The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (19 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

The diplomatic despatch was in this respect an unintended by-product of this evolutionary process. ‘The business of an ambassador,’ as Bernard du Rosier emphasised repeatedly in his influential ‘Short Treatise’ (1436) on the

office of diplomacy, ‘is peace.’

3

‘The speedy completion of an ambassador's mission is in the interest of all.’ Nowhere was it envisaged that these illustrious plenipotentiaries should become informed observers of the host state. But as time went by, and the web of negotiation between contesting powers became more intricate, the need for informed assessment of the mood, strength and true intentions of potential allies became ever more acute. Ambassadors were instructed to write home on a regular basis. The art of diplomacy had spawned a whole new medium: political commentary. This was the first real sustained attempt to add commentary and analysis to the raw data of news.

5.1 A diplomatic mission asks for the hand of the king's daughter in marriage.

About the earliest generation of diplomatic despatches we are not well informed. Though in other respects precocious exponents of bureaucracy, the Italian states did not make provision for the systematic filing of incoming ambassadorial reports. The earliest examples have only survived because they made their way into family archives: the papers and despatches accumulated by an envoy abroad remained, just like ministerial papers, their own personal property, to be retained or disposed of as they thought best.

4

Venice legislated to ensure that all public papers in the possession of returning diplomats were surrendered to the state, but to little avail.

5

It was only in the 1490s that Venice began to assemble an archive. But what despatches they are: over the course of two centuries Italian ambassadors abroad offer a stream of shrewd and well-informed observations on the politics, customs and personalities of their hosts. Their reports range widely, from the immediate issues of the day, through gossip, strange occurrences, to more anthropological observations about the differences of national character, dress and behaviour. Tempered in the harsh schools of Italian politics, closely connected to the business elites from which they were sometimes drawn, pragmatic and thoughtful, Italian ambassadors were ideally suited to this new craft.

Diplomatic despatches were not, of course, public documents. They were intended only for a limited circle in the innermost councils of the state: this was news and analysis for a privileged elite. But some news did begin to leak out, through indiscretion or the vanity of the envoy. A semi-licensed form of publicity developed with the tradition of the

Relazione

, the final reflective despatch presented to the Venetian Senate on the conclusion of an embassy. The purpose of a

Relazione

was quite different from that of the regular despatch. Rather than reporting on the hubbub of everyday events, the ambassador now took stock: he offered his view on the character of the ruler and his principal advisors, the strengths and weaknesses of the state, the attitudes and sentiments of the people.

6

These reflections were presented orally, by men who relished the opportunity for a display of erudition.

Relazioni

were eagerly anticipated, not least for the calculated indiscretion. Who, of those present,

would not have marvelled at the impudence of ambassador Zaccaria Contarini's frank description in 1492 of Charles VIII of France:

The Majesty of the King of France is twenty-two years of age, small and badly formed in his person, ugly of face, with eyes great and white and much more apt to see too little than enough, an aquiline nose, much larger and fatter than it ought to be, also fat lips, which he continually holds open, and he has some spasmodic movements of hand which appear very ugly, and he is slow in speech. According to my opinion, which could be quite wrong, I hold certainly that he is not worth very much either in body or in natural capacity.

7

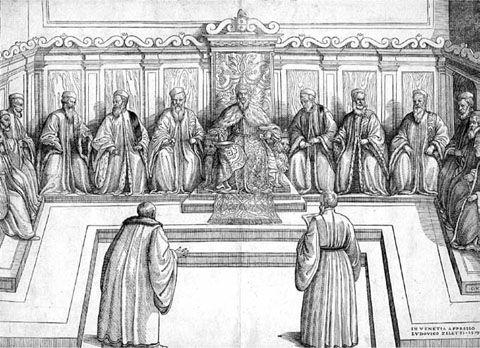

5.2 The reading of a despatch before the Doge of Venice and other members of the Signoria.

This was not kind; all the more so as this candid and rude assessment was very likely to filter back to France, souring relations and complicating the life of Contarini's unlucky successor as ambassador there. But among contemporaries such despatches were much admired. The anonymous French author of

Traité du gouvernement de Venise

, composed about 1500, noted with approval that newly appointed ambassadors would seek out in the archives the

Relazioni

of their predecessors, in order to begin their missions well briefed.

8

These documents circulated widely among the senators, and many Venetian families kept copies of those which they believed brought them honour. With the passage of time copies were made and circulated outside the circles of those strictly entitled to see them; some copies changed hands for money. Towards the end of the sixteenth century the Venetian Senate finally acknowledged the public value of

Relazioni

and allowed a small number of them to appear in print. Presumably none of those chosen contained anything as wounding as Contarini's dissection of the young French king a century before.

5.3 Charles VIII of France.

Lying Abroad

In the development of international diplomacy a crucial figure was the shrewd and far-sighted Ferdinand, King of Aragon (r. 1479–1516). As ruler of Spain's Mediterranean kingdom he had a close interest in Italy at a time when French ambitions in the peninsula were transforming its politics. As co-ruler of Castile, through his wife Isabella, Ferdinand was the master of Europe's incipient superpower, Spain. His great strategic goal was to challenge the hegemony of France; his principal instrument, alliance backed by traditional dynastic marriages. In the pursuit of these goals Ferdinand established a web of permanent embassies: his was the first of Europe's nation states to do so. He

even attempted to plant an embassy in France, largely to collect military intelligence. Such a legation, to a hostile power, would again have been a first, but Charles VIII was no fool and Ferdinand's envoy was soon sent packing.

9

Ferdinand was not an easy man to please. The king sometimes neglected to write to his ambassadors for long periods, and often kept them in ignorance of his plans. His reciprocal demands for regular information were made without concern for the logistical obstacles. His long-suffering London envoy, Dr de Puebla, calculated that to send news to Ferdinand daily, as the king had requested, would require a relay of sixty couriers; in fact de Puebla had two, and could not afford to pay those. Ferdinand was also careless with paperwork, and prone to leave unsorted chests of papers in remote castles. But like Emperor Maximilian, his irrepressible contemporary, Ferdinand was an innovator. He left his ambassadors in place long enough for them to become real experts: nine years was the norm, and de Puebla was in London for most of the last twenty years of his life. As a result, Ferdinand bequeathed to his grandson Charles V a Spanish diplomatic corps that remained an established fact of European politics for the rest of the century.

A case study in suave and effective diplomatic service is provided by Eustace Chapuys, long-term ambassador for the Emperor Charles at the court of King Henry VIII.

10

Chapuys arrived in September 1529 in unpromising circumstances. Henry VIII had by now made unmistakably clear his determination to proceed with divorcing Katherine of Aragon. The queen, previously a valuable source of informed advice for the Spanish envoys, was no longer available for consultation; and the ambassador could scarcely in all conscience conceal his master's appalled opposition to Henry's policies. But over the course of sixteen years Chapuys gradually created a dense and subtle network of information to pepper the shrewd and well-sourced reports that have been such a treasure trove for historians. His first step was to take into his service several members of Katherine's household, including her gentleman usher, Juan de Montoya, who now became his private secretary. Young men of breeding, who could circulate unobtrusively at court, were recruited from France and Flanders. Although Chapuys did not speak English himself, he insisted that these young men should learn the language; the taciturn valet who accompanied him everywhere (Chapuys suffered from gout) was also a talented linguist. Through these agents Chapuys heard much of value that should not have been said in his presence. He was also at pains to lavish care and hospitality on the international merchant community, the source of a great deal of valuable information about currency movements, and on the incipient Lutheran movement (Chapuys had his friends among the German merchants too). Some information was paid for. It was a major coup to turn the French ambassador's principal secretary, who for eighteen months made available to

Chapuys Marillac's private correspondence, and Chapuys also received regular reports from one of Anne Boleyn's maids. But most of what he reported was freely given, from the merchants ‘who visit me daily’: the gossip of informed but often lonely men far from home, exchanged for hospitality and good fellowship.

A Spaniard in Rome

In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries Rome had been the inadvertent laboratory of the new diplomacy. A common desire to exploit the resources of the Catholic Church made it necessary for Europe's rulers to send frequent emissaries to Rome requesting the confirmation of nominees in ecclesiastical office and other favours. Forced to linger by the slow pace of papal business, they became, in effect, ambassadors. Even in the sixteenth century Rome lost none of its importance as a centre of business, politics and news. Its centrality in the political calculations of the Spanish Habsburgs is indicated by the fact that the Roman ambassador was always paid the largest salary (though this, in common with all ambassadorial remuneration, never covered expenses).

11

Although the Habsburgs had largely succeeded in establishing supremacy in the Italian Peninsula in the sixteenth century, vanquishing French competition, their ambassadors were ever vigilant. Their reports suggest anxiety more than confidence, and an overwhelming sense of the volatility of Italian politics. The case was well put by Miguel Mai, imperial ambassador to Rome, in a despatch to Charles V in 1530:

As Rome is the vortex for all the world's affairs, and the Italians catch fire at the least spark, those who are partisan and even more those who have been ruined [by recent events] are stirring up trouble here, because they always want novelties.

12

Note that this was written only months after the great triumph of Charles V's coronation at Bologna, when imperial power was at its apparent height. Spanish ambassadors returned again and again to the Italian thirst for novelty (

novedades

) that made them such fickle allies, and here they made no distinction between Rome, Venice and Florence. Spain, of course, wanted the opposite, quiescent allies who appreciated the virtues of Spanish hegemony. In this they were constantly disappointed.