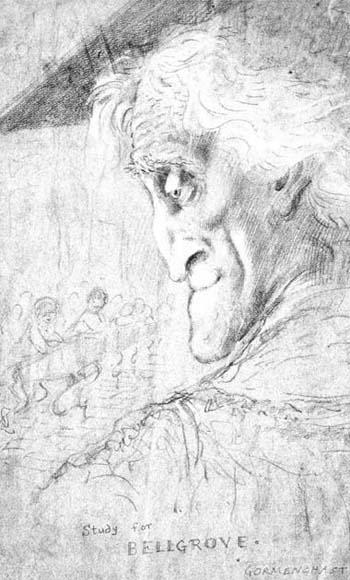

The Illustrated Gormenghast Trilogy (86 page)

Read The Illustrated Gormenghast Trilogy Online

Authors: Mervyn Peake

‘Must I

what

? Explain yourself, dear boy. If there’s anything I abominate it’s sentences of two words. You talk like a fall of crockery, dear boy.’

‘You’re a damned old pedant, Bellgrove, and much overdue for burial,’ said Perch-Prism, ‘and as quick off the mark as a pregnant turtle. For pity’s sake stop playing with your teeth!’

Opus Fluke in his battered chair, dropped his eyes and, by parting his long leather-lipped mouth in a slight upward curve, might have been supposed to be registering a certain sardonic amusement had not a formidable volume of smoke arisen from his lungs and lifted itself out of his mouth and into the air in the shape of a snow-white elm.

Bellgrove turned his back to the mirror and lost sight of himself and his troublesome teeth.

‘Perch-Prism,’ he said, ‘you’re an insufferable upstart. What the hell have my teeth got to do with you? Be good enough to leave them to me, sir.’

‘Gladly,’ said Perch-Prism.

‘I happen to be in pain, my dear fellow.’ There was something weaker in Bellgrove’s tone.

‘You’re a hoarder,’ said Perch-Prism. ‘You cling to bygone things. They don’t suit you, anyway. Get them extracted.’

Bellgrove rose into the ponderous prophet category once more. ‘Never!’ he cried, but ruined the majesty of his utterance by clasping at his jaw and moaning pathetically.

‘I’ve no sympathy at all,’ said Perch-Prism, swinging his legs. ‘You’re a stupid old man, and if you were in my class I would cane you twice a day until you had conquered (one) your crass neglect, (two) your morbid grasp upon putrefaction. I have no sympathy with you.’

This time as Opus Fluke threw out his acrid cloud there was an unmistakable grin.

‘Poor old bloody Bellgrove,’ he said. ‘Poor old Fangs!’ And then he began to laugh in a peculiar way of his own which was both violent and soundless. His heavy reclining body, draped in its black gown, heaved to and fro. His knees drew themselves up to his chin. His arms dangled over the sides of the chair and were helpless. His head rolled from side to side. It was as though he were in the last stages of strychnine poisoning. But no sound came, nor did his mouth even open. Gradually the spasm grew weaker, and when the natural sand colour of his face had returned (for his corked-up laughter had turned it dark red) he began his smoking again in earnest.

Bellgrove took a dignified and ponderous step into the centre of the room.

‘So I am “Bloody Bellgrove” to you, am I, Mr Fluke? That is what you think of me, is it? That is how your crude thoughts run. Aha! … aha! …’ (His attempt to sound as though he were musing philosophically upon Fluke’s character was a pathetic failure. He shook his venerable head.) ‘What a coarse type you are, my friend. You are like an animal – or even a vegetable. Perhaps you have forgotten that as long as fifteen years ago I was considered for Headship. Yes, Mr Fluke, “

considered

”. It was then, I believe, that the tragic mistake was made of your appointment to the staff. H’m … Since then you have been a disgrace, sir – a disgrace for fifteen years – a disgrace to our calling. As for me, unworthy as I am, yet I would have you know that I have more experience behind me than I would care to mention. You’re a slacker, sir, a damned slacker! And by your lack of respect for an old scholar you only …’

But a fresh twinge of pain caused Bellgrove to grab at his jaw.

‘Oh, my

teeth

!’ he moaned.

During this harangue Mr Opus Fluke’s mind had wandered. Had he been asked he would have been unable to repeat a single word of what had been addressed to him.

But Perch-Prism’s voice cut a path through the thick of his reverie.

‘My dear Fluke,’ it said, ‘did you, or didn’t you, on one of those rare occasions when you saw fit to put in an appearance in a classroom – on this occasion with the gamma Fifth, I believe – refer to me as a “bladder-headed cock”? It has come to my hearing that you referred to me as exactly that. Do tell me: it sounds so like you.’

Opus Fluke stroked his long, bulging chin with his hand.

‘Probably,’ he said at last, ‘but I wouldn’t know. I never listen.’ The extraordinary paroxysm began again – the heaving, rolling, helpless, noiseless body-laughter.

‘A convenient memory,’ said Perch-Prism, with a trace of irritability in his clipped, incisive voice. ‘But what’s that?’

He had heard something in the corridor outside. It was like the high, thin, mewing note of a gull. Opus Fluke raised himself on one elbow. The high-pitched noise grew louder. All at once the door was flung open from without and there before them, framed in the doorway, was the Headmaster.

If ever there was a primogenital figure-head or cipher, that archetype had been resurrected in the shape of Deadyawn. He was pure symbol. By comparison, even Mr Fluke was a busy man. It was thought that he had genius, if only because he had been able to delegate his duties in so intricate a way that there was never any need for him to do anything at all. His signature, which was necessary from time to time at the end of long notices which no one read, was always faked, and even the ingenious system of delegation whereon his greatness rested was itself worked out by another.

Entering the room immediately behind the Head a tiny freckled man was seen to be propelling Deadyawn forward in a high rickety chair, with wheels attached to its legs. This piece of furniture, which had rather the proportions of an infant’s high chair, and was similarly fitted with a tray above which Deadyawn’s head could partially be seen, gave fair warning to the scholars and staff of its approach, being in sore need of lubrication. Its wheels screamed.

Deadyawn and the freckled man formed a compelling contrast. There was no reason why they should

both

be human beings. There seemed no common denominator. It was true that they had two legs each, two eyes each, one mouth apiece, and so on, but this did not seem to argue any similarity of

kind

, or if it did only in the way that giraffes and stoats are classified for convenience sake under the commodious head of ‘fauna’.

Wrapped up like an untidy parcel in a gun-grey gown emblazoned with the signs of the zodiac in two shades of green, none of which signs could be seen very clearly for reason of the folds and creases, save for Cancer the crab on his left shoulder, was Deadyawn himself, and all but asleep. His feet were tucked beneath him. In his lap was a hot-water bottle.

His face wore the resigned expression of one who knew that the only difference between one day and the next lies in the pages of a calendar.

His hands rested limply on the tray in front of him at the height of his chin. As he entered the room he opened one eye and gazed absently into the smoke. He did not hurry his vision and was quite content when, after several minutes, he made out the three indistinct shapes below him. Those three shapes – Opus Fluke, Perch-Prism and Bellgrove – were standing in a line, Opus Fluke having fought himself free of his cradle as though struggling against suction. The three gazed up at Deadyawn in his chair.

His face was as soft and round as a dumpling. There seemed to be no structure in it: no indication of a skull beneath the skin.

This unpleasant effect might have argued an equally unpleasant temperament. Luckily this was not so. But it exemplified a parallel bonelessness of outlook. There was no fibre to be found in him, and yet no weakness as such; only a negation of character. For his flaccidity was not a positive thing, unless jelly-fish are consciously indolent.

This extreme air of abstraction, of empty and bland removedness, was almost terrifying. It was that kind of unconcern that humbled the ardent, the passionate of nature, and made them wonder why they were expending so much energy of body and spirit when every day but led them to the worms. Deadyawn, by temperament or lack of it, achieved unwittingly what wise men crave: equipoise. In his case an equipoise between two poles which did not exist: but nevertheless there he was, balanced on an imaginary fulcrum.

The freckled man had rolled the high chair to the centre of the room. His skin stretched so tightly over his small bony and rather insect-like face that the freckles were twice the size they would normally have been. He was minute, and as he peered perkily from behind the legs of the high chair, his carrot-coloured hair shone with hair-oil. It was brushed flat across the top of his little bony insect-head. On all sides the walls of horsehide rose into the smoke and smelt perceptibly. A few drawing-pins glimmered against the murky brown leather.

Deadyawn dropped one of his arms over the side of the high chair and wriggled a languid forefinger. ‘The Fly’ (as the freckled midget was called) pulled a piece of paper out of his pocket, but instead of passing it up to the Headmaster he climbed, with extraordinary agility, up a dozen rungs of the chair and cried into Deadyawn’s ear: ‘Not yet! not yet! Only three of them here!’

‘What’s that?’ said Deadyawn, in a voice of emptiness.

‘Only three of them here!’

‘Which ones,’ said Deadyawn, after a long silence.

‘Bellgrove, Perch-Prism and Fluke,’ said The Fly in his penetrating, fly-like voice. He winked at the three gentlemen through the smoke.

‘Won’t

they

do?’ murmured Deadyawn, his eyes shut. ‘They’re on my staff, aren’t … they …?’

‘Very much so,’ said The Fly, ‘very much so. But your Edict, sir, is addressed to the whole staff.’

‘I’ve forgotten what it’s all about. Remind … me …’

‘It’s all written down,’ said The Fly. ‘I have it here, sir. All you have to do is to read it, sir.’ And again the small red-headed man honoured the three masters with a particularly intimate wink. There was something lewd in the way the wax-coloured petal of his eyelid dropped suggestively over his bright eye and lifted itself again without a flutter.

‘You can give it to Bellgrove. He will read it when the time comes,’ said Deadyawn, lifting his hanging hand on to the tray before him and languidly stroking the hot-water bottle … ‘Find out what’s keeping them.’

The Fly pattered down the rungs of the chair and emerged from its shadow. He crossed the room with quick, impudent steps, his head and rump well back. But before he reached the door it had opened and two Professors entered – one of them, Flannelcat, with his arms full of exercise-books and his mouth full of seedcake, and his companion, Shred, with nothing in his arms, but with his head full of theories about everyone’s subconscious except his own. He had a friend, by name Shrivell, due to arrive at any moment, who, in contrast to Shred, was stiff with theories about his own subconscious and no one else’s.

Flannelcat took his work seriously and was always worried. He had a poor time from the boys and a poor time from his colleagues. A high proportion of the work he did was never noticed, but do it he must. He had a sense of duty that was rapidly turning him into a sick man. The pitiful expression of reproach which never left his face testified to his zeal. He was always too late to find a vacant chair in the Common-room, and always too early to find his class assembled. He was continually finding the arms of his gown tied into knots when he was in a hurry, and that pieces of soap were substituted for his cheese at the masters’ table. He had no idea who did these things, nor any idea how they could be circumvented. Today, as he entered the Common-room, with his arms full of books and the seedcake in his mouth, he was in as much of a fluster as usual. His state of mind was not improved by finding the Headmaster looming above him like Jove among the clouds. In his confusion the seedcake got into his windpipe, the concertina of school books in his arms began to slip and, with a loud crash, cascaded to the floor. In the silence that followed there was a moan of pain, but it was only Bellgrove with his hands at his jaw. His noble head was rolling from side to side.

Shred ambled forward from the door and, after bowing slightly in Deadyawn’s direction, he buttonholed Bellgrove.

‘In pain, my dear Bellgrove? In pain?’ he inquired, but in a hard, irritating, inquisitive voice – with as much sympathy in it as might be found in a vampire’s breast.

Bellgrove bridled up his lordly head, but did not deign to reply.

‘Let us take it that you

are

in pain,’ continued Shred. ‘Let us work on that hypothesis as a basis: that Bellgrove, a man of somewhere between sixty and eighty, is in pain. Or rather, that he

thinks

he is. One must be exact. As a man of science, I insist on exactitude. Well, then, what next? Why, to take into account that Bellgrove, supposedly in pain, also thinks that the pain has something to do with his teeth. This is absurd, of course, but must, I say, be taken into account. For what reason? Because they are symbolic. Everything is symbolic. There is no such thing as a “thing”

per se

. It is only a symbol of something else that is itself, and so on. To my way of thinking his teeth, though apparently rotten, are merely the symbol of a diseased mind.’