The Irresistible Henry House (37 page)

Read The Irresistible Henry House Online

Authors: Lisa Grunwald

Tags: #Women teachers, #Home economics, #Attachment behavior, #Orphans, #Family Life, #Fiction, #Psychological, #Fiction - General, #American Contemporary Fiction - Individual Authors +, #General

A bus drove by. A dog pulled on its leash. A teenage couple perched on the back of a bench laughed and shared a small brass pipe.

“Whose is she?” he asked Mary Jane.

“She’s mine, doofus.”

“You know what I mean. Who’s her father?”

Mary Jane looked surprised. “It’s George, of course. Who do you think?”

“And he flew the coop. Useless creep.”

“He didn’t

fly the coop,

Henry.”

He grabbed Mary Jane’s left hand and held it up, her pale, unadorned fingers fanned out against the background of the flowering branches.

“Where’s the wedding ring?” Henry asked.

She laughed. “You’re so conventional, Henry.”

“Please.”

“Did it ever occur to you that

I

didn’t want to marry him? Maybe I like him just coming and going.”

“I wouldn’t go,” Henry said huskily, and Mary Jane burst out laughing, a little too forcefully, as if her laughter would be able to keep his evident purpose in check.

“I mean it,” he told her.

She laughed again. “Are you out of your tiny mind?”

“You find this laughable?” Henry asked.

She looked at her wristwatch.

“Don’t let me keep you,” he said acidly.

“The babysitter’s only staying till six.”

“I’M GLAD YOU LEFT THAT PEACE GIRL, anyway,” Mary Jane said as they walked back to her house.

“You only met her for two minutes,” Henry said.

“True. But you’ve never met George, and you’ve already called him a worthless creep.”

“Actually, I said a

useless

creep.”

“Same difference.”

“Where is he, anyway?” Henry asked.

She turned the key in the front door, ignoring his question completely. Within seconds she was assaulted by the toddler at her knees.

The little girl was wearing red Keds, blue jeans, and a red T-shirt. On another child, the outfit would have looked boyish, but the delicacy of her features and her winsome eyes made her utterly little-girlish.

“Haley, say hello,” Mary Jane said.

Henry bent down and looked into both her eyes—her two undamaged, perfect blue eyes—and realized that this was what looking at Mary Jane must have been like, years before.

“Hi, Haley,” he said.

He started to extend his hand in greeting, but Haley instead used one hand to spread two fingers on her other into a tiny, perfect peace sign. Henry followed suit, then pressed his two fingers onto hers.

“Hi,” she said.

“Hi.”

Mary Jane asked the babysitter to stay while she started dinner.

THE KITCHEN WAS A MESS. Toy pots and pans vied for counter space with the real items, as did toy plates, cups, and one well-smudged wooden toaster.

“She’s beautiful,” Henry said.

Mary Jane tried to hide her smile by opening the refrigerator door.

“She looks exactly like you,” Henry said.

Mary Jane handed Henry four potatoes.

“See, I know that,” Henry said, “because I knew you when you were just a little older than she is now.”

“Potatoes,” Mary Jane directed, handing Henry a potato peeler.

“I’m serious, you know,” Henry said.

“I know.”

“We grew up together. Think of everything.”

“Just because we have a past doesn’t mean we have a future.”

“But it should,” Henry said.

He embraced her. It was as tender a moment as any he’d had with Annie, as passionate as any he’d had with Peace. He had a hand on either side of Mary Jane’s face, and he wanted her to feel completely encompassed, held and met and lifted up. He kissed her, watching till her one eye closed, and then he closed his own.

Then she took his right hand in hers and kissed the back of it, emphatically, three times.

“No,” she said, and then repeated it when she saw the expression on his face.

Henry looked at her, shaking his head. Mary Jane sent him to the living room.

“Not now, Henry,” she said, which he chose to interpret as meaning “maybe someday.”

“Go be with the other kids,” she told him, laughing.

“SIT?” HALEY ASKED HIM after the babysitter had left.

She was sitting at a low wooden play table.

“Okay,” Henry said and took his place at a small matching wooden chair.

“Uppy?” she asked him.

“You want me to pick you up?”

He did, with one arm, and she slid onto his lap.

A wooden box with a sliding top sat on the table before them. Proudly, if with difficulty, Haley slid the top of the box back to reveal a riot of crisscrossed colors and the warm, waxy, earthy smell of crayons.

There was a stack of paper beside the box. Henry took one sheet for himself and another for her.

“What color do you want?” he asked her.

“Green.”

He picked out a crayon for her. Spring Green.

She swung one leg freely against his, as if his leg was the leg of the chair.

For himself, he picked up Red. Just red. But as soon as he did, she took it from him, grinning. He laughed. “Okay,” he said. He took a purple crayon next. She did the same thing again. Soon she held a huge bouquet of crayons, all the colors she could keep in her small hand.

“May I keep this one, miss?” Henry asked her, holding up the crayon called Burnt Sienna. She giggled and nodded.

From the kitchen, he could hear Mary Jane humming, but he couldn’t make out the tune. Haley stayed on his lap, her entire face, her entire body, focused into one scrunched-up force of concentrated effort. She pressed her whole weight into the crayon, pushing it back and forth.

Henry stared down at the blank paper. Stared and stared as he tried to absorb the words Mary Jane had said to him, and the ones she hadn’t said. Tears, as unaccustomed to him as need or regret, filled his eyes. One fell on the blank page. Henry outlined it with his crayon.

“What’s it?” the baby asked him.

Henry laughed. “I can’t tell you,” he sang softly, “but I know it’s mine.”

She stared at him blankly.

“Draw!” she said, just sweetly enough not to sound too bossy.

“What should I draw?”

Henry looked at her. With his crayon still in his hand, he watched as she drew and drew: crazy colors, scribbled, dotted, zigzagged, crisscrossed, filling her page and then, without hesitation or doubt, spilling onto his own. She drew lines, over and over, her little fingers clutching first one crayon, then another, making a glorious field of every-colored grass. Henry picked up one of the crayons she’d put down and waited a long time, watching.

“Draw!” Haley said again, and finally Henry started to draw—one straight line, then a second one rising up out of the free, wild, colored grass, two perpendicular lines, the width of his hand apart. It was so simple. Henry drew the third line—parallel to the beautiful ground—and in an instant those lines completed a rectangle sitting in an open field, and with windows, a door, and perhaps a chimney, they could become a house.

||

A NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR

||

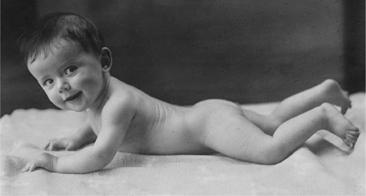

This novel started with a real photograph:

I found it, quite by accident, on a Cornell University website about the history of home economics. On the opening page of the online exhibit, among other thumbnail images, was the captivating snapshot of a baby with a beguiling smile and roguish eyes. I clicked on the photograph and learned that “Bobby Domecon” (the last name short for Domestic Economics) had been a “practice baby,” an infant supplied by a local orphanage to the university’s “practice house,” where college students learned homemaking, complete with a live baby whom they took turns mothering.

I know!

The first practice baby arrived at Cornell in 1919. She stayed for one year, as did dozens of subsequent infants. Cornell’s practice baby program continued until 1969, but it wasn’t the only one of its kind. During my research for this book, I learned that there were practice baby programs all over the country, so literally hundreds of infants started their lives being cared for by multiple mothers. For the most part, the approach seems to have been viewed as one that benefited the mothers as well as the babies, who were considered prime candidates for adoption when they were returned to their orphanages. There was, however at least one case that drew national attention when an Illinois child welfare superintendent questioned what the effects of this kind of upbringing might be. My wish for an answer is what inspired this novel.

||

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

||

For their encouragement and many insights, I am grateful to Suzie Bolotin, Barb Burg, Cathy Cramer, Liz Darhansoff, Sharon DeLevie, Lee Eisenberg, Frankie Jones, Jon LaPook, Kate Lear, and Kate Medina.

I could not have finished this book without the extraordinary kindnesses of Donna Ash, Richard Cohen, Marcus Forman, and Saud Sadiq, and I owe them my deepest thanks.

Michael Solomon not only encouraged, but inspired, informed, and explained.

Betsy Carter offered wisdom, brutal honesty, and limitless reassurance, sometimes on a minute-by-minute basis.

I am lucky enough to live with not one but three gifted editors. The fact that two of them are my children only adds to my sense of good fortune. Stephen, Elizabeth, and Jonathan Adler are the irresistible forces in my life.

The factual background for this book came from many sources, including conversations or emails with Marty Fox, Sandra Leong, Floyd Norman, Priscilla Painton, Rinna Samuel, and Kerry Sulcowicz. In addition to thanking them, I’d like to acknowledge my reliance on the following sources:

Up Periscope Yellow,

by Al Brodax;

Walt Disney’s Nine Old Men & the Art of Animation,

by John Canemaker;

Stir It Up,

by Megan J. Elias;

The Girls Who Went Away,

by Ann Fessler;

Walt Disney,

by Neil Gabler;

Walt’s

People,

vols. 1-4, ed. Didier Ghez;

Inside the Yellow Submarine,

by Dr. Robert R. Hieronimus;

Raising America,

by Ann Hulbert;

Good HAIR Days,

by Jonathan Johnson;

Becoming Attached,

by Robert Karen, Ph.D.;

The Good Housekeeping Housekeeping Book,

ed. Helen W. Kendall;

Mary Poppins, She Wrote,

by Valerie Lawson;

Dr. Spock: An American Life,

by Thomas Maier;

Hippie,

by Barry Miles;

You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me,

by Simon Napier-Bell;

Household Equipment,

by Louise Jenison Peet, Ph.D., and Lenore Sater Thye;

Opening Skinner’s Box,

by Lauren Slater;

Rethinking Home Economics,

ed. Sarah Stage and Virginia B. Vincenti;

The Illusion of Life,

by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston.

Back in 2001, students in a Human Development course at Cornell University collaborated with the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections to create an exhibit and website about the university’s rich tradition in the field of home economics. The result (still available online) provided a fascinating glimpse into a fading world that included practice apartments and practice babies and inspired this work of fiction. I will always be glad that Cornell made this wonderful material so accessible.

PERMISSIONS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

HAL LEONARD CORPORATION: Excerpt from “Runaway,” words and music by Del Shannon and Max Crook, copyright © 1961 (renewed 1989) by Bug Music, Inc., and Mole Hole Music (BMI)/Administered by Bug Music; excerpt from “Don’t Treat Me Like a Child,” words and music by Michael E. Hawker and John F. Schroeder, copyright © 1960 (renewed 1988) by Lorna Music Co. Ltd. All rights in the U.S. and Canada controlled and administered by EMI Blackwood Music Inc.; excerpt from “Who Put the Bomp (In the Bomp Ba Bomp Ba Bomp),” words and music by Barry Mann and Gerry Goffin, copyright © 1961 (renewed 1989) by Screen Gems-EMI Music Inc.; excerpt from “You Call Everybody Darling,” words and music by Sam Martin, Ben Trace and Clem Watts, copyright © 1946 (renewed) by Edwin H. Morris & Company, a division of MPL Music Publishing, Inc. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. Used by permission.

HAL LEONARD CORPORATION AND CHERRY LANE MUSIC COMPANY: Excerpt from “It’s Been a Long, Long Time,” lyrics by Sammy Cahn and music by Jules Styne, copyright © 1945 by Morley Music Co., copyright renewed and assigned to Morley Music Co. and Cahn Music Co. All rights for Cahn Music Co. administered by WB Music Corp. All rights outside the United States controlled by Morley Music Co. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

WILLIAMSON MUSIC O/B/O IRVING BERLIN MUSIC COMPANY: Excerpt from “They Say It’s Wonderful” by Irving Berlin, copyright © 1946 by Irving Berlin. Copyright renewed. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

LISA GRUNWALD is the author of the novels

Whatever Makes You Happy, New Year’s Eve, The Theory of Everything,

and

Summer.

Along with her husband,

BusinessWeek

editor in chief Stephen J. Adler, she edited the anthologies

Women’s Letters

and

Letters of the Century.

Grunwald is a former contributing editor to

Life

and a former features editor of

Esquire.

She and her husband live in New York City with their son and daughter.