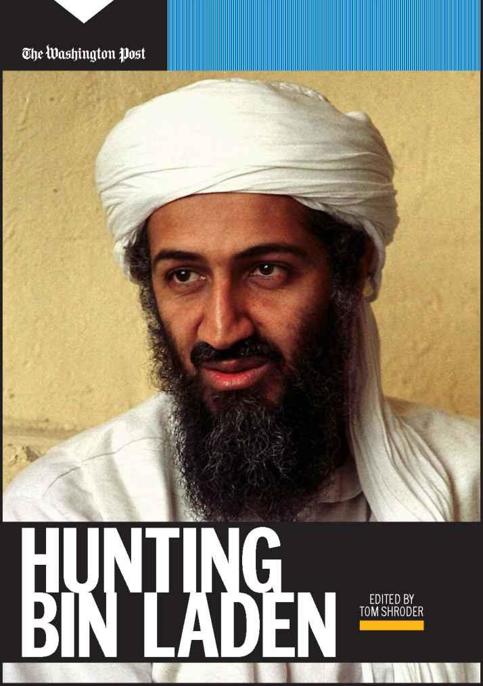

The Hunt for bin Laden

The Hunt for Bin Laden

Introduction

The long, secret campaign to track down Osama bin Laden has been called the biggest, costliest manhunt in history. It began in 1997 during the Clinton administration, when bin Laden was known as a jihadi money man, not a terrorist mastermind. As bin Laden issued increasingly explicit threats against the West, and America in particular, field CIA agents became convinced bin Laden posed a clear and present danger to the homeland. Time and again they had bin Laden in their cross-hairs only to have missions cancelled at the last moment by superiors in Langley and the White House.

As four hijacked commercial jets streaked toward their targets in New York and Washington, bin Laden was living comfortably in Afghanistan, trying to get a satellite signal to watch his handiwork on live TV. That evening, he toasted the collapsed towers at a collegial dinner, expressing pleasant surprise that the attack had killed so many. Then he went on the lam, touring strongholds of support in Afghanistan’s outback and making speeches. As the U.S. bombing campaign in Afghanistan began in earnest, bin Laden retreated to a complex of caves and tunnels dug into a mountainous region called Tora Bora. The CIA team hunting him had a solid fix on him there and concentrated huge blockbuster bombs on his location. But he escaped once more, and soon the war in Iraq drained the resources and diverted the spotlight from the hunt, turning the mission to kill or capture bin Laden into a back-burner operation and political liability for the Bush administration.

The hunt continued in the background for years without any solid leads as to where bin Laden had gone. The best guess put him in the almost lawless tribal regions on the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan, but the best guesses were wrong. As the treacherous attacks of 9/11 drifted almost a decade into the past, increasingly punishing drone attacks, interrogations of captured al Qaeda operatives and an ever expanding network of informants finally began to yield a trail, pebble by pebble.

It wasn’t until the Iraq war began to wind down that the search gained its endgame momentum, reclassified as a highest priority again by a new president. The breakthrough came when bin Laden’s shadowy courier was finally identified, and his cell phone intercepted. Wire intercepts and surveillance eventually led the CIA directly to a mysterious million-dollar compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. After fourteen years, two wars and billions of dollars spent in the effort, a team of Navy Seals finally brought the hunt to a swift and conclusive end.

This is a reconstruction of the hunt culled from reporting by more than two dozen Washington Post correspondents and staffers over more than 15 years.

From stories by:

John Ward Anderson, Peter Baker, Karin Brulliard, Steve Coll, Karen DeYoung, Michael Dobbs, Peter Finn, Marc Fisher, Bradley Graham, Anne E. Kornblut, John Lancaster, Richard Leiby, Vernon Loeb, Jerry Markon, Greg Miller, Molly Moore, Dana Priest, Ian Shapira, Ann Scott Tyson, Joby Warrick, Craig Whitlock, Scott Wilson and Bob Woodward.

Contributors:

William Branigin, Pamela Constable, Susan B. Glasser, John Lancaster, Allan Lengel, Colum Lynch, Ellen Nakashima, Walter Pincus, John Pomfret, Keith B. Richburg, Thomas E. Ricks, Paul Schwartzman, Robert E. Thomason, Josh White, Griff Witte and Kevin Sullivan; staff researcher Julie Tate; and special correspondents Haq Nawaz Khan and Kamran Khan.

Edited by Tom Shroder

One Manhunt Creates a Bigger One

The seeds of the CIA’s first formal plan to capture or kill Osama bin Laden were contained in another urgent manhunt — for Mir Aimal Kasi, the Pakistani migrant who murdered two CIA employees while spraying rounds from an assault rifle at cars idling before the entrance to the agency’s Langley headquarters in 1993.

For several years after the shooting, Kasi remained a fugitive in the border areas straddling Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran. From its Langley offices, the CIA’s Counterterrorist Center asked the Islamabad station for help recruiting agents who might be able to track Kasi down. Case officers signed up a group of Afghan tribal fighters who had worked for the CIA during the 1980s guerrilla war against Soviet occupying forces in Afghanistan.

The family-based team of paid agents, given the cryptonym FD/TRODPINT, set up residences around the city of Kandahar. They were rugged, bearded fighters — often in teams of a dozen or so — who rolled around southern Afghanistan in four-wheel-drive vehicles, blending comfortably into the region’s militarized tribal society.

When the TRODPINT team set out to find Kasi, one or two senior family members handled the face-to-face contacts with the CIA. Case officers working from the U.S. Embassy in Islamabad supplied them with cash, assault rifles, land mines, motorcycles, trucks, listening devices and secure communications equipment.

Together they concocted a bold plan to capture Kasi and fly him to the United States for trial. If the Afghan agents found Kasi, they would detain him until U.S. Special Forces secretly flew into Afghanistan to bundle the fugitive away. With the TRODPINT team acting as spotters, the CIA identified a desert landing strip near Kandahar that could be used for a clandestine American extraction flight. The White House approved the plan, and President Bill Clinton secretly dispatched a Special Forces team to southern Afghanistan to confirm the coordinates and suitability of the makeshift airstrip.

In the end, Kasi was found elsewhere. In late May 1997, an ethnic Baluch man walked into the U.S. Consulate in Karachi, Pakistan, and told a clerk that he had information about Kasi. He was taken to a young CIA officer, who was chief of base in the city. The informant handed her an application for a Pakistani driver’s license Kasi had filled out under an alias. It contained a photo and a thumbprint that confirmed Kasi’s identity.

Three weeks later, a team of CIA officers, Pakistani intelligence officers and FBI agents arrested Kasi at a hotel in Pakistan, flew him to the United States and jailed him for trial. (He was convicted of murder in 1997, sentenced to death in 1998 and executed in Virginia on Nov. 14, 2002.)

In the weeks that followed Kasi’s arrest, a new question was raised inside the CIA’s Counterterrorist Center: What would become of their elaborately equipped and financed TRODPINT assets? The agents had filed numerous reports about where Kasi might be, but none had panned out. Ultimately, the team played no direct role in Kasi’s arrest. Despite this questionable record, it seemed a shame to just cut them loose, some Langley officers believed.

At CIA headquarters, the unit set up to track Kasi was located in the Counterterrorist Center. A few partitions away was another small cluster of analysts and operators who made up what the CIA officially called the “bin Laden issue unit.”

The unit had been created early in 1996 to watch a troublesome supporter of radical Islamic jihad named Osama bin Laden, who was then living in Sudan.

The Beginnings of Bin Laden

Osama bin Laden’s father, Mohammed bin Laden, emigrated as a youth from the Hadramawt region of Yemen, arriving as a penniless laborer in 1925 in what would become the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Energetic and engaging, Mohammed bin Laden had a knack for engineering and found his way into the construction business.

By the late 1930s, he had established his own firm and was working on palaces for the royal family. In time, he became a favored contractor for the huge projects the kingdom undertook with its ever-growing oil riches.

He had already taken multiple wives and had more than a dozen children when, in 1956, he married 14-year-old Alia al-Ghanem, who came from a Syrian family of citrus farmers. In 1957, Alia gave birth to a son, Osama, which means “young lion” in Arabic.

He divorced Alia when Osama was a young boy and arranged for her to remarry Mohammed al-Attas, a mid-level administrator in the bin Laden company. Attas and Alia had four other children.

All the available testimony about Osama’s early years from relatives and friends portray him as a quiet, placid child whose favorite hobby was horseback riding. Despite the divorce and his life with a stepfamily, he remained a fully recognized member of the bin Laden clan.

He visited his father’s kin on weekends, joined the bin Laden family on outings and attended school with some of his half-brothers. He mourned with them when, in 1967, Mohammed bin Laden died in a plane crash in Saudi Arabia.

Osama bin Laden, who attended an elite private school in Jiddah — the al-Thager Model School — joined an after-school Islamic study group in eighth or ninth grade. In time, he adopted the beliefs and practices of an insistent piety, praying multiple times a day, letting his beard grow and arguing for a restoration of Islam in Arab politics.

Bin Laden continued this religious study after he entered Jeddah’s King Abdulaziz University in 1976, where he participated in the Muslim Brotherhood, an Islamist organization intent on imposing Koranic law throughout Muslim societies. But he remained quiet and deferential, focused on the search for a pure spiritual life. Only years later did his religiosity harden into a fanatical hatred.

He studied management and economics but never earned a university degree, leaving for a job with the bin Laden family business as a manager in Mecca. By that time, the company, headed by Osama’s older brother Salem, had been handed the enormous task of renovating the holy cities of Mecca and Medina.

At 17, bin Laden married his first wife: Najwa, a 14-year-old first cousin whom he had gotten to know during sojourns to Syria to visit his mother’s family. After university, he took a second and then a third wife, women who were better educated than his first. He would marry at least once more.

A Radical Turning Point

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in late 1979 profoundly influenced bin Laden’s course. Muslims around the world rallied to the Afghan cause, volunteering to help the mujaheddin resistance against the Soviet army. In the first years of the war, bin Laden served essentially as a philanthropic activist, traveling between the war front and Saudi Arabia with donations for the Afghan rebels.

During this period, he developed ties with a radical Palestinian professor of Islamic studies, Abdullah Azzam, who introduced him to the concept of transnational jihad. In 1984, bin Laden financed Azzam’s establishment in Peshawar, Pakistan, of a Services Office, which acted as a clearinghouse for information about the Afghan war and a vehicle for channeling recruits into Afghanistan.

In 1986, bin Laden moved his family to Peshawar and threw himself more actively into the war. He delivered his first known speech denouncing the United States for its support for Israel. It was in Peshawar, too, that bin Laden met members of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, most notably Ayman al-Zawahiri, a surgeon who had spent time in Cairo prisons on conspiracy charges. Zawahiri would become the senior deputy in bin Laden’s terrorist movement.

Dissatisfied with merely financing the struggle against the Soviets, bin Laden decided to build his own small Arab militia in the mountains along the Afghan-Pakistani border. Near Jaji in eastern Afghanistan, he constructed a camp called the Lion’s Den.

Even more significant for the resistance effort was his construction work. Using equipment supplied by his family’s firm, he helped build roads north toward Tora Bora, a mountainous region in eastern Afghanistan, and a warren of caves to serve as shelters and arms depots.

When Soviet troops attacked bin Laden’s camp in the spring of 1987, he and his band of Arab volunteers battled back, earning him recognition as a fighter and not just a bankroller and proselytizer of jihad.

Even after Moscow announced plans in 1988 to begin withdrawing from Afghanistan, bin Laden hoped to develop a larger Arab force and employ it in a broader jihad.

Giving this new Islamic entity a name, he and associates decided to call it al-Qaeda al-Askariya, or “the Military Base.”

But in late 1989, with ethnic Afghan factions fighting increasingly among themselves, bin Laden moved back to Saudi Arabia. His brother Bakr, who had taken over leadership of the bin Laden family holdings after the death of Salem in a plane accident in Texas the year before, was about to oversee a major corporate reorganization and inheritance distribution. By then, the family business had expanded into an international conglomerate, with projects around the world and interests in industrial and power contracts, oil exploration, mining and telecommunications.

As part of a one-time distribution to Mohammed bin Laden’s heirs, Osama reportedly received about $8 million in cash in 1989. He reinvested the rest of his inheritance in new partnerships set up by Bakr, acquiring shares valued at about $10 million.

Such wealth, while significant, amounted to far less than the huge fortune sometimes attributed to bin Laden. According to journalist Steve Coll in his book “The Bin Ladens,” the stream of regular dividends and salaries that flowed to Osama from the early 1970s to the early 1990s averaged slightly more than $1 million a year.

Although bin Laden no doubt funded some of al-Qaeda’s development from his own pocket, a more significant portion of the financing probably came from the prodigious ability he had demonstrated during the Afghan war to raise funds through a complex web of charities, donors and proselytizing networks.

Bin Laden’s return to Saudi Arabia led to serious strains with government authorities; Saudi officials took issue with his support for Islamist rebels in Yemen. Bin Laden, in turn, grew deeply irritated with King Fahd’s willingness to accept U.S. troops on Saudi soil in the war ousting Iraqi troops from Kuwait.

In the middle of 1991, bin Laden was forced out of Saudi Arabia. He settled in Sudan, whose ruler, Hassan al-Turabi, shared bin Laden’s dream of establishing a purist Islamic state and had courted his investment. Bin Laden proceeded to establish a number of legitimate businesses but also began laying the groundwork for a global terrorist network.

During this period, al-Qaeda turned from being the anti-communist Islamic army that bin Laden conceived into a terrorist organization bent on attacking the United States. As the 9/11 Commission Report later recounted, bin Laden, while in Khartoum, enlisted groups from across the Middle East, Africa and Southeast Asia. He provided equipment and training assistance to terrorists in the Philippines, aided insurrectionists in Kashmir, assisted Islamists in Tajikistan and maintained connections in the Bosnian conflict.

His siblings publicly repudiated him in February 1994 after trying to persuade him to cease his militant activities and return to Saudi Arabia. His shares in the family businesses were sold, and he was cut off from all dividend and loan payments. Saudi Arabia revoked bin Laden’s citizenship.

Under pressure from the Saudis, Americans and others to do something about bin Laden, Sudanese authorities forced him out in May 1996 and seized a number of his personal assets. Moving to the Afghan city of Jalalabad, bin Laden released a long document declaring war against the United States, the first document he published that formally endorsed a violent campaign aimed at Western interests.

Afghanistan was a considered choice for bin Laden’s new base. The CIA had no station or base in Afghanistan, and it had no paid agents in the country at the time, other than those hunting for Kasi near Kandahar and a few loose contacts working on drug trafficking and recovering Stinger shoulder-fired missiles, according to Tom Simons, then the U.S. ambassador to Pakistan, whose account is supported by several other U.S. officials familiar with the CIA’s Afghan agent roster.