The Illusion of Conscious Will (12 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

If there really were such a thing as the psychokinetic powers imagined in the movies, people who had them would experience something very much like this. When Sissy Spacek in

Carrie

burned down the high school gym, for example, or when John Travolta in

Phenomenon

moved small objects into his hands from a distance, it would certainly be as easy for them to ascribe these results to their own will as would be your act of moving a tree branch at a distance. If there really were people with such occult abilities, they probably would have exactly the same kind of information that you have about your branch. They would know in advance when something was going to happen, and they would be looking in that direction and thinking about it when it did happen. The feeling that one is moving the tree branch surfaces in the same way that these folks would get the sense that they could create action at a distance. All it seems to take is the appropriate foreknowledge of the action. Indeed, with proper foreknowledge it is difficult

not

to conclude one has caused the act, and the feeling of doing may well up in direct proportion to the perception that relevant ideas had entered one’s mind before the action. This is beginning to sound like a theory.

A Theory of Apparent Mental Causation

The experience of will could be a result of the same mental processes that people use in the perception of causality more generally. The theory of apparent mental causation, then, is this:

People experience conscious will when they interpret their own thought as the cause of their action

(Wegner and Wheatley 1999).

1

This means that people experience conscious will quite independently of any actual causal connection between their thoughts and their actions. Reductions in the impression that there is a link between thought and action may explain why people get a sense of involuntariness even for actions that are voluntary—for example, during motor automatisms such as table turning, or in hypnosis, or in psychologically disordered states such as dissociation. And inflated perceptions of the link between thought and action may, in turn, explain why people experience an illusion of conscious will at all.

The person experiencing will, in this view, is in the same position as someone perceiving causation as one billiard ball strikes another. As we learned from Hume, causation in bowling, billiards, and other games is inferred from the constant conjunction of ball movements. It makes sense, then, that will—an experience of one’s own causal influence—is inferred from the conjunction of events that lead to action. Now, in the case of billiard balls, the players in the causal analysis are quite simple: one ball and the other ball. One rolls into the other and a causal event occurs. What are the items that seem to click together in our minds to yield the perception of will?

1.

The Wegner and Wheatley (1999) paper presented this theory originally. This chapter is an expanded and revised exposition of the theory.

One view of this was provided by Ziehen (1899), who suggested that thinking of self before action yields the sense of agency. He proposed, “We finally come to regard the ego-idea as the cause of our actions because of its very frequent appearance in the series of ideas preceding each action. It is almost always represented several times among the ideas preceding the final movement. But the idea of the relation of causality is an empirical element that always appears when two successive ideas are very closely associated” (296).

And indeed there is evidence that self-attention is associated with perceived causation of action. People in an experiment by Duval and Wicklund (1973) were asked to make attributions for hypothetical events (“Imagine you are rushing down a narrow hotel hallway and bump into a housekeeper who is backing out of a room”). When asked to decide who was responsible for such events, they assigned more causality to them-selves if they were making the judgments while they were self-conscious. Self-consciousness was manipulated in this study by having the participants sit facing a mirror, but other contrivances, such as showing people their own video image or having them hear their tape-recorded voice, also enhance causal attribution to self (Gibbons 1990).

This tendency to perceive oneself as causal when thinking about one-self is a global version of the more specific process that appears to under-lie apparent mental causation. The specific process is the perception of a causal link not only between self and action but between one’s own thought and action. We tend to see ourselves as the authors of an act primarily when we have experienced relevant thoughts about the act at an appropriate interval in advance and so can infer that our own mental processes have set the act in motion. Actions we perform that are not presaged in our minds, in turn, would appear not to be caused by our minds. The intentions we have to act may or may not

be

causes, but this doesn’t matter, as it is only critical that we

perceive

them as causes if we are to experience conscious will.

In this analysis, the experience of will is not a direct readout of some psychological force that causes action from inside the head. Rather, will is experienced as a result of an interpretation of the

apparent

link between the conscious thoughts that appear in association with action and the nature of the observed action

. Will is experienced as the result of self-perceived apparent mental causation

. Thus, in line with several existing theories (Brown 1989; Claxton 1999; Harnad 1982; Hoffman 1986; Kirsch and Lynn 1997; Langer 1975; Libet 1985; Prinz 1997; Spanos 1982; Spence 1996), this theory suggests that the will is a conscious experience that is derived from interpreting one’s action as willed. Also in line with these theories, the present framework suggests that the experience of will may only map rather weakly, or at times not at all, onto the actual causal relation between the person’s cognition and action. The new idea introduced here is the possibility that the experience of acting develops when the person infers that his or her own

thought

(read: intention, but belief and desire are also important) was the cause of the action.

This theory makes sense as a way of seeing the will because the causal analysis of anything, not only the link from thought to action, suffers from a fundamental uncertainty. Although we may be fairly well convinced that A causes B, for instance, there is always the possibility that the regularity in their association is the result of some third variable, C, which causes both A and B. Drawing on the work of Hume, Jackson (1998) reminds us that “anything can fail to cause anything. No matter how often B follows A, and no matter how initially obvious the causality of the connection seems, the hypothesis that A causes B can be over-turned by an over-arching theory which shows the two as distinct effects of a common underlying causal process” (203). Although day always precedes night, for example, it is a mistake to say that day

causes

night, because of course both are caused in this sequence by the rotation of the earth in the presence of the sun.

This uncertainty in causal inference means that no matter how much we are convinced that our thoughts cause our actions, it is still true that both thought and action could be caused by something else that remains unobserved, leaving us to draw an incorrect causal conclusion. As Searle (1983) has put it, “It is always possible that something else might actually be causing the bodily movement we think the experience [of acting] is causing. It is always possible that I might think I am raising my arm when in fact some other cause is raising it. So there is nothing in the experience of acting that actually guarantees that it is causally effective” (130). We can never be sure that our thoughts cause our actions, as there could always be causes of which we are unaware that have produced both the thoughts and the actions.

This theory of apparent mental causation depends on the idea that consciousness doesn’t know how conscious mental processes work. When you multiply 3 times 6 in your head, for example, the answer just pops into mind without any indication of how you did that.

2

As Nisbett and Wilson (1977) have observed, the occurrence of a mental process does not guarantee the individual any special knowledge of the mechanism of this process. Instead, the person seeking self-insight must employ a priori causal theories to account for his or her own psychological operations. The conscious will may thus arise from the person’s theory designed to account for the regular relation between thought and action. Conscious will is not a direct perception of that relation but rather a feeling based on the causal inference one makes about the data that do become avail-able to consciousness—the thought and the observed act.

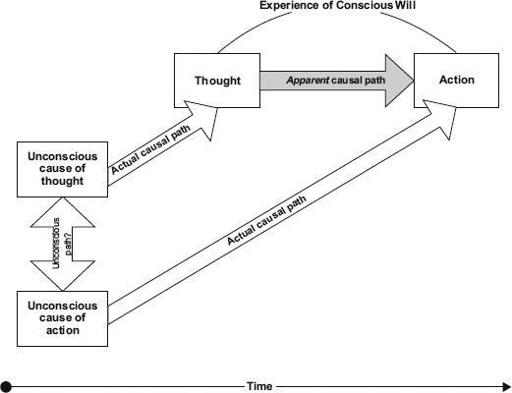

A model of a mental system for the production of an experience of conscious will based on apparent mental causation is shown in

figure 3.1.

The model represents the temporal flow of events (from left to right) leading up to a voluntary action. In this system, unconscious mental processes give rise to conscious thought about the action (e.g., intention, belief), and other unconscious mental processes give rise to the voluntary action. There may or may not be links between these underlying unconscious systems (as designated by the bidirectional unconscious potential path), but this is irrelevant to the perception of the

apparent

path from conscious thought to action. Any actual path here cannot be directly perceived, so there may be no actual path. Instead, it is the perception of the apparent path that gives rise to the experience of will: When we think that our conscious intention has caused the voluntary action that we find ourselves doing, we feel a sense of will. We have willfully done the act.

3

2.

If you were trying to multiply something harder, say, 18 times 3, in your head, you might have a number of steps in the computation come to mind (3 times 8 is 24, and then . . .), and so you could claim to be somewhat conscious of the mechanism because you could report the results of subparts of the process. Extended mental processes that are not fully automatic often thrust such “tips of the ice-berg” into consciousness as the process unfolds and so allow for greater confidence in the inferences one might make about their course (Ericsson and Simon 1984; Vallacher and Wegner 1985). In the case of willing an action, however, there do not seem to be multiple substeps that can produce partial computational results for consciousness. Rather, we think it and do it, and that’s all we have to go on. If we perform an action that we must “will” in subparts, each subpart is still inscrutable in this way.

Figure 3.1

The experience of conscious will arises when a person infers an apparent causal path from thought to action. The actual causal paths are not present in the person’s consciousness. The thought is caused by unconscious mental events, and the action is caused by unconscious mental events, and these unconscious mental events may also be linked to each other directly or through yet other mental or brain processes. The will is experienced as a result of what is apparent, though, not what is real.

How do we go about drawing the inference that our thought has caused our action? The tree branch example yields several ideas about this. Think, for instance, of what could spoil the feeling that you have moved the branch. If the branch moved before you thought of its moving, for instance, there would be nothing out of the ordinary, and you would experience no sense of willful action.

4

The thought of movement would be interpretable as a memory or even a perception of what had happened. If you thought of the tree limb’s moving and then something quite different moved (say, a nearby chicken dropped to its knees), again there would be no experience of will. The thought would be irrelevant to what had happened, and you would see no causal connection. And if you thought of the tree limb’s moving but noticed that something other than your thoughts had moved it (say, a squirrel), no will would be sensed. There would simply be the perception of an external causal event. These observations point to three key sources of the experience of conscious will—the

priority, consistency,

and

exclusivity

of the thought about the action (Wegner and Wheatley 1999). For the perception of apparent mental causation, the thought should occur before the action, be consistent with the action, and not be accompanied by other potential causes.

3.

The experience of will can happen before, during, or after the action. So, it is probably the case that the inference system we’re talking about here might operate in some way throughout the process of thinking and acting. The experience of will may accrue prior to action from the anticipation that we have an intention and that the act will come. After that, apparent mental causation arrives full-blown as we perceive both the intention and the ensuing act. We can experience the willful act of swinging a croquet mallet when our intention precedes the action, for instance, just as we might experience external causation on viewing, say, a mallet swinging through the air on a trajectory with a croquet ball, which it then hits and drives ahead. And later, on reflection, we might also be able to recall an experience of will. So the inference process that yields conscious will does its job throughout the process of actual action causation, first in anticipation, then in execution, and finally in reflection.