The Kite Fighters (5 page)

Authors: Linda Sue Park

Kee-sup was so busy with the King's kite that he did not have time to fly his own. Young-sup went alone to the hillside nearly every day with his tiger. It was not only for the pleasure of flying. Now he was practicing with a purpose.

The New Year was approaching. It was the biggest holiday of the year. The celebration lasted for fifteen daysâgifts were exchanged, grand meals were eaten, visitors came and went. But this year the holiday had gained extra significance for Young-sup.

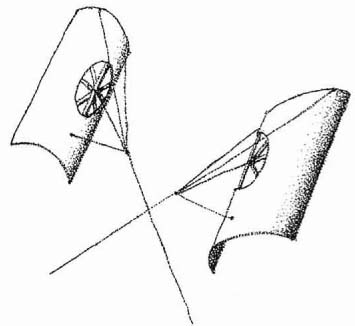

Every year the holiday culminated in a kite festival. Hundreds, even thousands, of people traveled to the royal park in Seoul to fly kites. And the most important part of the festival was the kite fights.

Young-sup had seen them for the first time the

year before. Two competitors stood within large circles marked on the ground. The object of the contest was to get the opponent's kite to crash by bumping or knocking it. To ensure fair play, and to render a decision if both kites crashed at the same time, judges observed the competition.

The most skillful fliers could sometimes maneuver their kites so that their lines, taut and strong, actually cut through the lines of their opponents. This did not happen often, but when it did, it produced the most exciting victory. As the defeated kite was cut loose and floated off into the sky, dozens of boys chased after it, for the kite now belonged to whoever could reach it first.

Every day, under his tutor's watchful eye, Young-sup struggled to concentrate on his lessons. Normally he prided himself on his studies; indeed, of the two brothers, it was Young-sup who most enjoyed poring over the texts for the challenge of learning the words by heart. But these days all he could think of was the coming festival.

When the lesson finally ended, Young-sup would stand, bow his head, and wait. Sometimes the tutor spent a few moments tidying the scrolls or preparing for the next day's lesson. Young-sup looked like the picture of the dutiful scholar, but every muscle was

tense with impatience and inside his head he was screaming, "Hurry up! Forget about all that! Leave!"

When the tutor had stepped through the door, Young-sup was finally free. He walked politely for a few steps, until he saw that the tutor had made the turn for the outer court. Then Young-sup rocketed to his room, grabbed his tiger kite, and raced out to the hillside.

He had but one goal: To be the winner of the boys' competition this year.

***

Young-sup's tiger floated far, far overhead, using nearly all of the line on his reel. He relaxed and let the kite fly almost on its own; practicing was hard work, and he needed a rest. He was alone on the hillside again; Kee-sup was at home studying, trying to catch up on all the lessons he had missed while making the King's kite.

Idly, Young-sup glanced at the landscape. Far down the road that wound around the base of the hill he could see a dark blot approaching. It was too big to be just one person; it must be a group of people. As they slowly drew nearer, Young-sup could make out more details.

Scarlet uniforms. A palanquin. The royal standard atop the palanquin.

The King!

At least this time I'll he ready,

thought Young-sup. He began to reel in the line, wishing that Kee-sup were with him.

By the time the King's procession had advanced up the hillside, both the kite and Young-sup were down, the kite with its line wound neatly on the reel and Young-sup on his knees with his forehead touching the ground.

The King dismounted from the palanquin. "Rise," he said. "Where is my kite?"

Young-sup rose to his feet. His mind worked furiously to find the right words. The King's kite was nearly finished; Kee-sup had only the smallest of details to attend to. "Your Majesty, my brother begs your forgiveness. He knows you are waiting, but heâhe wishes to make sure the kite is perfect in every way for you."

The King nodded. He turned to his courtiers and gestured with one hand. "All of you are to take the palanquin and wait at the bottom of the hill."

"Your Majesty does not wish any of us to remain?" The man who seemed to be the adviser spoke.

"No. I have no need of assistance. I am merely going to fly a kite." The King seemed impatient.

Young-sup left his kite on the ground and began to follow the others. "Not you," said the King. "You stay."

***

The guards, servants, and adviser marched down the hill with the empty palanquin. Then the King turned to Young-sup. "I am thinking that I should practice before I fly my new kite."

"Your Majesty is very wise." Young-sup hesitated. "If there is any way I can be of assistance..."

The King glanced down the hill at his coterie, then back at Young-sup. "Yes. There is one thing, to begin with. I recall you and your brother last time. You were calling out, shouting to each other. In my travels through the city streets I have heard other boys talk like this."

He paused for a moment. Young-sup thought that the King looked almost embarrassedâthen chided himself for having such a thought. Why would the King feel ashamed in front of a lowly subject like himself ?

The King continued, "I wish to learn this kind of speech. It cannot be done in the presence of others. But here, on this hillside, I wish for us to speak to each other as you did to your brother."

Young-sup was horrified. Talk to the King like a

brother? Me

mumbled, "I could try. If that is what Your Majesty desires."

The King spoke with what sounded almost like a

sigh. "It is what I desire, but perhaps it is not possible. For either of us."

An awkward silence fell between the two boys. Young-sup felt fidgety but forced himself to remain still. He looked down the hill at the Kings attendants and wondered what it would be like to be a boy giving commands to grown men.

Giving commands ... Young-sup's face brightened suddenly. He bowed his head to the King. "Your Majesty?"

"Yes?"

"You could make it a command."

"A command?" The King looked puzzledâthen broke into a grin. "Ah, I see! It must be done correctly, then. What is your name?"

"My father is Rice Merchant Lee, Your Majesty. My name is Young-sup, and my brother is Kee-sup."

"Lee Young-sup. When we are alone, you are to speak to me as you speak to your brother. I hereby command you!"

And for the first time Young-sup and the King laughed together.

***

The King was a good flying student. While lacking

Young-sup's natural instinct for flying, he still possessed a better understanding of the wind than Kee-sup had at first. His attempts to launch the tiger kite on his own were unsuccessful, but he did very well at keeping the kite in the air once Young-sup helped him get it there. On Young-sup's advice, the King took off his heavy robe to allow him freer movement. All afternoon the two boys took turns flying, until the sun began to dip below the hilltop.

It was not so difficult for Young-sup to teach the King about flying. To teach him about speaking was another matter entirely.

Young-sup began by explaining. "You know the polite form of speakingâhow you use different words to speak to someone older or someone in a higher position? For example, when I thank my father for something, I must use formal wordsâ'Father, I appreciate your kindness.' But to our servant Hwang I might say, 'Thanks, Hwang.'"

The King was holding the reel. He looked doubtful and stared up at the kite for a moment. Then his face cleared a bit. "I remember my lessons, when I was about eight years of age. The court ministers were most annoyed. They kept repeating that I no longer had to address anyone as a superior."

Young-sup listened in astonishment. "Not even

your parents?" As soon as the words left his mouth, he regretted them.

The King spoke solemnly. "My father, His Late Majesty, had passed on to the Heavenly Kingdom. When I became King, the ministers said that no one, not even my mother, the Dowager Queen, was considered my superior."

Young-sup tried to imagine such a thing. He couldn't, and shook his head in wonder.

The King went on, "Instead, my tutors explained that I must always consider carefully whatever I say. They told me that every time I speak, I represent the nation.

"I did not think much of it then, when I was youngâI had only to learn it, to please them. But now I am aware that I have spoken in only one way for as long as I can remember. Whereas everyone else, it seems, has different ways of speaking. This is what I wish to learnâthese differences."

Young-sup thought hard. How could he explain something that came to him as naturally as breathing? He was silent so long that the King finally spoke.

"Perhaps," His Majesty said wistfully, "it is not something that can be learned."

Young-sup scuffed at the hard ground with his heel a few times to loosen the soil, then sat down. The

King sat next to him. Young-sup showed the King how the reel could be planted in the earth; when the wind was just right, as it was today, the kite could fly even without a flier.

They watched the kite for a few moments. Finally Young-sup asked a question. "Do you ever get angry?"

"Of course."

"What do you say when you get angry?"

"I express my displeasure. If I am angry enough."

Young-sup rolled his eyes and groaned inwardly. He had to think of another way. "Your Majesty, am I truly free to do as I wish now? To teach you the way I speak with my brother?"

"Of course. I have ordered you to do so."

"All right. Let's try something different."

Young-sup picked up the reel, handed it to the King, and stood; the King followed his lead. Then, as the King looked up at the kite, Young-sup shoved him off balance and snatched the reel away from him.

The King staggered backward, then tripped and fell. The watchful guards at the bottom of the hill responded immediately. They charged up the hillside to protect and give aid to the King.

The King jumped to his feet. Without taking his eyes from Young-sup's face, he raised his hand and

stopped the guards with a single gesture. They waited where they were, halfway up the hill.

"If it was the reel you desired, why did you not ask me?" The King's voice was stern, his face unsmiling. "It was unnecessary to push me. I would have given it to you."

Young-sup ignored the rebuke. "Your Majestyâwhen I pushed you just now, what were you thinking? Your exact words, as they were in your mind."

The look on the King's face changed from angry to confused. "I was thinking, Why did you do that?"

"Good!" Young-sup exclaimed. "If it were my brother, that is what he would have said. He would have said something like, 'Why did you do that, you leper?'"

"Ah! So he would have said the words in his mind, just as they were?"

"Yes, that's right."

The King frowned, considering. "And this is how you always speak?"

"No. As I said, I must still use the polite form of address to my parents, my tutorâanyone older. But to others my own age or younger, yes. And also with my brother." Young-sup paused for a moment. "Although now that he has been capped, I'm supposed to speak politely to him as well."

The King nodded. He waved the guards back down the hill, then turned to Young-sup and took a deep breath. "All right. I shall try now." He grabbed for the reel. "Give that back to me, you ... you leper!"

Young-sup laughed. He held the reel away from the King, then dashed away. The King chased after him. The two boys dodged around the hillside, exchanging insults and laughter as they ran.

At last they slowed, then stopped, still panting and laughing. The King sobered somewhat and beckoned his entourage. As they brought his palanquin back up the hill, he turned to Young-sup. "I'll watch for your kite," he said. "When I see it, I'll come out. If I can."

The King's men had drawn within earshot now. The King straightened up and spoke loudly in a regal voice. "Tell your brother I expect him at the palace soon. You are to come with him."

But his eyes were twinkling, and Young-sup had to suppress a giggle. "Yes, Your Majesty. It shall be so."

The two boys and their father walked in silence. Under Kee-sup's arm, wrapped carefully in a linen cloth, the precious kite was making the journey to the palace.

Kee-sup's use of the gold leaf had been daringâand successful. Using a stiff brush and the blunt edge of a knife, he had flicked and spattered the gold leaf over the whole surface of the kite paper. The rain of minuscule gold dots had resulted in a fine sheen that glowed faintly when the light touched it. Once the kite was in the sky, the sun's rays would make it glitter and shine like real dragon scales.

But this had not been tested. The boys had argued about whether or not the kite should be flown before being presented to the King. Young-sup, of course,

had been eager to try it out, but Kee-sup had prevailed, fearful of damage to the kite.

Now, as they walked toward the palace, there was little to say. Either the King would like the kite or he would not. Nothing they did or said now could change that.

But Young-sup knew that the kite was more than just a gift for the King. In a few years Kee-sup would take the difficult series of examinations required of those who wished to be employed by the royal court. Such coveted positions were awarded based on the examination results; however, it was well known that those in favor at the court were looked on with added grace. If the King were pleased with the kite, it would do nothing to hurt Kee-sup's chances.