The Judgment of Paris (26 page)

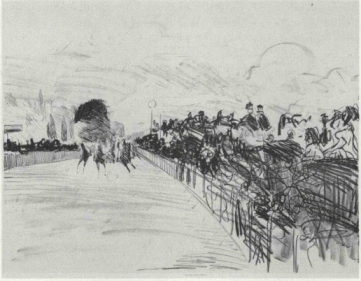

Lithograph of The

Races at Longchamp

(Édouard Manet)

If

The Races at Longchamp

was stimulated in part by engravings in journals like

Le Sportsman,

a second of Manet's paintings from the summer of 1864 owed even more to the popular press. For the past few years a Confederate privateer, the C.S.S.

Alabama,

had been roaming the seas in search of Union merchant ships. All told, sixty-eight of these vessels had been sent to a watery doom, with a loss of six million dollars in Union trade revenues. By the spring of 1864, the

Alabama's

deadly hunt had brought it into the waters of the English Channel. Then in June, a short time before Manet departed for Boulogne, the legendary privateer appeared in the French port of Cherbourg.

Through the spring of 1864, the Civil War had remained a grim battle of attrition. At the beginning of May, the Union Général Ulysses S. Grant started his summer campaign by moving his 120,000-strong Army of the Potomac into central Virginia, where it engaged Robert E. Lee's numerically inferior forces in the Wilderness, a harsh terrain where more than 17,000 Union casualties were sustained. A few days later and ten miles to the southeast, in the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, Lee again checked the Union advance, inflicting almost 20,000 casualties on the Army of the Potomac.

Meanwhile the war was being fought on other fronts. Gideon Welles, the U.S. Navy Secretary, had eight warships scouring the oceans for the

Alabama,

whose remarkable exploits had been splashed across the pages of British, French and American newspapers. On June 11, while patrolling the English Channel, one of these vessels, a sloop of war named the U.S.S.

Kearsarge,

received reports that a Confederate ship, soon confirmed to be the

Alabama,

had arrived in Cherbourg for the recoppering of its hull and the repairing of its boilers. Two days later, the

Kearsarge,

commanded by John Winslow, was sighted several miles off the coast of Cherbourg, where it waited for the

Alabama

to weigh anchor and enter the Channel. Battle was finally engaged on a Sunday morning, June 19, when the

Alabama,

though low on ammunition and still barely seaworthy, steamed out of Cherbourg, bravely living up to the motto on her great bronze wheel:

Aide-toi et Dieu t'aidera

("God helps those who help themselves"). After a battle lasting ninety minutes—during which time the two warships fought starboard to starboard in increasingly diminishing circles while spectators gathered on high ground along the shore to watch—the

Alabama

was sunk by the superior firepower of the

Kearsarge,

which was outfitted with two 15,700-pound Dahlgren smoothbore cannons. Three French pilot boats and a British steam yacht named the

Deerhound

rescued Raphael Semmes, captain of the

Alabama,

and fifty of his crew. But the career of the great Confederate privateer was ended as the burning ship sank stern-first into the waves and then disappeared from sight.

*

Even though French sympathies rested largely with the

Alabama,

the sea battle created as much excitement in France as the victory of Vermouth at Longchamp had two weeks earlier. Before the month of June was out, engravings of this naval battle had appeared in numerous French newspapers, including

L 'Universel

and

Le Monde illustré.

Within a few weeks, another view of the engagement was also offered to the public. In the middle of July, a painting by Manet entitled

The Battle of the U.S.S. "Kearsarge" and the C.S.S. "Alabama"

went on show in the window of a shop in the Rue de Richelieu owned by the publisher Alfred Cadart. Inspired by the engravings and news reports, Manet had created his own version of the scene, one placing a French pilot boat in the foreground and, beyond it, the

Alabama

swamped and smoldering in the blue-green waves. Unlike

The Races at Longchamp,

the painting was not based on either firsthand observation or

plein air

sketches, but it was animated, like the racing scene, by both popular illustrations and public sentiment. In his search for success and acclaim, Manet had left behind the corridors of the Louvre and turned to the events—albeit quite extraordinary ones—that were occurring in the world around him.

Manet arrived in Boulogne a day or two after the work went on show in Cadart's shop and, setting up his easel in the harbor, began his seascapes. One of these,

Departure of the Folkestone Boat,

featured a more modest vessel than the

Alabama,

a steam packet that plied the Channel between England and France. This work was probably not painted entirely out of doors, since Manet placed the captain, in what would have been a flagrant breach of the rules, on the boat's bridge, a detail indicating that he did not paint exactly what he saw but rather cobbled the painting together from various of his sketches and memories. Another of his paintings,

Seascape at Boulogne,

featured a school of porpoises in the foreground and a variety of ships and scudding sailboats in the distance.

Still, the charms of working

en plein air

were not inexhaustible. And while Boulogne had various attractions besides its harbor, its ships and the Établissement des Bains, Manet seems to have found its cultural allurements less than stimulating. Within a few days of arriving in Boulogne he wrote to a friend in Paris, the engraver Félix Bracquemond: "Although I'm enjoying my seaside holiday, I miss our discussions on Art with a capital A, and besides there's no Café de Bade here."

7

Desperate for news of friends such as Baudelaire, he appealed to Bracquemond for the latest gossip.

Fortunately for Manet, his interest was piqued by the arrival in Boulogne of the U.S.S.

Kearsarge,

which dropped anchor a short distance offshore and began playing host to numerous tourists. "The ship is pretty well crowded with a fine lot of people," wrote one crewman, Marine Corporal Austin Quinby, in his journal, "many of them from the country and have on their Sunday go-to-meeting clothes and are very nice looking."

8

Another observer, one of the

Kearsarge's

coal-heavers, was less impressed with the visitors, recording that "they go up and down the decks chattering like so many monkeys, and they go through as many antics as I ever see a Clown go through in a circus."

9

Manet was one of these visitors. Ferried out to the

Kearsarge

by a pilot boat, he went on board a day or two after arriving in Boulogne. He made sketches of the scene and then painted two impressions of the sloop as she lay at anchor: one an ink-and-watercolor, the other an oil painting entitled

The "Kearsarge "at Boulogne.

The latter included a sailboat navigating a foreground of choppy, aquamarine-tinted sea and, on the horizon line, several pilot boats nearing the

Kearsarge,

which was little more, in this view, than a menacing black silhouette. The painting also included a curious anomaly. The flags and streamers on the prow and masts of the

Kearsarge

blow in one direction while the sails on the boats billow the opposite way, offering more evidence that Manet was not painting exactly what he saw—and perhaps explaining why the young Édouard had proved such an abysmal recruit for the naval academy.

Manet's efforts by the seaside received encouragement when he learned that

The Battle of the U.S.S. "Kearsarge" and the C.S.S. "Alabama

"had received a good review from Philippe Burty in

La Presse,

the daily newspaper in whose pages Paul de Saint-Victor usually dripped his venom. The thirty-four-year-old Burty was a progressive art critic whose articles had appeared in, among other journals, the

Gazette des Beaux-Arts.

10

During the late 1850s he had championed the art of etching, but more recently his attentions had turned to Oriental art: he would later coin the

word japonisme

to describe the craze for all things Japanese. Manet was well aware that Burty's words carried much weight. He went so far as to write Burty from Boulogne to thank him, expressing the hope that more such reviews would come his way. "I'm grateful to you," he wrote, "and hope the proverb 'one swallow doesn't make a summer' will not apply to us!"

11

After several weeks in Boulogne, Manet finally returned with his family to Paris, bringing back with him on the train a collection

of plein-air

sketches and several completed canvases. He also returned with an apparent determination to steer his new course in art, painting popular, topical scenes without any of the learned and ironic allusions to the art of past centuries that undergirded works such as

Le Déjeuner sur I'herbe

and

Olympia.

In fact, one of his first paintings upon returning to Paris was of a bowl of fruit—pears from the orchard in Gennevilliers of his cousin, Jules De Jouy.

Manet made a change to his personal as well as his artistic life in 1864. Soon after returning from the coast, he moved out of the three-room apartment in the Rue de l'Hôtel-de-Ville that for the past four years had been his home. With Suzanne and Léon, as well as Suzanne's grand piano, he took new lodgings in the Boulevard des Batignolles, still within short reach of the Gare Saint-Lazare, and still in the heart of the district. Once installed, he began making plans for an exhibition of his works that would reveal this new artistic direction.

"The painter's part is to come to the aid of history," Meissonier once wrote. "Thiers speaks of the flash of swords. The painter engraves that flash upon men's minds."

12

Meissonier, in the summer of 1864, was still hard at work turning Adolphe Thiers's words—his description of Napoléon and his triumphant cuirassiers at the Battle of Friedland—into a painting. While Manet was able to illustrate the combat between the

Kearsarge

and the

Alabama

in four short weeks, Meissonier, typically, was taking far more time on his own battle scene. He made small oil sketches of everything from the hooves and haunches of the individual horses (the painting, like

The Campaign of France,

would feature more than a dozen of them) to tiny details such as the hat with which Napoléon salutes his troops.

13

He also began sculpting various of the horses in wax. These figurines, which stood some eight or nine inches high, were impressive works of art in themselves. Meissonier twisted wire frameworks into shape, then covered them with pellets of warm beeswax that he proceeded to model with his fingers. The features of the horses—the flared nostrils, the eyes, even the teeth—were next sculpted with minute precision, while small leather bridles were fashioned to fit over their heads. If Manet's horses in

The Races at Longchamp

were suggested by a few quick splodges of color, the warhorses of the Grande Armée would take shape on Meissonier's easel only after being put through their paces in an endless series of models and prototypes. He was so laboriously precise that he forced one of his horses to hold an awkward position for such a long stretch that he completely exhausted the animal.

14

These intricate preparations meant that

Friedland,

though keenly awaited by the public and the critics alike, would not be finished on time to appear at the Salon of 1865. However, Meissonier was also creating several other works, including a pair of small panel paintings—

Laughing Man

and

End of a Gambling Quarrel

—which marked the return of his musketeer style. The former work simply portrayed a man in seventeenth-century clothing (sword, sash, lace collar, wide-topped boots and wide-brimmed hat), the latter a pair of men in identical costume sprawled on the floor after having exchanged rapier thrusts. This last scene was set in an elegant interior—enormous fireplace, tapestried wall, upholstered chairs—that looked like something out of the seventeenth century but was in fact a room in the Grande Maison. Meissonier's house, with its needlepoint tapestries, heavy antiques and acres of wood paneling, made a fitting backdrop to his musketeer paintings. Its rooms were works of art in themselves. "Some of the rooms are fit to be framed," enthused Gautier (whose own taste in interior decoration inclined toward Turkish sabers, cuckoo clocks and the various exotic curios brought back from his expeditions to Algeria).

15

Meissonier was still crafting his musketeer paintings for the simple reason that he needed the money. He had been paid very large sums for

The Battle of Solferino

and

The Campaign of France

—25,000 and 85,000 francs respectively. But together the paintings had used up three or four years of work. With

Friedland

threatening to take equally long, he clearly needed other work to finance his ostentatious manner of living. Meissonier spent, on average, 60,000 francs per year. Most of these huge sums disappeared due to his passion for, as he put it, "piling stones on top of one another."

16

Construction bills for the Grande Maison and its assorted outbuildings had devoured hundreds of thousands of francs since the original structure had been purchased almost twenty years earlier for a modest 18,000 francs.

17

Meissonier was as much a perfectionist with his house as he was with his paintings: only the best materials and most exacting craftsmanship would do. And so just as he often scraped paint from a canvas, he forced his builders to knock down and rebuild any additions and alterations that failed to please him—often at great inconvenience and even greater expense. The accounts for the building works at the Grande Maison for the two years between 1854 and 1856—a dense manuscript of 837 pages—include the master mason's constant scribbled refrain, "change made by the owner."

18