The Judgment of Paris (70 page)

Stewart did not enjoy his prize for long. He died in April 1876, only a few weeks after taking delivery of

Friedland.

The work remained in Stewart's mansion (which occupied the site where the Empire State Building would eventually be built) until it was sold at auction in New York in 1887. Judge Henry Hilton, the executor of Stewart's estate, purchased it for $69,000—the equivalent of more than 300,000 francs—and immediately donated it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. More than a century later,

Friedland

is still in the museum, where it hangs in a corridor beside another great equestrian canvas, Rosa Bonheur's

The Horse Fair.

Visitors to the Metropolitan Museum can admire it immediately before passing into the "Manet Room" (featuring nine of Manet's canvases) only a few yards away. The "two opposite poles of art" have been brought together within steps of one another.

Stewart and Hilton were not the only American tycoons with a taste for Meissonier. William H. Vanderbilt, the shipping and railway magnate, would purchase seven of his paintings and also sit for a portrait; all were shipped to New York to grace his block-long Greek Renaissance townhouse, "The Triple Palace," on Fifth Avenue. The most exalted estimate of Meissonier's worth was offered, though, by a Frenchman. In 1890, the year before Meissonier's death, Alfred Chauchard, owner of the Grands Magasins du Louvre, an enormous department store in the Rue de Rivoli, paid a staggering 850,000 francs when

The Campaign of France,

formerly owned by Gaston Delahante, came onto the market. To get some perspective, the entire annual budget for the Paris Opéra was 800,000 francs, a sum sufficient to maintain an eighty-piece orchestra along with seventy ballet dancers and sixty choristers.

22

This stratospheric price made

The Campaign of France

the most expensive painting ever purchased during the nineteenth century, by a painter either living or dead. Almost two decades after the Universal Exhibition in Vienna, Meissonier's signature had still been worth that of the Bank of France.

Meissonier died at his Paris mansion in the Boulevard Malesherbes on January 31,1891, a few weeks shy of his seventy-sixth birthday. He was survived by his children and by Elisa Bezanson, whom he had married two years earlier, following Emma's death in 1888. After a Requiem Mass at the church of the Madeleine, his body was taken for burial to the cemetery of La Tournelle in Poissy. The following year Henri Delaborde, a distinguished art historian, delivered Meissonier's eulogy at the annual meeting of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. "Meissonier's life flowed on for half a century," claimed Delaborde, "in the splendor of a glory without eclipse, in the confident possession of success of every kind, and homage in every form . . . Everything was exceptional in that brilliant career, from the constant chorus of admiration which acclaimed it, to the universal emotion with which the news of its close has been greeted, both in France and abroad."

23

Meissonier had the good fortune to die while his reputation was still intact and unsurpassed. But within a decade or two, his reputation—and his prices—had collapsed. "Many people who had great reputations," he once gravely observed, "are nothing but burst balloons now"

24

—and he himself provides the most cautionary and startling example. By 1926 the art historian Andre Michel, a professor at the College de France, was able to write: "The case of Meissonier is one that gives us pause to reflect about the variations of taste and the vicissimdes of glory. No painter was more adulated during his lifetime . . . His reputation was global. But what remains today of all this magnificence?"

25

Two decades later, Lionello Venmri's two-volume history of nineteenth-century French art,

Modern Painters,

made no mention of him whatsoever: Meissonier had vanished from the history of French art like a murdered enemy of Stalin airbrushed from an official Soviet photograph.

When not expurgated from the history of French art, Meissonier has been cast as one of its villains, an evil genius who, among his various sins, frustrated the career of Édouard Manet—the man praised by Michel as someone "who played the role of the heroic annunciator, the initiator of a new art."

26

Meissonier's place has thus become an invidious one, that of the counterpole to more progressive artistic movements of the second half of the nineteenth century. Forty years after Michel, a French writer named Jean-Paul Crespelle, author of numerous popular guides to Impressionism, even managed to make Meissonier an opponent of Delacroix, who was in fact one of his best friends and supporters.

27

But loathing of Meissonier has known few boundaries, including that of historical accuracy. As Jacques Thuiller, a modern-day professor at the College de France, wrote in 1993: "Rare is the artist on whom more prejudice—and even hatred—has accumulated than Meissonier. Not long ago the mere act of looking at one of his works was considered worthy of excommunication."

28

Meissonier was even despised by a staunch aesthetic conservative like John Canaday, the chief art critic for the

New York Times

during the 1960s and a bitter opponent of the Abstract Expressionists and other exponents of modernism. Canaday confessed himself enraged at the thought that "while this mean-spirited, cantankerous and vindictive little man was adulated, great painters were without money for paints and brushes."

29

In 1983 a French connoisseur was even heard advocating the incineration of Meissonier's canvases.

30

In two generations, Meissonier went from the most revered painter in Europe—and one of the world's most famous Frenchmen—to an artist who caused such embarrassment to the French establishment that in 1964 a marble statue of him unveiled four years after his death was unceremoniously removed from the Louvre on orders from Andre Malraux, Charles de Gaulle's Minister of State for Cultural Affairs. Even more demeaning was the fate of another statue of Meissonier, cast by Emmanuel Frémiet in 1894 and unveiled near the church in Poissy: it was melted down for scrap.

Thuiller has claimed that Meissonier's excesses—his enormous wealth as well as the excruciating conscientiousness of his paintings—became "a target for the new generations." The art critic Gustave Coquiot, who was born in 1865, the year of

Olympia,

summed up the opinion of many younger artists appalled by the extravagant prices paid for Meissonier's works by men such as Stewart, Vanderbilt and Chauchard. Author of books on Van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec, and a man who once posed for the young Pablo Picasso, Coquiot claimed that Meissonier was "the representative choice of the limitless stupidity of the bourgeoisie and the

nouveaux riches.

. . . He possessed in exact proportions the ignominies of his time; and he threw into the face of the

nouveaux riches

of two hemispheres his low smears, a puerile and silly tedium that they found so agreeable. Thus we have Meissonier, a bad painter for businessmen and vulgar upstarts! Yes, all of that, and nothing more."

31

Coquiot's hateful shrieks ring a little false when set against the

nouveau riche

adulation of the Impressionists: in 1912 Louisine Havemeyer purchased Degas's

Dancers Practicing at the Bane

for 435,000 francs, or a little more than $95,000, which made it 55,000 francs more expensive than

Friedland.

The difference between Meissonier and Manet was actually over artistic aims and techniques, not side issues such as fat bank balances and great painters (in Canaday's melodramatic scenario) "without money for paints and brushes." The decade between 1863 and 1874—the years between the Salon des Refusés and the First Impressionist Exhibition—had witnessed a struggle between the votaries of the past and those of

la vie moderne.

This struggle concerned rival ways of painting as well as, ultimately, rival ways of seeing the world, and it would result in the greatest revolution in the visual arts since the Italian Renaissance. The contest was shot through with amusing ironies as well as questions about our most confident value judgments. It is superbly ironic, in the first place, that at a time when a group of artists began experimenting with new methods of capturing their "sensations" of objects through slurred colors and summary brushwork, the most celebrated painter in France should have been constructing his own railway track for the purposes of understanding with micrometric accuracy the precise motions of a galloping horse's legs—and then attempting faithfully to convey this movement on his canvas with one of the steadiest and most deliberating paintbrushes in the history of art. That the cultural gatekeepers condemned the first procedure as roundly as they celebrated the second seems perversely unthinkable from a point of view—the one that has prevailed for the past century—that takes for granted that what one sees is not as important in the visual arts as how one sees or expresses it.

To these gatekeepers, however, our reversal of their aesthetic judgments, and the collapse of Meissonier's reputation at the expense of those of Manet and the Impressionists, would have been equally unthinkable. Meissonier is far from alone, though, in suffering a posthumous reputation that cruelly gainsays his contemporary acclaim. Numerous other artists and writers have paid for the applause of their lifetimes with silence and obscurity after their deaths. Removing the idols of the previous generation from their pedestals has long been a favorite pastime of cultural historians—though rarely does it happen quite as literally as in the case of the two statues of Meissonier. The French offer a striking literary parallel to Meissonier in Anatole France, their most popular writer in the two or three decades before his death in 1924, yet someone now devoid of an influence or a following.

32

Such harsh reevaluations provide a matter for sober reflection not only for today's cultural icons but to all those who realize that posterity will always have the last word.

There is perhaps a final irony in Manet and Meissonier's careers. Before we mock the seemingly inexplicable appeal for nineteenth-century Salon-goers of Meissonier's

bonshommes

in their quaint costumes, it is worth considering whether some of the more recent admiration for Impressionist portrayals of "modern life" may be steeped in something of the same yearning for a bygone time. Meissonier's spurred and booted cavaliers being served drinks outside a country tavern spoke to nineteenth-century Parisians in the same language of gentle nostalgia that Monet's parasol-clutching woman wading through a field of poppies, or Manet's barmaid under a chandelier at the Folies-Bergère, speak to many museum-goers today. The painters of modern life created, in the end, the same consoling visions of the past.

More than a century after their deaths, Manet "endures in glory, flooded with light and fame" while Meissonier gathers dust in museum storerooms. Yet for all his self-regard and swollen sense of artistic destiny, Meissonier may well have been resigned to his obscure and dismal place in history. "Life," he once sighed. "How little it really comes to."

33

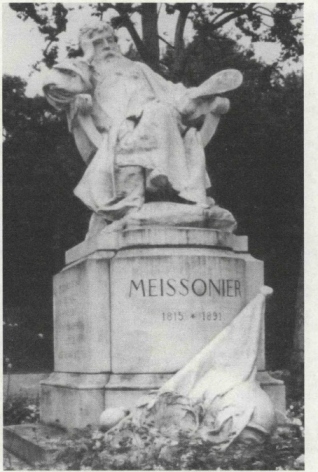

One of the few places that still commemorate him is, suitably enough, Poissy. Here, in what is now an industrial town where automobiles have been manufactured since 1902, Meissonier's well-tended grave, planted in summer with cyclamen, can be found in the cemetery of La Tournelle. The gravestone features a bas-relief bronze portrait and an inscription that proudly announces him as the winner of the Grand Medal of Honor in 1855, 1891 and 1878. A short distance away, a quarter-mile-long stretch of road has been christened the Avenue Meissonier. To its west, in the grounds of the former abbey, thirty acres of wooded slopes and gravel paths have been known since 1952 as the Pare Meissonier. Frémiet's bronze statue of Meissonier may have been knocked from its pedestal and melted down for scrap, but in the park the painter's image endures in the form of the enormous marble statue that Malraux banished from the Louvre. Brought to Poissy in 1980 and placed in the middle of a flower bed, it shows the artist sitting cross-legged in one of his antique armchairs, his left hand holding his palette and his right supporting his head.

Carved in 1895 by Antonin Mercie, this statue is curiously revealing. The base of the pedestal, inscribed "MEISSONIER 1815—1891," features a disconcerting paraphernalia: an empty breastplate, a fallen standard, and a wreath of laurels that seems to have tumbled from the artist's head and landed on the ground. From his armchair, Meissonier himself gazes glumly at a modern world that rushes heedlessly past his stern marble glare. The monument is, more than anything else, an image of acquiescence and defeat, of an artist grimly accepting his unhappy encounter with posterity.