowpatty Beach.

It was my grandmother’s idea to sell them snacks, and my grandfather eventually agreed, adding to the tiffin business a string of food stalls on bicycles, mobile snack bars that rushed from the bathing soldiers at Juhu Beach to the Friday evening rush-hour crush outside the Churchgate train station. They sold sweets made of nuts and honey, milky tea, but mostly they sold bhelpuri, a newspaper cone of puffed rice, chutney, potatoes, onions, tomatoes, mint, and coriander, all mixed together and slathered with spices.

Delicious, I tell you, and not surprisingly the snack-bicycles became a commercial success. And so, encouraged by their good fortune, my grandparents cleared an abandoned lot on the far side of the Napean Sea Road. It was there that they erected a primitive roadside restaurant. They built a kitchen of three tandoori ovens—and a bank of charcoal fires on which rested iron kadais of mutton masala—all under a U.S. Army tent. In the shade of the banyan tree, they also set up some rough tables and slung hammocks. Grandmother employed Bappu, a cook from a village in Kerala, and to her northern repertoire she now added dishes like onion theal and spicy grilled prawns.

Soldiers and sailors and airmen washed their hands with English soap in an oil drum, dried themselves on the proffered towel, and then clambered up on the hammocks strung under the shady tree. By then some relatives from Gujarat had joined my grandparents, and these young men were our waiters. They slapped wooden boards, makeshift tables, across the hammocks and quickly covered them with bowls of skewered chicken and basmati and sweets made from butter and honey.

During slow moments Grandmother wandered out in the long shirt and trousers we call a

salwar kameez,

threading her way between the sagging hammocks and chatting with the homesick soldiers missing the dishes of their own countries. “What you like to eat?” she’d ask. “What you eat at home?”

And the British soldiers told her about steak-and-kidney pies, of the steam that arose when the knife first plunged into the crust and revealed the pie’s lumpy viscera. Each soldier tried to outdo the other, and soon the tent filled with oohing and “cors” and excited palaver. And the Americans, not wishing to be outdone by the British, joined in, earnestly searching for the words that could describe a grilled steak coming from cattle fed on Florida swamp grass.

And so, armed with this intelligence she picked up in her walkabouts, Ammi retreated to the kitchen, re-creating in her tandoori oven interpretations of what she had heard. There was, for example, a kind of Indian bread-and-butter pudding, dusted with fresh nutmeg, that became a hit with the British soldiers; the Americans, she found, they were partial to peanut sauce and mango chutney folded in between a piece of naan. And so it wasn’t long before news of our kitchen spread from Gurkha to British soldier, from barracks to warship, and all day long jeeps stopped outside our Napean Sea Road tent.

Ammi was quite remarkable and I cannot give her enough credit for what became of me. There is no dish finer than her pearlspot, a fish she dusted in a sweet-chili masala, wrapped in a banana leaf, and tawa-grilled with a spot of coconut oil. It is for me, well, the very height of Indian culture and civilization, both robust and refined, and everything that I have ever cooked since is held up against this benchmark, my grandmother’s favorite dish. And she had that amazing capacity of the professional chef to perform several tasks at once. I grew up watching her tiny figure darting barefoot across the earthen kitchen floor, quickly dipping eggplant slices in chickpea flour and frying them in the kadai, cuffing a cook, passing me an almond wafer, screeching her disapproval at my aunt.