The Illusion of Conscious Will (51 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

6.

There is a natural tendency to assume that people remain conscious of the pretense when they fake. This idea that role adoption is conscious, or remains even partially conscious, however, is not usually defended by social cognitive theorists (e.g., Kirsch 1998). People are surely not conscious of faking, at least after the first little while, when they play the roles of everyday life. A lack of consciousness of the processes whereby one has achieved a mental state, however, suggests a kind of genuineness—a sense in which the state is an “altered state of consciousness”—and this is what many of the trance theorists would prefer to call hypnosis (e.g., Spiegel 1998). Much of the interchange between the “trance” and the “faking” theorists is nominally about other things yet actually hinges in a subtle way on this issue. There are hundreds of mental states we achieve every day in which, during the state, we are no longer conscious of having tried to or wanted to achieve that state (Wegner and Erber 1993). The argument between the “trance” and the “faking” theorists seems to result from different viewpoints: thinking about hypnosis with respect to

how it seems

(trance) or

how one got there

(faking).

So, where are we? At this point in the development of an explanation of hypnosis, none of these theories is winning. All seem to be losing ground. Trance theories have difficulty dealing with the social influence processes that give rise to hypnosis, and faking theories leave out the brain and body entirely, warts and all. The conflict between the trance theorists and the faking theorists has collapsed into mayhem, to the point that some are calling for a truce (Chaves 1997; Kirsch and Lynn 1995; Perry 1992; Spiegel 1998).

It should be clear from the evidence we have reviewed regarding hypnosis and other instances of the loss of conscious will that there is a vast middle ground now available for encampment. A theory that takes into account both the social forces impinging on the individual and the significant psychological changes that occur within the individual as a result of these forces must be the right way to go. Something along the lines of the self-induction theory of spirit possession, in which people’s pretendings and imaginings turn into reality for them, seems fitting. As with possession, some people seem to be able to fake themselves into a trance. Such a theory of “believed-in imaginings” has in fact been proposed in several quarters of the hypnosis debates (Perry 1992; Sarbin and Coe 1972; Sutcliffe 1961), and further progress in the study of hypnosis may depend on the development of a more complete theory along these lines.

The theory of apparent mental causation is not a complete theory of hypnosis, so we don’t need to worry about joining the fray. The idea that the experience of will is not an authentic indication of the force of will, however, can help to clear up some of the difficulties in the study of hypnotic involuntariness. Our analysis of the experience of conscious will suggests that we could make some headway toward understanding hypnosis by examining how people perceive the causation of behaviors they are asked, instructed, or pressured to perform.

Partitioning Apparent Mental Causation

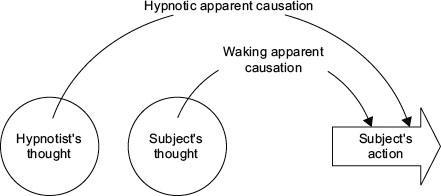

Hypnosis presents an action authorship problem to the hypnotic subject. This occurs because the actual causal situation in any case of social influence is more complicated than the causal situation in basic individual action. In the usual waking state, things are relatively simple. A person’s perception of apparent mental causation often tracks the actual relation between conscious thought and behavior (

fig. 8.7

). Conscious thoughts come to mind before the behavior and play a role in the mechanisms that produce the behavior. But, at the same time, the apparent causal relation between thought and behavior is perceived and gives rise to an experience of will. When everything is well-oiled and working normally, the person experiences will in a way that maps at least approximately onto the actual causal relation between conscious thought and behavior, and the person thus experiences a sense of voluntariness. The experience of will tracks the force of will.

Figure 8.7

Experience of will during waking state and hypnotic state. In waking, the subject perceives an apparent influence of own thought on own action that may reflect the actual influence. In hypnosis, the subject perceives an apparent influence of the hypnotist’s thought on own action, bypassing the influence of own thought and so reducing the experience of will.

In the case of hypnosis, the perception of apparent causation must now take into account two actual causal links: the hypnotist’s thought influencing the subject’s thought, and the subject’s thought influencing his or her own action. This is where the perception process takes a shortcut. Perhaps not immediately, but at some point in the process of hypnosis, the subject’s awareness of the role of his or her own thought in this sequence drops out. The hypnotist’s thought is perceived as having a direct causal influence on the subject’s action, and the experience of will thus declines. Feelings of involuntariness occur even though there remains an actual link between the subject’s thought and action. The subject’s thought may actually become more subtle at this time, perhaps even dropping from consciousness. But there must be mental processes involved in taking in the information from the hypnotist and transforming it into action. They may not have a prominent role in the subject’s consciousness, however, and so do not contribute to sensed will.

People in hypnosis may come to interpret their thoughts, even if they are conscious, as only part of a causal chain rather than as the immediate cause of their action. There is evidence of a general tendency to attribute greater causality to earlier rather than later events in a causal chain—a causal primacy effect (Johnson et al. 1989; Vinokur and Ajzen 1982). So, for instance, on judging the relative causal importance of the man who angered the dog who bit the child, we might tend under some conditions to hold the man more responsible than the dog. This should be particularly true if the man’s contribution itself increased the probability of the bite more than did the dog’s contribution (Spellman 1997). Moreover, this effect may gain influence with repetition of the sequence (Young 1995). The development of involuntariness in hypnosis may occur, then, through the learning of a causal interpretation for one’s action that leaves out any role for one’s own thoughts, conscious or not. Over time and repetition, the hypnotist’s suggestions are seen as the direct causes of one’s actions.

How might people stop noticing the causal role of their own thoughts? One possibility is suggested by Miller, Galanter, and Pribram (1960) in

Plans and the Structure of Behavior:

Most of our planned activity is represented subjectively as listening to ourselves talk. The hypnotized person is not really doing anything different, with this exception: the voice he listens to for his Plan is not his own, but the hypnotist’s. The subject gives up his inner speech to the hypnotist. . . . It is not sufficient to say merely that a hypnotized subject is listening to plans formulated for him by the hypnotist. Any person . . . listening to the same plans . . . would not feel the same compulsion to carry them out. . . . [The] waking person hears the suggested plans and then either incorporates them or rejects them in the planning he is doing for himself. But a hypnotized subject has stopped making plans for himself, and therefore there can be no question of coordination, no possible translation from the hypnotist’s version to his own. The hypnotist’s version of the plan is the only one he has, so he executes it. . . . How does a person stop making plans for himself? This is something each of us accomplishes every night of our lives when we fall asleep. (104-105)

These theorists suggest that the standard procedure for sleep induction, like that for hypnosis, involves turning down the lights, avoiding excessive stimulation, getting relaxed, and either closing the eyes or focusing on something boring. They propose that unless insomnia sets in, this shuts down the person’s plan generator. One stops talking to oneself, and action is generally halted. In hypnosis, the person doesn’t fall asleep because another person’s voice takes over the plan generation function and keeps the body moving.

This approach suggests that people may interpret their thoughts about their behavior as causal or not. They may see some thoughts about upcoming actions as intents or plans, whereas they see other thoughts about those actions as noncausal—premonitions, perhaps, or imaginings, or even echoes of what has come before or of what they are hearing. When the thoughts occurring before action are no longer viewed as candidates for causal status, the experience of will is likely to recede. In the case of hypnosis, then, the exclusivity principle may be operating to yield reduced feelings of will. The presence of the hypnotist as a plausible cause of one’s behavior reduces the degree to which one’s own thoughts are interpreted as candidate causes, and so reduces the sense of conscious will.

Thoughts that are consistent with an action in hypnosis might not be appreciated as causal if they happen to be attributed to the hypnotist. A lack of exclusivity could preempt this inference, as might often happen whenever a person is given an instruction and follows it. Someone says, “Please wipe your feet at the door,” and you do so. Although there could be a sense that the act is voluntary, there might also be the immediate realization that the thought of the act was caused by your asker’s prior thoughts. In essence, both the self’s thought and the other’s thought are consistent with the self’s action in this case, and the inference of which thought is causal then is determined by other variables. There may be a general inclination to think that self is causal, or an inclination to think that other is causal, as determined by any number of clues from the context of the interaction.

The ambiguities of causation inherent in instructed or suggested actions open the judgment of apparent mental causation to general expectations. A sense of involuntariness may often emerge as the result of a prior expectation that one ought not to be willful in hypnosis. In research by Gorassini (1999), for example, people were asked what they were planning to do in response to hypnotically suggested behaviors. Their plans fell into four groups we might name as follows:

wait and see

(planned to wait for the suggested behavior to occur on its own),

wait and imagine

(planned to wait for the suggested behavior and imagine it happening),

intend to act and feel

(planned to go ahead and do the act and try to generate a feeling of involuntariness), and

cold acting

(planned to go ahead and do the act but not try to experience involuntariness). Gorassini described the third group here, those who intended to do the act and try to get the feeling, as the “self-deception plan” group. These people planned to fake the behavior and also try to fake the feeling.

The relation between these plans and actual hypnotic behavior was assessed in a variety of studies, and it was generally found that plans to wait didn’t produce much.

Wait and see

yielded few hypnotic responses, and

wait and imagine

was a bit better but still did little.

Cold acting

produced hypnotic responses but little experience of involuntariness. The people who were self-deceptive, in that their plan was

intend to act and feel,

produced both the most frequent suggested behavior and the strongest reports of involuntariness. Apparently, those people who followed the suggestions and actively tried to experience the feeling of involuntariness were the ones who succeeded in producing a full-blown hypnotic experience.

Now, in normal waking action, the thought, act, and feeling arise in sequence. We think of what we will do, we do it, and the feeling of conscious will arises during the action. Gorassini’s findings suggest that in hypnosis, the feeling of involuntariness may be substituted in advance as a counterfeit for the usual feeling of voluntariness. A distinct lack of will is something we’re looking for and trying to find even as we are aware of our thoughts and our behaviors. Such readiness to perceive involuntariness may thus short-circuit our usual interpretive processes. We no longer notice the fact that our thoughts do appear prior to the action and are consistent with the action because the overall set to experience the action as unwilled—because of the clear absence of exclusivity (the hypnotist, after all, is an outside cause)—overwhelms the interpretive weight we might usually assign to these factors. Instead, the behavior is perceived as emanating from the hypnotist’s suggestions and, for our part, as happening involuntarily.

Control through Involuntariness

The analysis of apparent mental causation can account for the experience of involuntariness. But how do we account for hypnotic behavior? The theory of apparent mental causation is not clear in its implications in this regard, which is why it is not a complete theory of hypnosis. It is not really necessary to have a special theory to explain the high degree of social influence that occurs in hypnosis. As we’ve seen, this may be due entirely to factors having little to do with hypnosis per se and more to do with the power of social influence itself. However, the unusual abilities of hypnotized people do need a theory. They do not appear, however, to arise from variations in experienced voluntariness, and thus far these variations are all we’ve been able to begin to explain. How would involuntariness prompt the enhanced levels of control we have observed over pain, thought, memory, and the like?