The King of the Vile

The King of the Vile

by David Dalglish

BOOKS BY DAVID DALGLISH

THE HALF-ORC SERIES

The Weight of Blood

The Cost of Betrayal

The Death of Promises

The Shadows of Grace

A Sliver of Redemption

The Prison of Angels

The King of the Vile

THE SHADOWDANCE SERIES

Cloak and Spider (novella)

A Dance of Cloaks

A Dance of Blades

A Dance of Mirrors

A Dance of Shadows

A Dance of Ghosts

A Dance of Chaos

THE PALADINS

Night of Wolves

Clash of Faiths

The Old Ways

The Broken Pieces

THE BREAKING WORLD

Dawn of Swords

Wrath of Lions

Prologue

A

lric Perry awoke gasping for air, his arms pushing against the heavy blanket atop him.

“What is it?” his wife Rosemary asked as she rolled to face him. “Is it that dream again?”

Shifting so his back was to her, Alric stared at the bare wood wall, unable to close his eyes. Too much risk of falling asleep. Too much risk of returning to the dreaming world.

“No,” he lied.

He lay there until morning, enduring the bleak hours as the moon faded and the sun rose. When the first hint of light slipped beneath the cracks of their heavy curtain, Alric rose out of bed and splashed water across his face from the washbasin they kept in the adjacent room. Glad he couldn’t see the redness of his eyes, he ran his fingers through his long black hair, trying to straighten it into something manageable.

“Is this what you want?” Alric whispered into the silence. “Is it really?”

Rosemary stirred at the same time he heard the first of his two sons walking across the creaking wood floors to the kitchen. Alric smiled a bitter smile. Rosemary always seemed to know when the kids would wake. There were crops to be tended, his work in the fields slacking as of late, but he didn’t go out, nor did he make himself something to eat. He stood there, waiting for his wife to get out of bed. Her hair a mess, she glanced at him as she slid off the hay mattress.

“You should have gone back to sleep,” she said, easily reading his red eyes. “It’s only a dream.”

Alric grunted, said nothing. Still in her shift, Rosemary passed through the kitchen on her way out the front door, pausing to rustle the hair of their eldest, Bartholomew. Alric found it hard to breathe as he watched. He was going to do it. He was actually going to do it.

Having finished relieving herself, Rosemary came back inside to change her clothes. When she saw him standing there, unmoving, she frowned.

“What is it?” she asked.

“I’m going,” he told her.

She froze. “No, you’re not,” she told him.

He shook his head, unsure of what else to say. It was crazy. He knew that. She knew that, too.

“Damn it,” Rosemary said, storming toward him. “It’s a dream, Alric, a stupid dream. You can’t leave me here, you can’t…”

He tried to wrap his arms around her, but she pushed him away, her eyes widening.

“Don’t,” she said. “You can’t leave us like this. The harvest starts next week, and we’re short on hands as it is.”

“We’ve a spare bed, and good food,” Alric said. “There’s plenty of boys in town who’ll work for both.”

“But what if you don’t come back? You know what everyone’s been saying. The angels are killing everyone they pardoned. Everyone. You’re safe here in Ker, but there...”

“It was only one night,” Alric insisted. “And it doesn’t matter. I still have to go.”

His wife’s lower lip quivered, but she steeled herself. She’d always been a tough woman. It’s what attracted Alric to her in the first place.

“You think this is what Ashhur wants you to do?” she asked him. “He wants you to abandon your wife? Your kids? Does that sound like the right thing to do?”

Again he shook his head, helpless against her. How could he explain it? There was no way to show her, no way to convince her. The dreams had come for months now, their clarity and strength increasing tenfold over the past week.

“Please stop,” he said. He caught their two little boys watching from the kitchen, pretending not to see, and it made his heart ache. “Rose…I can’t sleep. I can barely eat. Whatever this is, it’s tearing me apart. I need to do something.”

Rosemary looked away, crossed her arms.

“Come on boys,” she said, suddenly hurrying into the kitchen. “Your father needs some time alone. Dress yourselves so we can go to grandpappy’s house.”

Alric stayed in their bedroom, coming out only when they were leaving. He knelt so he could hug his sons, kiss the tops of their heads, and say goodbye. Rosemary spoke without words, her message instead conveyed by the severity of the slamming door. It rattled the house and left Alric with shaking hands and watery eyes.

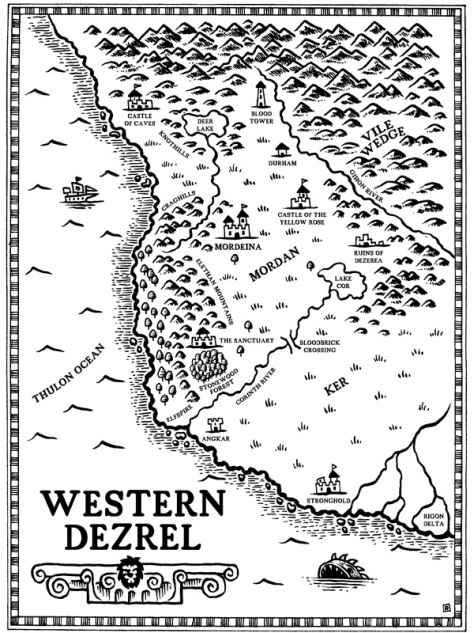

Packing his supplies took little time. They’d had many prosperous harvests the past few years, so the jars he stuffed into his rucksack would not be missed. He brought only a single change of clothes, knowing any more than that would be a luxury he couldn’t afford to carry. It was a long walk to Mordeina, after all. He did pack a second pair of boots, new ones he’d purchased a week ago. He’d argued with Rosemary that it hadn’t been because of his dreams. Holding them in his hands, running his fingers over the leather, he wasn’t sure if it’d been a lie or not.

He filled two waterskins at the stream running through the back of their land, then hoisted his rucksack over his shoulders. The weight was heavier than he expected, and he grunted.

So what?

he told himself. If he could endure the dreams, he could endure a sore back and blistered feet. With no other delay, he began walking down the long worn path leading north from their property. He didn’t even risk a look back at their house. It wasn’t that he expected to never return. It was that he knew the slightest glance behind might cost him his courage.

Waiting for him at the crossroad leading to town was Rosemary’s father, Jacob.

“I can’t say I’m surprised,” Jacob said. He was a wealthy man, his clothes fine but well-worn. His hands and face were weathered from countless hours in the fields. Hard blue eyes bore into Alric, and there was little sympathy in them.

“Just doing what I think is right,” Alric said.

“I’m sure you are.” Jacob looked back toward his own lands, the largest surrounding the little village of Greenbrook. “She won’t be waiting for you. I’ll make sure of that. She needs a man to take care of her, one who won’t run off because of childish nonsense.”

Alric bit his tongue to hold back his anger. He’d known this would happen if he left. His marriage had always been rocky, and Jacob never truly approved. To him, Alric was just an outsider, a foreigner. To go now, to abandon his family...

“You do what you think is best,” Alric said, dipping his head in respect. Putting his back to his father-in-law, to the entire village of Greenbrook, Alric started walking northeast.

Not far off the worn path was a well-maintained road leading to the Bloodbrick Bridge. He followed it, the rucksack feeling heavier than ever. This was it. The miles steadily passing beneath his feet, he tried to feel some optimism. He was doing what his god wanted, after all. Why should he not rejoice? He sang some songs the traveling priests had taught him, and they cheered his heart a little. It never lasted. Such cheer, such thoughts, never lasted when the after-images of the dreams flashed before his eyes.

No, whatever Ashhur wanted him to do, it wouldn’t be easy. It wouldn’t be safe. He was far too fearful a man to rejoice in what, deep in his heart, he felt was a death sentence.

It was five miles to the Bloodbrick, and he was not alone as he traveled. Several times he had to shift off the road so wagons could pass him by, all heading the opposite direction. After a few hours, a wagon rolled along from behind him, driven by an elderly man.

“Headed to the bridge?” the man asked. His teeth and hair were missing, but his eyes were lively.

“I am,” Alric said.

“Hop on. Could always use someone to listen to my prattling.”

Alric tossed his rucksack into the tiny wagon, which was stuffed with bags of flour, and climbed aboard.

“Soldiers got to eat,” the old man explained, having caught Alric’s wandering eyes.

“Of course,” Alric said. Before spurring the donkeys onward, the old man reached to his belt and pulled a long dagger halfway out of its sheath.

“Don’t be getting any funny ideas,” he said. “Been on the road longer than you’ve been alive, so keep your hands off me, and off my shit, and we’ll get along swell.”

“Understood,” Alric said. “I’m only glad to rest my feet for a little while.”

“How far you been walking?”

“Since Greenbrook.”

“Hah!” The trader set the wagon to rolling. “You’re sore from that? I once had to walk all the way from Angkar to Angelport. Let me tell you something, when you’re walking that long a journey, sore feet’s the easiest of your problems...”

He continued on, and Alric only half-heartedly listened. He kept his focus on the bridge coming into view. The Bloodbrick was the only major way across the Corinth River, which formed the border for the nations of Ker and Mordan. If Alric wanted to get to Mordeina, Mordan’s capital, he’d need to cross, but he doubted that’d happen without incident based on what he saw.

Thousands of soldiers lined the river, their gathering of tents so thick he could barely see across to the other side. Multiple barricades were set up before the bridge, constantly patrolled. Alric felt his heart thud in his chest at the sight of it all. There were so many people, not just soldiers, but traders, camp followers, even some children and animals lurking around the edges. It was like one swelling, shifting organism, and the thought of being inside it made Alric sick. He’d never done well with crowds, hated merely having friends over too long in his house. To go through that many...

“Well, here we are,” the trader said. “You looking for someone?”

“No,” Alric said, hopping off the wagon and reaching for his rucksack. “I’m hoping to cross.”

The elderly man’s laughter followed him as he approached the soldiers. He stayed on the road, his arms crossed over his chest for protection. From both sides of the road came shouts, some joyful, some not. One of the camp followers, a pretty miss with fiery red hair, made a move toward him until she saw his simple farmer’s clothing. Her face remained pleasant, but Alric saw the dismissal in her eyes, and it made his stomach twist.

At last he reached the barricades, and was ordered to halt by the guards stationed there.

“What’s your business?” the man in charge asked him as another roughly yanked the rucksack off his back and began searching through his things. A third soldier patted him down for weapons. He found none.

“Travel,” Alric said. “Not business. I wish to visit Mordeina.”

“You a member of any trading guilds?”

He shook his head.

“Are you a servant of a noble lord, or of any noble lineage?”

“No,” Alric said, again shaking his head. “I’m a farmer. That’s all.”

The second soldier shoved the rucksack back into his arms and nodded to the others.

“The border’s closed,” the soldier said. “I’m sorry, but if you aren’t nobility, and aren’t a merchant, you’re not crossing.”

For a brief moment Alric felt relief. He could go home. He could abandon this stupid notion that he was somehow important. That relief was met with shame, and the stubbornness Alric had carried with him all his life.

“You don’t understand,” he said. “I have to cross.”

“I’m sure you do,” the soldier said, motioning to the other two. “But it don’t matter.”

They pushed him back, making way for the next in line to be checked. Alric watched, feeling as if the entire world were shrinking in around him. He had to cross. He had to.

Making his way back down the road, he walked until the commotion around the Bloodbrick was but a murmur on the wind. Telling himself it’d be all right, that Ashhur would protect him, he veered off the road and into the field beyond. The bridge was the only way to cross the Corinth for wagons and horses, but any river could be crossed if one could swim it. Soldiers patrolled the water’s edge, but once he was a mile out from the bridge Alric found a safe space to cross. By then night had fallen, and coming with it was a chill hinting at the approach of autumn. Alric stared across the wide, murky water, focusing on the dry land on the other side.

“Please,” he prayed to Ashhur. “Please, I’m doing this for you, so…don’t let me die. Is that a fair enough request?”

One of the priests he’d met in Greenbrook had told him to never pray for something he wasn’t prepared to have granted. If going on living was something he wasn’t prepared for, he hoped the river swept him away into the night. Tightening the straps to his rucksack, he took a step.

“Damn that’s cold,” he said, jerking his foot back out. Hopping up and down, he berated his childish hesitation. The water was cold? What did he expect, a bubbling hot spring?