The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (36 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Verhoeven was learning his trade as he went along, and keeping up a hectic pace. Happily, as his paper was an official venture Verhoeven could rely on a great deal of help. The well-known Catholic polemicist Richard Verstegen wrote for him often; the leading Catholic clerics of Antwerp were supportive.

27

Each issue carried the imprimatur of the local censor. For ten years Verhoeven kept up a relentless schedule of publication. There were a remarkable 192 numbered issues of the

Nieuwe Tijdinghen

in 1621, and 182 in 1622. Between 1623 and 1627 only once did the number fall below 140. These totals also do not take into account that demand for the paper often required Verhoeven to reprint certain issues: careful examination of individual numbers reveals small differences suggesting that the printer was frequently required to run off extra copies to meet demand.

28

While the imperial cause prospered, so did Verhoeven. Yet in 1629 he suspended his pamphlet news serial, resuming a few months later with a more

conventional weekly newspaper. What had precipitated this change is not certain. Perhaps demand was falling as the tide of war began to turn against the Catholic forces; and the Antwerp authorities were becoming tetchy. In February of that year the Council of Brabant instructed Verhoeven to desist from his ‘daily’ publication ‘of various gazettes or news reports most incorrect and without prior proper visitation’, a charge as unfair as it was inaccurate, given Verhoeven's almost slavish adherence to the Catholic and imperial cause.

29

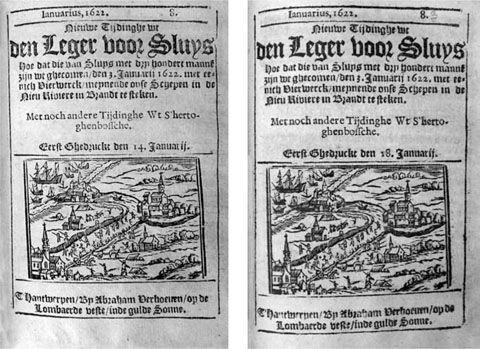

9.3 V erhoeven's

New Tidings

. The popularity of his serial news pamphlets was such that Verhoeven was frequently, as here, forced to reprint individual issues.

Perhaps Verhoeven himself was worn down by the relentless schedule of publication. Most early modern serials that relied on a single charismatic voice for success were of short duration, and by lasting a decade Verhoeven had outlived most such enterprises. It is certainly the case that the issues of the

Nieuwe Tijdinghen

were beginning to look a little tired. The woodcuts that Verhoeven had prepared for the first issues had now been used and reused many times over. And Verhoeven was running short of money. In 1623 he had written to the Antwerp city council to remind them that payment for their block order of 24 copies was seriously in arrears: he asked for 145 gulden to

clear the debt, but received only 50. In truth, Verhoeven never seems to have been a particularly effective business manager. In 1625 he came into property from his parents, but in the same year his wife fell ill, and her prolonged period of invalidity, before she died in 1632, was a further drain on his resources.

So in 1629 Verhoeven announced the end of his

Nieuwe Tijdinghen

. A month or so later he launched a weekly news pamphlet, the

Wekelijcke Tijdinghe

. This was the response of a scared or defeated man. After the innovation, variety and energy of the

Nieuwe Tijdinghen

, this new enterprise was merely a pallid imitation of the German and Dutch papers, a single sheet folded once to make four pages with the same sequence of sober news reports. But if Verhoeven thought this reversion to the norm would rescue his fortunes, he was sadly misguided. The

Wekelijcke Tijdinghe

lasted less than two years, its successor the two-page

Courante

only another two. In 1634 Verhoeven sold his business, and the paper, to his second son Isaac. The last years of his life were miserable indeed: forced to live in rented accommodation, eking out a living as a day labourer in his son's workshop.

Verhoeven's vision, of a serial publication that combined the business model of a newspaper with the familiar excitement and style of news pamphlets, was by far the most interesting experiment of this transitional age of news reporting. But it was not widely imitated. It would be two centuries before the mixture of news, comment and blatant partisanship that characterised Verhoeven's work would make the leap from occasional pamphlets to the newspapers. His tabloid values proved to be ahead of their time.

A Staple of News

By the last decades of the sixteenth century English readers had developed a strong taste for news. As the country was drawn ever deeper into continental warfare after the Armada campaign, London printers found a ready market for translations of French and Dutch accounts of the wars.

30

In the first years of the new century policymakers and gentry customers could also avail themselves of the first regular manuscript news services, edited by London newsmen from continental sources.

31

The growing public interest in current affairs was not viewed with any great warmth by the recently imported Scottish king, James VI and I. The latter half of his reign, in particular, was a difficult time for English foreign policy. The gathering storm in Germany inspired widespread public enthusiasm for the Protestant cause. The cautious king, unwilling to be stampeded into military action, had no wish that this enthusiasm should be fuelled by incessant printed reports of the unfolding situation. A proclamation of 1620 warned pointedly against ‘excess of lavish

and licentious speech in matters of state’. Duly warned, the generally docile and submissive London printers drastically reduced their production of news pamphlets dealing with continental affairs.

It is therefore no surprise that the first serial news publication in English was published not in London but in Amsterdam. In December 1620 the enterprising Pieter van den Keere published the

Courant out of Italy, Germany etc

. This was a straightforward translation of the Dutch edition, published in the same single-sheet format.

32

It was sufficiently successful for van den Keere to maintain publication for the best part of a year. Success brought imitation: by 1621 several of these single-sheet ‘corantos’ were in circulation. The most successful, though prudently attributed to the Amsterdam firm of Broer Jansz, may actually have been printed in London, and from September 1621 the London publisher Nathaniel Butter was openly advertising his responsibility for what was in effect a continuation of van den Keere's series.

33

Several other London printers also re-entered the market with unnumbered pamphlet news-books.

34

Rather than tolerate an unregulated free-for-all, the English authorities resorted to their preferred means of control: establishing a monopoly. This was awarded to Butter and Nicolas Bourne, who were now permitted to publish a weekly news-book provided it was submitted for prior inspection. The publishers would not be permitted to publish any domestic news or comment on English affairs. What was intended was a dry and fairly literal translation of the reports inherited from the continental newspapers.

While they accepted these conditions in order to kill off competition, Butter and Bourne soon demonstrated that they would bring to their task a keen commercial spirit. Butter was an old hand with printed news: news pamphlets, many of them with tales of sensational domestic murders, had made up a large part of the output of the print shop he had inherited from his father. Immediately Butter and Bourne converted their news-book back from the single sheet of the Amsterdam translations to the familiar pamphlet form.

35

Rather than follow the practice of the German newspapers, where the news followed immediately after the heading on the title-page, the English editors chose to imitate Verhoeven's Antwerp style (or that of their own earlier news pamphlets) where the title-page was occupied with a description of the contents.

36

Deprived of the opportunity to decorate their pamphlets with an expressive woodcut (this was not something that could easily have been furnished in London), Butter and Bourne instead allowed their title-page description of contents to stray down the whole page. Since this militated against a standard title, only the provision of a date and numbering reminded the reader that these were part of a serial.

Nor were Butter and Bourne prepared to replicate slavishly the contents of the continental news-books. At some point around 1622 they engaged the services of an editor, Captain Thomas Gainsford. Gainsford was the classic English adventurer. Driven by debt into military service, he had travelled extensively on the continent, ending with a period in the service of Maurice of Nassau. Like Nathanial Butter he was a passionate advocate of the Protestant cause. Returning finally to England, Gainsford embarked on a somewhat unlikely literary career, specialising in works of popular history. Butter, the publisher of at least one of these volumes, clearly thought of him as the man to add spice and zest to the rather lifeless reports inherited from the continental news-books.

37

In this Gainsford succeeded magnificently. The reports of troop movements and diplomatic manoeuvres were knitted together into a coherent narrative. Sometimes Gainsford would address the ‘Gentle reader’ directly, assuring him of the veracity of the reports and defending himself against any taint of partiality. These murmurings must have stung, for Gainsford was eventually moved to a spirited defence:

Gentle readers, how comes it then to pass that nothing can please you? If we afford you plain stuff, you complain … it is nonsense; if we add some [embellishment], then you are curious to examine the method and coherence, and are forward in saying the sentences are not well adapted.

38

Nor could Gainsford concoct news if none were to be had. Readers must not be greedy, not ‘look for fighting every day, nor taking of towns; but as they happen you shall know’

39

.

Butter and Bourne faced one problem that did not impact on the continental news men: the English Channel. If the wind was adverse, or the sea shrouded in fog, the news reports could not get through, and the English news-books had nothing to report. So the English news-books do not observe the strict periodicity of their continental peers: a weekly issue was the clear intention, but the London paper had no regular day of publication. Even so it seems to have been widely read in London and distributed to the country by the regular London carrier services. Gentlemen readers took to enclosing corantos in their correspondence with friends.

40

Even the purveyors of the subscription manuscript news services recommended that their moneyed clients also read the printed sheets. John Pory put it rather loftily in a letter to John Scudamore: ‘The reason [

sic

] why I would have your lordship read all corantos are, first, because it is a shame for a man of quality to be ignorant of that which the vulgar know.’

41

It is interesting that Pory did not regard the new printed medium as any sort of threat to his superior bespoke service; as on the continent, the two subsisted together.

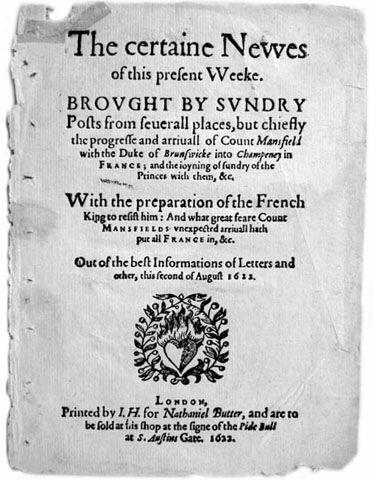

9.4 Butter's news serial. Only later in this year did Butter begin to number the series.

Thomas Gainsford died in 1624 and was not replaced. Without him the news-books struggled to maintain their appeal. The printers adopted the non de plume

Mercurius Britannicus

, and gave their news-books a title that most usually began

The continuation of our weekly news

; but by this date the news for a predominantly Protestant audience was unremittingly bad, and this may have damaged sales. In 1625 Butter made a memorable appearance in Ben Jonson's

A Staple of News

, a brilliant satire on the craze for current affairs. Jonson's darts hit the mark, but he was, if anything, unlucky with his date. Not only was the craze declining, the play also pre-dated by a couple of years the most remarkable episode of the early history of English newspapers: an attempt to corral the newspaper trade as a propaganda vehicle for the Duke of Buckingham's assault on La Rochelle.