The Ian Fleming Miscellany (10 page)

Read The Ian Fleming Miscellany Online

Authors: Andrew Cook

It is pretty enough now. Chris Blackwell, who has known it all his life, has it. But in the 1940s locals watched with relief as vegetation rambled all over and covered it.

Reggie found him a live-in cook-housekeeper, Violet, a comfortable woman. Ian would get up early and swim. After an excellent breakfast of paw paw, Blue Mountain coffee, scrambled eggs, and bacon, he would read. At around midday, he swam and snorkelled and looked for lobsters for lunch. Ackee and saltfish, curried goat and grilled snapper were Violet's repertoire, and he liked them all.

Among the first visitors, in 1947, were his mother and his half-sister Amaryllis. Eve was fascinated by Jamaica, since Augustus John had been inspired by it before the war. Amaryllis gave a recital with piano accompaniment by Miss Foster Davis, whom they invited to lunch afterwards at the Myrtle Bank Hotel. All the other guests in the room got up and left when the Flemings and Miss Davis were shown to a table. They were white, and Miss Foster Davis was not. Eve, furious, whispered to her âtake no notice'. Amaryllis recounted this shameful incident and said later that it was one of the few times she'd been proud of her mother.

They were unprepared for the rigours of Goldeneye, with its forbidding aspect and the legs of the beds standing in jars of water to keep ants out; they weren't crazy about Violet's curried goat, either. They fled to the Montego Bay Hotel and ran into Noël Coward, who sympathised.

Ian was 40ish, with some health issues, but still smoking sixty or seventy cigarettes a day. He had done so for twenty years at least. He would carry on smoking at the same rate. So to imagine him eating or reading or even swimming is to remember that he punctuated his every activity by lighting, smoking, waving around and stubbing out cigarettes. There was always a pack by his side.

He was the least considerate of hosts. He would set off in the mornings with Anne in a boat and not return until the evening. Loelia, playing gooseberry back in the blockhouse, had nothing to do except read, and despite her vast financial resources lacked the will to find anything. In the end she too packed and left for a hotel.

Ian had other visitors. Jamaica â with Coward living there, and Lord Beaverbrook, William Stephenson and Tommy Leiter, who had become friends with Ian in Washington â was increasingly attracting wealthy individuals. Ivar Bryce had married the fabulously wealthy Jo Hartford. Her brother owned Paradise Island in the Bahamas. She had an exquisite old house in Nassau as well as a place in New York State on the border with Vermont. In 1949 they decided to take a Caribbean cruise with some friends. On the way they would call in at Goldeneye, where Ian was in residence with a girlfriend.

Their party disembarked in Oracabessa Harbour. The friends were taken to a hotel while Jo and Ivar left for Goldeneye. Later that night, returning from dinner along the coast in Ocho Rios, they passed the captain on shore amid an agitated crowd â the entire population of Oracabessa â and their yacht, wrecked, in the harbour.

The sorry story was told. Unknown to the passengers, in the first days of the trip down the east coast, it became evident to the captain and engineer that the yacht company had hired a bunch of clowns to crew with them and they were the only people who knew how to run the ship. All the way here, they'd had to take entire responsibility for the yacht's safe journey. Ocorabessa had been the one night when they knew the visitors wouldn't be coming back. Both captain and engineer took their chance to go ashore. The crew, in a ship moored in a calm harbour, would look after it. What could possibly go wrong? It had occurred to neither of them that the crew might raid the bar, drink it dry and smash the boat up.

This was the night, over a nightcap later when the women were in bed, when Fleming told Ivar that he was planning to write his first book. He'd been thinking about it since he was a schoolboy. It would be a spy story and the hero would be a British secret agent.

Anne usually went to Jamaica when Ian did but they would leave and arrive separately. In 1949, her departure had been noticed in the newspapers. When she got off the boat from New York at Southampton on her way back, a man served her with a âcease and desist' notice from Esmond. She was married to Lord Rothermere and had to stop seeing Ian Fleming. âBut,' she protested to her friends, âhe knows Ian Fleming has been my lover for fourteen years.'

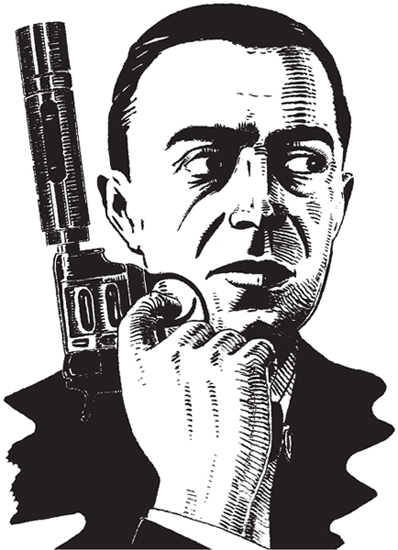

SHOTGUN

![]()

WO

B

IG

S

TEPS

â¢

In the first month of 1952, Ian told Amaryllis that as soon as Anne's divorce came through, he would marry her. Amaryllis was appalled. She disliked Anne, and they both knew it. He told her there was no alternative. Anne was pregnant. She and Esmond had been separated since October, so the child was his. He didn't tell her that in 1948 Anne had had a baby which didn't live, which had been his too. Esmond Rothermere knew, even then, but not until the âcease and desist' notice did he take any action.

Ian was enough of a Fleming to consider the future from every financial angle. He had always wanted, and with a child on the way actively needed, to make a lot of money. He had once said that his ideal woman would be about 30, kind, Jewish and with an independent income. A younger version of Maud and Liesl, in fact.

The âreal James Bond', the American ornithologist whose book

Field Guide to Birds of the West Indies

gave Fleming the name for his own âMaster-spy'.

Philadelphia Enquirer

Anne was 38 and came encumbered by extravagant tastes plus two school-age children by Shane O'Neill. She looked what people call âhard-faced', and the tight little hairstyles, vivid lipstick and rigidly tailored clothing of that era didn't help. âShe really is very handsome and well-bred, but no sex appeal,' observed Barbara Skelton.

But they were to marry March 1952, and he would have to write the book. Now. He thought about how to do it and worked out, as he always did, a plan. The idea of writing a spy novel had apparently been in Fleming's mind for a decade before he finally decided to commit the book to paper. Little did he know the phenomenon he was about to create when he sat down behind his typewriter on the morning of 15 January 1952 to start the first chapter of

Casino Royale

. Working alone at âGoldeneye' there would be no distractions. He knew the plot and the characters; he had been thinking about them for years, deliberately noting aspects of people he had met, especially during the war. He would type 2,000 words five days a week for six to eight weeks. He would work in the mornings and under no circumstances stop to look anything up. In the evening he'd make corrections. On the shelf in his study was the book that had gifted him the name of his hero,

Field Guide to Birds of the West Indies

, by the ornithologist James Bond.

Fleming told Leonard Mosley, a contemporary at

The Sunday Times

, that he had created James Bond as the result of reading about the exploits of the British secret agent Sidney Reilly in the archives of the British Intelligence Service during the war. He had apparently learnt a great deal about the operational history of NID from the departmental archive, including its role in the greatest intelligence coup of World War One â the cracking of the German diplomatic code 0070, which possibly gave him the inspiration for Bond's own code number 007. His interest in and knowledge of NID case files from World War One enabled him to draw on a rich seam of characters, experiences and situations that would prove invaluable in creating the fictional world of James Bond.

Sidney Reilly, from the 1931

Evening Standard

serial âMasterspy'.

Evening Standard

One of Fleming's wartime contacts, for example, had been Charles Fraser-Smith, a seemingly obscure official at the Ministry of Supply. In reality, Fraser-Smith provided the intelligence services with a range of fascinating and ingenious gadgets such as compasses hidden inside golf balls and shoelaces that concealed saw blades. He was the inspiration for Fleming's Major Boothroyd, better known as âQ' in the Bond novels and films.

Having a fascination for gadgets, deception and intrigue, Fleming had always been particularly attracted to the âblack propaganda' work undertaken by the Political Warfare Executive, headed by former diplomat and journalist Robert Bruce Lockhart, with whom he also struck up an acquaintance. In 1918 Lockhart had worked with Sidney Reilly in Russia, where they became embroiled in a plot to overthrow Lenin's fledgling government. Within five years of his disappearance in Soviet Russia in 1925, the press had turned Reilly into a household name, dubbing him a âMaster Spy' and crediting him with a string of fantastic espionage exploits.

Fleming had therefore long been aware of Reilly's mythical reputation and no doubt listened in awe to the recollections of a man who had not only known Reilly personally but was actually with him during the turmoil and aftermath of the Russian Revolution. Lockhart had himself played a key role in creating the Reilly myth in 1931 by helping Reilly's wife Pepita publish a book purporting to recount her husband's adventures. As a Beaverbrook journalist at the time, Lockhart also had a hand in the deal that led to the serialisation of Reilly's âMaster Spy' adventures in the

London Evening Standard

.

He stuck to the plan. The first draft must be written fast. As he wrote in Jamaica he absolutely must not allow himself to be sidelined into research or concerned by detail.

He stuck to a formula. He had read dozens of books of the kind he wanted to write. He instinctively knew the general structure of a thriller, the need for a dramatic dilemma, big action scenes, reversals of fortune and suspense before a triumphant outcome. He knew the essential characters. As a schoolboy he'd read John Buchan and âSapper' and William le Queux, and knew he needed a patriotic protagonist who was a braver, better-looking, more accomplished version of the reader, and a lethal antagonist about whom everything was alien. But all that

Boy's Own

stuff was from the 1920s. He'd got to add plenty of sex to make it work for the fifties â like Harold Robbins with

Never Love a Stranger

. There must be women, impossibly seductive and if possible bound and gagged as on the lurid covers of

True Detective

. And â because the British audience were living in a grey world â a strong dose of material aspiration. The British were riveted by enormous wealth.

Daily Express

readers were fixated on Lord and Lady Docker because of Bernard Docker's enormous yacht and astonishing Daimler with hydraulically operated hood, and his wife's mink and diamonds, former husbands and seamy past as a showgirl. The same people read the William Hickey column because it was about aristocrats who turned up at race meetings and parties. Cars, hotels, beaches, women: James Bond must consume them all, conspicuously.