The Hundred Years War (4 page)

Read The Hundred Years War Online

Authors: Desmond Seward

Slowly France and England lumbered into war. On 24 May 1337 King Philip declared that Guyenne had been forfeited by Edward ‘because of the many excesses, rebellious and disobedient acts committed by the King of England against Us and Our Royal Majesty’, citing in particular Edward’s harbouring of the sorcerer Robert of Artois. This declaration is generally considered to be the beginning of the Hundred Years War. In October Edward responded with a formal letter of defiance to ‘Philip of Valois who calls himself King of France’, laying claim to the French throne.

Philip VI immediately began a formidable onslaught on Guyenne, which lasted for three years. In 1339 his troops took Blaye on the north bank of the Gironde estuary, threatening Bordeaux’s access to the sea, and in 1340 took Bourg at the mouth of the Dordogne. On the Garonne, La Réole was again captured by the French who then besieged Saint-Macaire nearer the ducal capital. Besides disrupting the main lines of transport and communication, they laid waste the rich vineyard country of Entre-Deux-Mers and Saint-Emilion and made a determined attempt to take Bordeaux itself. Guyenne only survived because after 1340 Philip was busy elsewhere.

Meanwhile, Edward encircled France with a string of alliances. In August 1337, with a massive bribe, he landed no less a catch than the Holy (though excommunicated) Roman Emperor Ludwig IV, who was Philippa’s brother-in-law. After establishing himself and his Queen at a splendid headquarters in Antwerp, Edward went with much pomp to meet Ludwig at Coblenz, where the Emperor promised to help him against Philip ‘for seven years’, making Edward Vicar-General (or Deputy) of the Empire with jurisdiction over all Imperial fiefs outside Germany. In theory Edward could now summon as his vassals all the lords of the Low Countries and even the Counts of Burgundy and Savoy; in practice the post gave him hardly more than a dubious prestige. Nevertheless Edward and Philippa returned to Antwerp to hold court in the winter of 1338-1339 and ‘kept their house right honourably all that winter, and caused money, gold and silver, to be made at Antwerp, great plenty’.

If the English King was enjoying diplomatic triumphs, his country was enduring raids by enemy privateers. In March 1338 Nicolas Béhuchet and his sailors burnt all Portsmouth save for the parish church and a hospital. A few months later Hue Quiéret took five rich ships off Walcheren, including the great cog

Christopher

—‘richly laden with money and wool’—which had been built for Edward himself. In October 1338 Southampton went up in flames, then Guernsey was occupied. The following year the French raided from Cornwall to Kent, attacking Dover and Folkestone, putting the entire Isle of Wight to fire and sword, and even appearing in the Thames Estuary. French warships became an increasingly serious menace to the vessels which took wool to Flanders, and to the great wine fleet which every summer sailed between Southampton and Bordeaux. Furthermore, any English expedition to France had to reckon with being intercepted en route.

Christopher

—‘richly laden with money and wool’—which had been built for Edward himself. In October 1338 Southampton went up in flames, then Guernsey was occupied. The following year the French raided from Cornwall to Kent, attacking Dover and Folkestone, putting the entire Isle of Wight to fire and sword, and even appearing in the Thames Estuary. French warships became an increasingly serious menace to the vessels which took wool to Flanders, and to the great wine fleet which every summer sailed between Southampton and Bordeaux. Furthermore, any English expedition to France had to reckon with being intercepted en route.

In fact England was facing a full-scale invasion. Informed Englishmen had feared one by Philip’s Crusader fleet as early as 1333, and the raids of 1338-1340 caused grim rumours to circulate among the coastal folk—tales of kidnapped Kentish fishermen being mutilated and then paraded through the streets of Calais were not without foundation. A home-guard was organized for every southern county, the garde de la mer. On 23 March 1339, Philip VI issued an ordonnance for the conquest of England. Suggestions for the destruction of English merchant shipping (including even fishing boats) put forward by Béhuchet and costed as nearly as possible, were set aside—the ‘Grand Army of the Sea’ took precedence. Within little more than a year a fleet of over 200 vessels were assembling off Sluys on the Zeeland sea-coast, at the mouth of the river Zwyn. (In those days Sluys was an important seaport, though today the Zwyn has long been closed by silt.)

The English avenged the raids with gusto, sacking Le Treport in the spring of 1339. In the autumn of the same year they sailed into the harbour at Boulogne, burning thirty French ships at anchor, hanging their captains and leaving the lower town in flames. But the French invasion fleet continued to grow. Mille de Noyers, Marshal of France, planned to take 60,000 troops over the Channel.

Edward tried desperately to find enough money to fight Philip on land. His first expedition, in 1337—15,000 men under William de Bohun, Earl of Northampton, sent to harry the lands of the Count of Flanders—proved ruinously expensive. In 1339 he pawned the crown made for his coronation as King of France; he had already pawned the Great Crown of England. In September of that year he at last managed to invade France from the Low Countries in person, his troops consisting of a small English army which joined him at Antwerp, together with some noticeably unreliable German and Dutch mercenaries and the Duke of Brabant. He advanced slowly into Picardy, deliberately destroying the entire countryside of the Thiérache and besieging Cambrai. Philip moved up to meet him from Saint-Quentin with an army of 35,000 cavalry and foot.

King Edward, only too anxious to be attacked, drew up his army before Flamengerie in three lines; the English in front, the German princes and their men behind, and in third place the Duke of Brabant with his Brabançons and Flemings. (The English formation was dismounted men-at-arms in the centre and archers on the wings—obviously Edward hoped to employ the tactics he would use at Crécy six years later). Philip titillated the English lords’ appetite for chivalrous glory by issuing a challenge to trial by battle between the respective paladins of each army—a challenge which he then unsportingly withdrew. Still more damaging, he refused to fight at all, though his army outnumbered Edward’s by more than two to one. After a campaign of hardly more than a month, the English King was forced to retreat.

What makes the 1339 campaign of particular interest is the misery inflicted on French non-combatants. It was the custom of medieval warfare to wreak as much damage as possible on both towns and country in order to weaken the enemy government. The English had acquired nasty habits in their Scottish wars and during the campaign Edward wrote to the young Prince of Wales how his men had burnt and plundered ‘so that the country is quite laid waste of corn, of cattle and of any other goods’. Every little hamlet went up in flames, each house being looted and then put to the torch. Neither abbeys and churches nor hospitals were spared. Hundreds of civilians—men, women and children, priests, bourgeois and peasants—were killed while thousands fled starving to the fortified towns. The English King saw the effectiveness of ‘total war’ in such a rich and thickly populated land; henceforth the

chevauchée,

a raid which systematically devastated enemy territory, was used as much as possible in the hope of making the French sick of war. (Exactly the same principle inspired General Sherman’s March through Georgia four centuries later.) The English were obviously satisfied with what they had achieved on this occasion. One of Edward’s advisers, the great judge Sir Geoffrey Scrope, took a French cardinal ‘up a great and high tower, showing him the whole countryside towards Paris for a distance of fifteen miles burning in every place’. ‘Sir,’ asked Scrope, ‘does it not seem to you that the silken thread encompassing France is broken?’ At this, the cardinal fell down ‘as if dead, stretched out on the roof of the tower from fear and grief’.

chevauchée,

a raid which systematically devastated enemy territory, was used as much as possible in the hope of making the French sick of war. (Exactly the same principle inspired General Sherman’s March through Georgia four centuries later.) The English were obviously satisfied with what they had achieved on this occasion. One of Edward’s advisers, the great judge Sir Geoffrey Scrope, took a French cardinal ‘up a great and high tower, showing him the whole countryside towards Paris for a distance of fifteen miles burning in every place’. ‘Sir,’ asked Scrope, ‘does it not seem to you that the silken thread encompassing France is broken?’ At this, the cardinal fell down ‘as if dead, stretched out on the roof of the tower from fear and grief’.

Some more detached observers were equally horrified. Pope Benedict XII sent 6,000 gold florins to Paris for the relief of the refugees. The Archdeacon of Eu, who distributed the Papal bounty, left a report which speaks of 7,879 victims, mostly destitute, whom he relieved (though he does not give any estimate of the number of dead); nearly all were simple peasants or artisans. He tells of destruction by fire in 174 parishes, many of which had been entirely demolished together with their parish churches.

Edward now found himself even more alarmingly short of money than usual. After buying with his last remaining cash the alliance with Jacob van Artevelde, the King returned to England to try and find new funds, though he had to leave his children and pregnant wife at Ghent as surety for his debts. (His third son to survive, born at Ghent in his absence, was consequently named ‘John of Gaunt’.) The great historian of the Hundred Years War, Professor Edouard Perroy, writes how at this time, ‘anyone except Edward III would have been discouraged’.

Before leaving for England, Edward held an imposing assembly at Ghent on 6 February 1340. Here he publicly assumed the arms of France, quartering the golden lilies on their blue ground with his own gold lions on red, and styled himself King of France. (He is said to have done so on the advice of Jacob van Artevelde, who pointed out that by doing this he would become not merely the ally of the gallant Flemish pikemen but their King.) In addition Edward issued a cunningly worded proclamation addressed not only to the French lords but also to the common people of France ; he promised to ‘revive the good laws and customs which were in force in the time of St Louis our ancestor’, to reduce taxation and to stop debasing the coinage, and to be ‘guided by the counsel and advice of the peers, prelates, magnates and faithful vassals of the kingdom’. He was posing as a champion of local independence against Valois centralization, offering an alternative monarchy.

Edward then sent yet another insulting letter to Philip, challenging him to trial by battle as ‘we do purpose to recover the right we have to the inheritance which you so violently withhold from us’. The combat was to be either between the two kings—chivalrous but hardly fair as Philip was forty-seven and Edward only twenty-eight—or else between a hundred of Philip’s best knights and a hundred of Edward’s.

The challenge was never withdrawn, and henceforward Valois and Plantagenet were locked in an unrelenting struggle. Edward III had shown extraordinary determination and opportunism, even if he had failed to bring the French King to battle. In contrast Philip VI, now approaching old age by medieval standards, had remained entirely on the defensive. Despite his much advertised taste for the tournament, Philip successfully used a strategy of tempting Edward to invade and then refusing battle until the enemy’s money ran out.

2

Crécy 1340-1350

Therefore Valois say, wilt thou yet resign, Before the sickle’s thrust into the corn?

The Raigne of King Edward III

From battle and murder, and from sudden death, Good Lord, deliver us.

The Litany

The next stage of the Hundred Years War is the story of Edward III’s relentless perseverance despite setbacks both at home and abroad, and of how he was eventually rewarded. Blocked in Flanders, this dogged and rather terrifying man attacked in Brittany, in Guyenne, in Normandy and even in the Ile de Paris. First, however, he won a great victory at sea.

When the King arrived back in England from Ghent in the spring of 1340, he summoned Parliament and told it that unless new taxes were raised he would have to return to the Low Countries and be imprisoned for debt. Parliament made plain that it was very unhappy about Edward’s extravagance, but reluctantly granted him a ‘ninth’ for two years—the ninth sheaf, fleece and lamb from every farm, and the ninth part of every townsman’s goods. In return the King had to promise to abolish certain taxes and make a number of reforms in government. However he could now return to Ghent to redeem his wife and children and recommence operations against Philip. He collected reinforcements, assembling a fleet on the Suffolk coast for their transport. En route he intended to deal with the French armada at Sluys.

Contrary to what the chronicler Geoffrey le Baker seems to have heard, the King had been planning this move for some time. The enemy invasion fleet was now dauntingly large ; it included not only French but also Castilian and Genoese vessels, Castile being an ally of France while the Genoese were mercenaries under the veteran sea-captain Barbanera (or

‘Barbenoire’

as the French called him). Edward had requisitioned all the ships he could find, literally pressganging men to sail and to fight on them. Even so, his sailing masters, Robert Morley and the Fleming Jehan Crabbe, warned him that the odds were too high. The King accused them of trying to frighten him, ‘but I shall cross the sea and those who are afraid may stay at home’. On 22 June 1340 he finally set sail from the little port of Orwell in Suffolk, he himself on board his great cog

Thomas.

En route he was joined by Lord Morley, Admiral of the Northern Fleet, with fifty vessels—together their combined force amounted to 147 ships.

‘Barbenoire’

as the French called him). Edward had requisitioned all the ships he could find, literally pressganging men to sail and to fight on them. Even so, his sailing masters, Robert Morley and the Fleming Jehan Crabbe, warned him that the odds were too high. The King accused them of trying to frighten him, ‘but I shall cross the sea and those who are afraid may stay at home’. On 22 June 1340 he finally set sail from the little port of Orwell in Suffolk, he himself on board his great cog

Thomas.

En route he was joined by Lord Morley, Admiral of the Northern Fleet, with fifty vessels—together their combined force amounted to 147 ships.

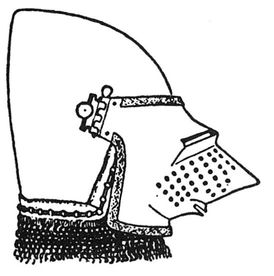

Probably these vessels were nearly all cogs. The English government had commissioned a number of converted cogs, the ‘King’s Ships’, which for all their shortcomings were intended for war. The cog was basically a merchant ship, designed for carrying cargoes which ranged from wool to wine and from livestock to passengers. Shallow-draughted and small-sized—usually 30 to 40 tons, though sometimes as big as 200—it could use creeks and inlets inaccessible to bigger ships. Clinker-built, broad-beamed and with a rounded bow and poop, it was a boat for all weathers and for the North Sea. But while the cog made an excellent troop transport, it was hardly a warship—even though special fighting tops could be built on the fore and stern castles. Tactics were brutally simple—to move to windward of the enemy ship and then try to sink her by ramming or by running her aground.

Other books

All That Is Solid Melts into Air by Darragh McKeon

Ruining You by Reed, Nicole

Indie Girl by Kavita Daswani

Edge of Solace (A Star Too Far) by Casey Calouette

WC02 - Never Surrender by Michael Dobbs

Blood Relative by Thomas, David

Sundown by Jade Laredo

Darling by Jarkko Sipila

The Third Magic by Molly Cochran

A Bride Worth Billions by Morgan, Tiffany