The Judgment of Paris (43 page)

4A.

The Birth of Venus

(Alexandre Cabanel)

4B.

Olympia

(Édouard Manet)

5A.

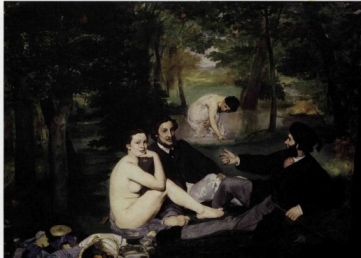

Le Déjeuner sur I'herbe

(Claude Monet)

5B.

Le Déjeuner sur I'herbe,

originally entitled

Le Bain

(Édouard Manet)

6A.

The Races at Longchamp

(Édouard Manet)

6B.

Friedland

(Ernest Meissonier)

7A.

The Siege of Paris

(Ernest Meissonier)

7B.

The Railway

(Édouard Manet)

I

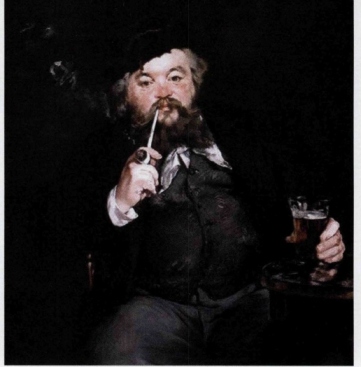

8A.

Le Bon Bock

(Édouard Manet)

8B.

Bathers at La Grenouillère

(Claude Monet)

T

HE PROTESTS AND petitions launched in the spring of 1867 seemed to have borne fruit when the results of the 1868 jury's decisions were made public: more than 5,000 works of art—paintings, sculptures, engravings, photographs—had been submitted, of which more than eighty-three percent were accepted, including 2,587 paintings.

1

The successful artists included Camille Pissarro, who had desperately needed some good news after his rejections in 1866 and 1867. With his riverbank views lingering unsold in his studio, and with two young children to feed, he had been forced to earn money by painting awnings and shop signs. In April, however, he received a letter from Daubigny reporting that both of his pictures had been admitted.

2

These canvases, both landscapes, were views of Pissarro's newly adopted home of Pontoise, a market town on the River Oise, eighteen miles northwest of Paris. Another

refusé

from the previous two Salons, Renoir, likewise found favor with the jury, as did Manet's elegant friend Edgar Degas. In keeping with his love of ballet and opera, Degas had submitted a dreamy costume-piece,

Mademoiselle Eugénie Fiocre in the Ballet "La Source?'

which was based on a scene from a ballet performed with much success at the Paris Opéra in 1866.

Both of Manet's submissions,

Young Lady in 18GG and Portrait of Émile Zola,

were accepted without, apparently, either questions or confabulations. The jurors were perhaps reluctant to decline these works lest they bring down on their heads the wrath of the bellicose subject of the second portrait, since Zola had been engaged to cover the Salon for

L 'Événement illustré,

a journal that had risen from the ashes of

L 'Événement

following its suppression by the authorities at the end of 1866. In any case, Manet would make a return to the Palais des Champs-Élysées for the first time since the controversy over

Olympia

three years earlier.

Despite the new munificence on the part of the jury, the results still managed to yield a few disappointments. Paul Cézanne, as ever, failed to have a canvas accepted. One of Cézanne's friends explained his failure by averring that he had "no chance of showing his work in officially sanctioned exhibitions for a long time to come. His name is already too well known; too many revolutionary ideas in art are connected with it; the painters on the jury will not weaken for an instant."

3

This perhaps overestimated Cézanne's notoriety, but his arrestingly unique style—combining Courbet's use of the palette knife with Manet's thick outlines and sharp juxtapositions of color—produced undeniably brusque-looking canvases with bold but sometimes virtually indecipherable images. The subject matter of his work was frequently as alarming as the style. In 1868 he painted

The Murder,

a disturbingly brutal scene in which two figures, one wielding a dagger, are shown violently attacking a third. He had also made preparatory sketches for

The Autopsy,

featuring a man's naked corpse stretched on a mortuary slab as a bearded doctor prepares to set to work. Such eerie-looking scenes had little chance of finding a place on the walls of the Salon. But Cézanne had been persistent, going to the Palais des Champs-Élysées each March, as another friend wryly observed, "carrying his canvases on his back like Jesus with his cross"

4

—and then bearing them, stamped with a red R, back to his grubby studio. Such martyrdom began to grate. Cézanne's constant rejection made him even more bitter and cantankerous than usual on the rare occasions when he could be tempted to join the company in the Café Guerbois. Asked by Manet on one such circumstance whether he intended to submit anything to the Salon, Cézanne had retorted: "Yes, a pot of shit!"

5