The Judas Cloth

Authors: Julia O'Faolain

JULIA O’FAOLAIN

For Lauro

Who can swear that there will not come a pope so imbued with God’s spirit and that of our time … as to raise the flag of freedom on the towers of Castel Sant’Angelo?

N. Tommaseo to R. Lambruschini,

November 1831

Without the Pope, there can be no true Christianity.

Joseph de Maistre,

Du

Pape

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Acknowledgment

Note

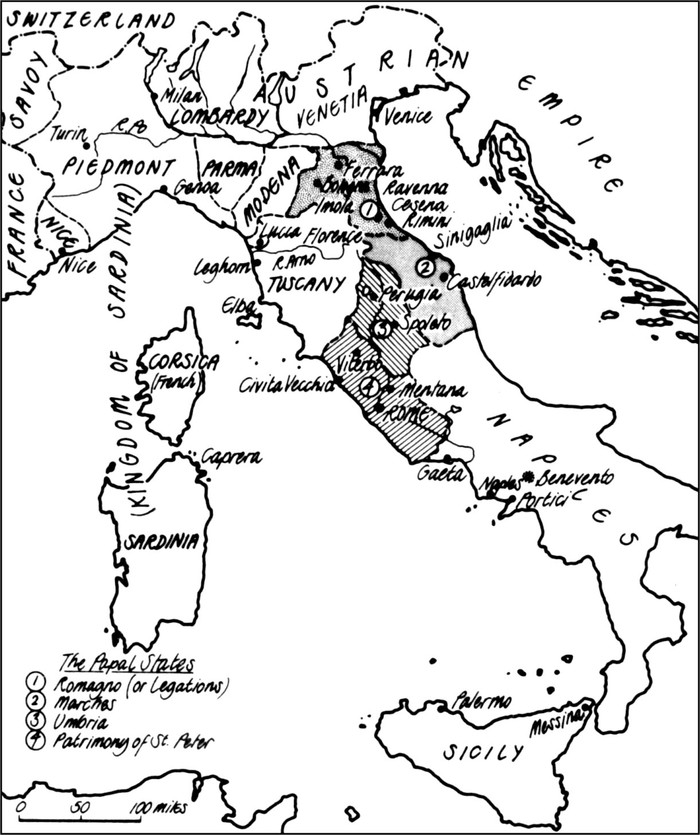

Map: Italy and the Papal State after 1815

List of the Principal Characters

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

Twenty-five

Twenty-six

Twenty-seven

Twenty-eight

Twenty-nine

Thirty

Thirty-one

Thirty-two

Glossary

About the Author

Copyright

I am grateful for the assistance of the Arts Council of Great Britain, and for that of the Rockefeller Foundation which granted me a residency at Bellagio.

Pope Pius IX – Pio Nono (1846–1878) – took to polemic as salamanders do to flame. His invective was biblical, and his enemies gave back as good as they got. Caught between their cartoons and his

anathemas

, the Catholic world was pushed ever further towards polarisation. The Right loved him for his torments, his piety and his charisma, and he has long – oddly long? – been a candidate for canonisation. The Left came to hate him.

I have tried to imagine what it was like to be a moderate dependant of his and, to give myself

freedom

, have invented several characters. I hope that the climate in which they move is close to that which prevailed in the Papal State during its final decades.

J. O’F.

Amandi, Cardinal: Friend of the Pope and patron of Nicola.

Andrea: Cardinal Girolamo Marchese d’.

Antonelli, Giacomo Cardinal: 1806–1876: from 1848 Secretary of State.

Bassi, Father Ugo: chaplain in papal armies of 1848 and later with Garibaldi.

Blount, Edward: Nicola’s companion in Paris during Bloody Week.

Bonaparte, Louis Napoleon: becomes Napoleon III.

Bonaparte, Napoleon Louis: his brother, dies of chickenpox in 1831.

Cesarini, Duke Flavio: earlier known as orphan called Diodato.

Cesarini, Donna Geltrude: Flavio’s mother.

Chigi, Flavio: nuncio to Paris.

Darboy, Archbishop Georges of Paris.

Diotallevi, Costanza: a spy.

Döllinger, Ignaz von: German theologian.

Dubus, Father: priest whom Amandi meets in Savoy in 1847.

Dupanloup, Bishop Félix of Orléans.

Gatti, Maria: girl whom Nicola falls for in 1849.

Gatti, Pietro: her son.

Gavazzi, Alessandro: a nationalist and Liberal preacher and chaplain in army.

Gilmore, Augustine: a classmate of Nicola’s at the Collegio Romano.

Giraud, Maximin: child visionary who sees Virgin in 1846.

Grassi, Father: a Jesuit.

Lambruschini, Cardinal Luigi: Secretary of State to Pope Gregory XVI, and right-wing favourite to succeed him. He lost to Mastai.

Lambruschini, Raffaello: a nephew of his, who keeps a diary.

Lammenais, the abbé: a Liberal Catholic thinker.

Langrand-Dumonceau, André, later Count: Catholic financier.

Manning, Cardinal Henry of Westminster.

Martelli: classmate of Nicola Santi at Collegio Romano.

Mastai-Ferretti, Giovanni Maria: later Pope Pius IX.

Mauro, Don: an unfrocked priest.

Mérode, François Xavier de: Chamberlain, then Minister for Arms.

Mortara, Edgar. Jewish child kidnapped by papal authorities.

Nardoni: police lieutenant in Imola, spy.

Oppizzoni, Cardinal Count Carlo: Archbishop of Bologna.

Passaglia, Carlo: a Jesuit theologian at the Collegio Romano.

Paola, Sister: nun who first appears as unnamed girl during revolution of 1831.

Reali, il canonico: dissident priest.

Randi, Monsignor Lorenzo: papal minister of police.

Rossi, Count Pellegrino: Pio Nono’s chief minister, murdered in November 1848.

Russell, Odo: unofficial agent of British Government.

Sacconi, Monsignore: nuncio to Paris.

Santi, Nicola: later Monsignore.

Stanga, Prospero: later Monsignore.

Stanga, Count: his father.

Stanga, Contessa Anna: father’s second wife.

Verità, Don Giovanni: a Liberal priest.

Vigilio, Don: a spy.

Viterbo: Edgar Mortara’s uncle.

After midnight a funeral took place with furtive pomp. It was an event likely to puzzle any stranger who chanced to witness the defiant advance of the red-draped, four-in-hand hearse and the throngs of trudging mourners who growled out angry prayers and held tapers up like spears. Behind them, a two-hundred-strong cavalcade of carriages bore prelates and members of the city’s papal (‘black’) aristocracy. Houses were lit up and flowers thrown from windows. But the mob was there too, stationed all along the way from St Peter’s to San Lorenzo Outside the Walls. At first its mood was uncertain. Then a song rose jeeringly:

‘Addio,

mia

bella

,

Addio

!’

Scuffles broke out and the police had to stop demonstrators seizing the corpse. ‘Long live Garibaldi!’ was the cry. ‘Death to the priests!’ and ‘Pitch the swine in the Tiber.’

‘Carogna

!

Into the river with his carcass!’

Driving through the whitewash gleam, which had transformed their grimy old city into a whited sepulchre, disheartened the prelates. They were burying an epoch with their last Pope Prince. Pius IX, having reigned for thirty-two years, had set a record for longevity which left his predecessors’ in the dust. His reign had been riven by paradox and this funeral was its last, for when he died three years ago, his household had not dared cross the hostile city and bury him where he had asked to be laid. How come, marvelled watchers, that the three-year-old corpse didn’t explode? Mummified, was the answer, like the papacy itself. Embalmed and boxed in.

*

Reports of police connivance – only six demonstrators had been charged! – reached the provinces in the high colour of parable. Pope Pius, when alive, had been inclined to wrap himself in the seamless robe of Christ,

and the robe, a metaphor for papal power, had been rent when the Kingdom of Italy seized his state.

Two principles had clashed: a people’s right to determine its destiny and the Pope’s to territorial independence. This latest Italian failure to defend papal dignity fuelled arguments afresh. The robe had been spat on and Christ vilified in his Vicar’s person! The new pope protested angrily. Clergy, up and down the country, stiffened their opposition to the regime and men who had tolerant leanings shelved them. This was no time for give and take. Even personal loyalties must be sacrificed.

Father Luca, who had been hiding the diary of his dead benefactor, the abate Lambruschini, inside a wrapper entitled

Experiments

in

Crop-

Rotation

,

now lost his nerve. What if it were found? By friends who would reproach him with not destroying it – or, worse, might want it published! The abate had been a Liberal priest. A great but sad man, born out of his time, he had hoped that, after his death, his diary might safely see the light of day. But now he had been dead seven years, and Father Luca worried lest, somehow – the devil had his ways – it should fall under some dangerous and alien eye. He himself couldn’t sit in judgment on it. He was a simple priest, a labourer’s son educated at the abate’s expense. But reports of the mob’s insults recalled older ones about how, many years ago, at the start of his reign, Pius too had been a Liberal and been worshipped by that same Roman mob. Lambruschini had described him walking in among them in his white robe and how, as he passed, they sank to their knees in the dung-wet streets. ‘Long live the Angel pope!’ was then their cry. Father Luca, his curiosity piqued, took down the book.

the

diary

of Raffaello

Lambruschini

:

Rome, 1846

In Rome, just after his election, I glimpsed the new pope. I was on a balcony with my uncle, the defeated candidate, who was scanning the crowd with the eye of a man who knew the odds. For ten years he had been Cardinal Secretary of State and, in practice, the most powerful man in the realm – which was why

he

was not elected pope. Cardinal Secretaries rarely are. Being too visible, they rouse resentments. He should have known this. Yet loss of power shocked him and I, who had not been on terms with him, felt a surprised impulse of pity.

‘Viva

Papa Mastai,

the people’s friend!’

It was half-prayer and half-cheer. 1846 looked to be a miraculous year for we had, or thought we had, a Liberal pope. Political and religious hope fused in that cry while my uncle, Luigi Cardinal Lambruschini, sat still as a pillar of salt.

I disdained his doubts. To be sure the new pope’s love-transaction with the crowd was hazardous – but how can men who have not defied their limitations conceive of God?

Once a fritter-vendor, scrambling onto the roof of his booth, came so close that we smelled frying oil of incalculable age. He cradled his balls in a – pagan? – gesture of celebration and I saw my uncle wince. Anarchy, he clearly felt, had been unleashed and his own handiwork undone, for Pius was releasing conspirators whom it had taken

his

spies miracles of ingenuity to catch.

All around us, seminarians in bright cassocks – scarlet, white, purple, black – craned and flexed as if turning themselves into human flags. Only when His Holiness exchanged jokes with our fritter-seller did I see a pulse tremble in my uncle’s neck. A particle of flesh, by defying his will, reminded me that our new pope’s was more wayward. I knew this because I belonged to a group which had secretly worked to get him elected. Mastai-Ferretti knew nothing of our reasons for choosing him to succeed to Peter’s throne. These can be summed up in one word: humanity. Like Peter, he had proven fallible, flexible and, we hoped, open to change.

My uncle was not. Sitting beside him, I was aware of having betrayed my kind for – kinship apart – he and I were men who put principle above personal ties, and I knew that if he could have understood my disloyalty, he would have condoned it. So there I sat, inwardly twisting like Judas on his rope. Once he pressed my hand.

‘Sursum

corda,’

he whispered. ‘Let’s raise our hearts.’ But I, his Judas, thought of the schoolboy pun, ‘raise the rope’ –

corda

– and feared he had seen inside my head.

It was only later, in the gaunt cavern of his dining room, that I thought I saw tears. The candelabra, however, were inadequate and the light too dim for certainty. A year later, at the time of the so-called Jesuit plot, I wondered if he had had a hand in that, but guessed him to be too shrewd.

*

The words ‘Jesuit plot’ made Father Luca blench and so did the reference to the dead pope as a ‘Liberal’. The abate had been writing in and for happier times and Father Luca felt a pang of nostalgia for his patron’s lightness of spirit. Maybe it was as well he’d died when he had.

Moving to a window, he watched fork-tailed swallows wheel. The air was still. Sounds carried across surprising distances and, down valley, a skipping rhyme was being thrummed on some threshing floor. Sour words reached him with painful clarity.

Pyx! Pax! Pox! St Peter’s on the rocks!

His leaky boat won’t float!

Pyx! Pax! Pox!

The abate’s great fear had been that of adding to the boat’s distress. This was why he left Rome. He had liked to joke that this Tuscan retreat was like the islands to which the Emperor Augustus had exiled adulterers and that he, rather than adulterate honest certainties, had embraced silence as well as exile. And indeed, after the débâcle of ’49, he had published nothing more contentious than a treatise on silk worms. He had gone on writing, to be sure, but ‘for the drawer’. But now, thought Luca, let it be some other drawer than his! The abate’s trust weighed on him and, remembering that he knew a dependant of the Cardinal Prefect of the

Congregatio

Indicis,

he determined to send him the diary and get the matter off his conscience. Surely the abate would have understood?

the

diary

of Raffaello

Lambruschini:

Controversy stifles charity. I learned this as I watched my uncle meet

his

Calvary. That evening, he talked of a universe of pain through which humanity must struggle in search of lost unity.

We must have sat up later than usual for the footmen were visibly falling on their feet when he leaned towards me and whispered: ‘Revolution is part of God’s plan. The French one was a punishment and we too shall soon be tested. Blood will flow here!

Sangue

!’

he hissed with such relish that I was amazed. ‘The

popolo,’

he gloated, ‘will get more than they bargained for.’ Then he pursed his old man’s mouth

until it looked like a chicken’s anus and went red with malice. My revulsion shocked me. In the end a distrust for zeal – my own included – led to my renouncing public office. Yet what I had already done by promoting the candidacy of Mastai-Ferretti was to have long-tailed consequences.

People who remember papal Rome tend to talk of a paradise or a prison. My own recollection is of a sleepy little place choked by rotting brocade with a population – in the year of Mastai’s election – of 170,000 souls, few of whom knew much about the world outside their city gates which were kept timorously locked at night. It had its own system for telling time. A twenty-four-hour day ended at the Ave Maria, half an hour after sunset, and so varied with the seasons.

Memories differ and so do maps. I have two of the old town before me as I write. On one the Tiber flows down the left while on the other it festoons up the other side, carrying a sailboat upstream from Ripetta to Ripa Grande: a draughtsman’s whimsy intended no doubt to show that, even after the advent of steamers, trade was plied at a sluggish pace – as indeed it was. Weed-webbed and gilded – in memory – by the sun of a perpetual siesta, Rome droused to the flap of wet laundry and the chomp of oxen chewing the cud in ‘the Cow Field’ which was how citizens called the Forum. At night it slept through antiphonies of caged nightingales, disturbed only by the odd clopclop of a carriage fetching guests home from a

conversazione

in some noble palace. Productive activity was rare. Strangers came to dawdle and dabble, and in the margins of memory there is always an Englishwoman with an easel. Pyrotechnists prospered as did stage carpenters. Rome, in short, was a stage on which we learned to exhibit ourselves, and my first moment of revulsion came when, as a very young cleric, I saw a senior prelate go down on his hands and knees, bark like a dog and entertain Pope Gregory by waggling his reverend rump. His influence with His Holiness depended, I was told, on the alacrity with which he was prepared to play the buffoon.

Gregory was my uncle’s pope, and his need for such solace may have been due to distress at the harsh measures which my uncle persuaded him to adopt. Our regime was doomed. Our government knew this, but could not agree to diminish God’s sway over His state. In moments of unrest it appealed for help to the Austrian Army.

It was in this climate that some of us began to gather data about possible candidates for the succession:

papabili.

Transitions are risky and the last bad disturbances had erupted just before Pope Gregory’s

own election during the

sede

vacante

of ’31. How had our candidates behaved then? One had been in the very eye of the storm: Archbishop Mastai-Ferretti whose record we now proceeded to scan. I still have documents whose existence might surprise him.

1831

PROCLAMATION

by Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferretti, nobleman of Senigallia, Ancona and Spoleto.

By the Grace of God and the Holy Apostolic See, Archbishop of Spoleto, Commendatory Abbot of Santa Croce in Sassovivo, Domestic Prelate to H.H. Gregory XVI and Assistant at the Papal Throne.

Following our provinces’ happy restoration to their lawful Sovereign and trusting in the pious submission of our flock, we wish to make known our concern that respect be shown to all rebels who hand in their arms in token of their intention to return to the paternal embrace of the Supreme Pontiff …

30 March 1831

Spoleto, Palace of the Archbishop

Archbishop Mastai-Ferretti reread his old proclamation where the words ‘paternal embrace’ had split apart. Had someone …? No, just wind and weather. The thing had been rained on then, no doubt, split in the May sun. He thought of the May procession and the play of light on embroidered banners. The Austrian High Command had questioned the wisdom of holding it so soon after the disturbances, but the archbishop had prevailed. Last spring he had been a bit of a hero.

Passing a café, he nodded an acknowledgment to risen hats. A hen scuttled under his feet and a woman darted out to collect it, then withdrew with a movement not unlike the hen’s. In a garden another woman was throwing water to keep down the dust. Shutters slapped open. The siesta hour had passed and, up in the

Rocca,

a bugle announced some changeover in the prisoners’ routine.

The archbishop’s stroll had brought him to a palace which he should have remembered to avoid. Here too shutters had opened and a liveried servant was hanging out a bird cage. Now the sensitive, tapir’s nose of the old marchesa slid into sight and her eye caught his.

‘Afternoon, Monsignore.’

‘Afternoon, Donna Maria.’

He walked unhappily on. They had been friends, but not since Easter.

Trying not to speed his step, he remembered, with residual pique, how a mutiny at the

Rocca

had been used by local notables to worm permission from him to recruit a Civic Guard. The marchesa’s son had led the delegation. After all, said Don Gabriele, His Eminence the Legate was known to favour mobilising the citizens.

‘Arm the people against the people?’ The archbishop could not openly criticise the legate’s judgment.

It was Ash Wednesday and there was a smudge of penitential ash on the delegates’ foreheads.

‘General Sercognani’s force is approaching,’ Don Gabriele argued.