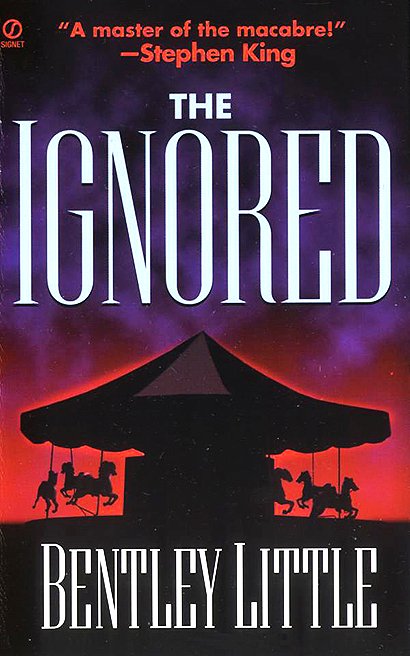

The Ignored

Authors: Bentley Little - (ebook by Undead)

THE IGNORED

(An Undead Scan v1.0)

Thanks, as always, to my friends and family.

Special thanks to the employees of the City of Costa Mesa with whom I worked from 1987 to 1995:

both the friendly intelligent competent professionals I liked, and the small-minded backbiting

bureaucratic assholes I hated.

PART ONE

Ordinary Man

ONE

On the day I got the job, we celebrated.

I’d been out of school for nearly four months, and I’d almost given up

hope of ever finding employment. I’d graduated from UC Brea in December with a

BA in American Studies—not the world’s most practical major—and I’d been

looking for a job ever since. I’d been told more than once by my professors and

my advisor that American Studies was ideal for someone attempting to start a

career, that the “interdisciplinary course work” would make me more desirable to

prospective employers and more valuable in today’s job market than someone with

more narrow, specialized knowledge.

That was bullshit.

I’m sure the professors at UC Brea didn’t intentionally try to sabotage

my life. I’m sure they really did think that a degree in American Studies was as

valuable to people in the outside world as it was to them. But the end result of

my misdirected education was that no one wanted to hire me. On

Donahue

and

Oprah

, representatives from major corporations said in panel

discussions that they were looking for well-rounded individuals, not just

business majors but liberal arts majors. But the PR they fed to the public

through the media and what really went on were two different things. Business

majors were being hired right and left—and I was still working part-time at

Sears, selling men’s clothing.

It was my own fault, really. I’d never known what I wanted to do with my

life or how I wanted to earn my living. After finishing my General Ed

requirements, I’d drifted into American Studies because the department’s courses

that semester had sounded interesting and fit easily into my work schedule at

Sears. I gave no thought whatsoever to my career, to my future, to what I wanted

to do after I graduated. I had no goals, no plans; I just sort of took things as

they came, and before I knew it, I was out.

Maybe some of that came across in my job interviews. Maybe that’s why I

hadn’t been hired yet.

It certainly didn’t show up on my resume, which was professionally

typeset and, if I do say so myself, damned impressive.

I’d seen the notice for this job opening at the Buena Park Public

Library. There was a big binder that contained flyers and notices for all sorts

of government agencies, public institutions, and private corporations, and I’d

been checking it out each Monday, after notices for the coming week were added.

The jobs listed at the library seemed to be of a higher quality than those in

the want ads of the

Register

or the

Los Angeles Times

, and

anything was better than the so-called Career Center at UC Brea.

This position, listed under the heading “Business and Corporations,” was

for some sort of technical writer, and the requirements looked promisingly

nonspecific. No previous experience was necessary, and the only hard-and-fast

rule seemed to be that all applicants have a bachelor’s degree in Business,

Computer Science, English, or Liberal Arts.

American Studies was nearly Liberal Arts, so I wrote down the name of

the company and the address, and after driving back to the apartment and leaving

a note for Jane on the refrigerator, I drove out to Irvine.

The corporation was a huge faceless building in a block of huge faceless

buildings. I walked through the massive lobby and, following the directions of a

security guard at the front desk, to the elevator that led to the personnel

department. There I was given a form, a clipboard, and a pen, and I sat down in

a comfortably padded office chair to fill out my application. I had already

decided in my own mind that I would not get this job, but I dutifully filled out

the entire application and turned it in.

A week later, I received a notice in the mail informing me that I had

been scheduled for an interview on the coming Wednesday at one-thirty.

I didn’t want to go, and I told Jane I didn’t want to go, but Wednesday

morning found me calling in sick to Sears and ironing my one white shirt on a

towel on the kitchen table.

I arrived for the interview a half hour early, and after filling out

another form, I was given a printed description of the position and led by a

personnel assistant down a hall to the conference room where interviews were

being conducted. “There’s one applicant ahead of you,” the assistant told me,

nodding toward a closed door. “Have a seat, and they’ll be with you shortly.”

I waited on a small plastic chair outside the door. I had been advised

by the people at the Career Center to always plan ahead what I was going to say

in a job interview, to think of all the questions that I might be asked and come

up with a prepared answer for each, but hard as I tried, I could think of

nothing that might be asked of me. I leaned back, close to the door, and

listened carefully, trying to hear what was being asked of my rival inside the

room so I could learn from his mistakes. But the door was soundproof and kept in

all noise.

So much for planning my answers.

I looked around the hallway. It was nice. Wide, spacious, with lots of

light. The tan carpet was clean, the white walls recently painted. A pleasant

working environment. A young, well-dressed woman carrying a sheaf of papers in

her hand emerged from a doorway down the hall, passing by me without a glance.

I was nervous, and I could feel sweat trickling in twin rivulets from

under my arms down the sides of my body. Thank God I’d worn a suit with a

jacket. I glanced down at the paper in my hand. The description of the job’s

educational requirements was clear—I didn’t have to worry about that—but

the actual responsibilities of the position were vague, couched in

indecipherable bureaucratese, and I realized that I did not really know anything

about the job for which I was applying.

The door opened, and a handsome, business-suited man several years my

senior strode out. He had a professional demeanor, his hair was short and neatly

trimmed, and he carried in his hand a leather portfolio. This was who I was

competing against? I suddenly felt ill-prepared, shabby in my appearance and

amateurish in my attitude, and I knew with unarguable certainty that I was not

going to get the job.

“Mr. Jones?”

I looked up as my name was called.

An older Asian woman was holding the door open. “Would you step in,

please?”

I stood, nodded, and followed her into the conference room. She motioned

toward three men seated at a long table in the front of the room, and promptly

sat down on a chair next to the door.

I walked forward. The men looked forbidding. All three were wearing

nearly identical gray suits, and none of them were smiling. The one on the right

was the oldest, a heavyset gray-haired man with a severely lined face and thick

black-framed glasses, but it was the youngest man, in the center, who appeared

to be in charge of the proceedings. He had a pen in his hand, and on the table

before him was a stack of applications identical to the one I had submitted. The

short man on the left seemed to take no notice of my entrance and was staring

disinterestedly out the window of the room.

The middle man stood, smiled, and offered me his hand, which I shook.

“Bob?” he said.

I nodded.

“Glad to meet you, I’m Tom Rogers.” He motioned for me to sit in the

lone chair in front of the table and sat down himself.

I felt a little better. Despite the formality of his attire, Rogers had

about him a distinctly informal air, a casually relaxed way of speaking and

moving that immediately put me at ease. He was also not that much older than me,

and I figured that might be a point in my favor.

Rogers glanced down for a moment at my application and nodded to

himself. He smiled up at me. “You certainly look good here. Oh, I almost forgot,

this is Joe Kearns from Personnel.” He nodded toward the small man staring out

the window. “And this is Ted Banks, head of Documentation Standards.” The older

man nodded brusquely.

Rogers picked up another sheet of paper. Through its translucent back, I

could see lines of type. Questions, I assumed.

“Have you written any computer documentation before?” Rogers asked.

I shook my head. “No.” I thought it was best to be blunt and to the

point. Maybe I’d get extra credit for honesty.

“Are you familiar with SQL and D-Base?”

The questions went on from there, not straying far from those technical

lines. I knew right away that I would not get the job—I had never even

heard

most of the computer terms that were being bandied about—but I

stuck it out to the end, bravely trying to play up my broad educational

background and strong writing skills. Rogers stood, shook my hand, smiled, and

said they’d let me know. The other two men, who had remained silent throughout

the interview, said nothing. I thanked them for their time, made an effort to

nod to each, and left.

My car died on the way home.

It was a bad end to a bad day, and I can’t say that I was surprised. It

seemed somehow appropriate. So many things had gone so wrong for so long that

what would have once sent me into paroxysms of panic now did not even phase me.

I just felt tired. I got out of the car and, with the door open and one hand on

the steering wheel, pushed it to the side of the street, out of traffic. The car

was a piece of crap, had been a piece of crap since the day I’d bought it from a

now defunct used-car lot, and part of me was tempted to leave it where it was

and walk off. But, as always, what I wanted to do and what I actually did were

two different things.

I locked the car and walked across the store to a 7-Eleven to call AAA.

It wouldn’t have been so bad, I suppose, if I hadn’t been so far away

from home, but my car had died in Tustin, a good twenty miles from Brea, and the

belligerent Neanderthal who was sent out by AAA to tow my car said that he was

authorized to bring my car to any mechanic within a five-mile radius but that

anything beyond that would cost me $2.50 a mile.

I didn’t have any money, but I had even less patience, and I told him to

take my car to the Sears in Brea. I’d charge the tow, charge the auto work, and

hitch a ride home from someone.

I got home at the same time as Jane. I gave her a thumbnail sketch of my

day, let her know I wasn’t in the mood to talk, and spent the rest of the

evening lying on the couch silently watching TV.

They called late Friday afternoon.

Jane answered the phone, then called me over. “It’s the job!” she

whispered.

I took the receiver from her. “Hello?”

“Bob? This is Joe Kearns from Automated Interface. I have some good news

for you.”

“I got the job?”

“You got the job.”

I remembered Tom Rogers, but I didn’t know which of my nonspeaking

interviewers was Joe Kearns. It didn’t matter, though. I’d gotten the job.

“Can you come in Monday?”

“Sure,” I said.

“I’ll see you then, then. Come on up to Personnel and we’ll get the

formalities straightened out.”

“What time?”

“Eight o’clock.”

“Should I wear a suit?”

“White shirt and tie will be fine.”

I felt like dancing, like jumping, like screaming into the phone. But I

just said, “Thank you, Mr. Kearns.”

“We’ll see you Monday.”

Jane was staring at me expectantly. I hung up the phone, looked at her,

and grinned. “I got it,” I said.

We celebrated by going to McDonald’s. It had been a long time since we’d

gone out at all, and even a trip like this seemed a luxury. I pulled into the

parking lot and looked over at Jane. I made my voice sound as British and

snobbish as I could, given my complete lack of any dramatic talent: “The

drive-thru, madam?”

She caught on and looked at me with a superior and slightly disapproving

tilt of her head. “Certainly not,” she sniffed. “We will dine indoors, in the

dining room, like civilized human beings.”

We both laughed.

As we walked into McDonald’s, I felt good. The air outside was cool, but

inside, the restaurant was warm and cozy and smelled deliciously of french

fries. We decided to splurge—cholesterol be damned—and we each ordered Big

Macs, large fries, large Cokes, and apple pies. We sat on plastic seats in a

four-person booth next to a life-sized statue of Ronald McDonald. There was a

family in one of the adjoining booths—a mom and dad taking their uniformed

young son for a post-Pop Warner treat—and watching them eat over Jane’s

shoulder made me feel comfortably relaxed.