The Knight in History (13 page)

Read The Knight in History Online

Authors: Frances Gies

What gave Geoffrey’s narrative dramatic power in its own time and appeal for subsequent ages was his medievalizing of the story. King Arthur’s court is the court not of a sixth-century British chieftain but of a twelfth-century king, modeled after contemporary Anglo-Norman prototypes. He has vassals, whom he rewards with gifts of land. After conquering France, he divides it among his nobles, exactly as William the Conqueror had in fact done with England a few decades before Geoffrey wrote. The nobles live in castles, first built in Europe in the ninth century and in England in the eleventh, and Arthur’s court is crowded with knights. Knights and nobles comport themselves in accordance with twelfth-century chivalric ideas. Arthur “developed such a code of courtliness in his household that he inspired peoples living far away to imitate him.”

53

The knights wear their own livery and armorial devices, and “women of fashion” adopt the colors of their knights; “they scorned to give their love to any man who had not proved himself three times in battle.”

54

At the great plenary court at Caerleon after Arthur conquered France, “the knights planned an imitation battle and competed together on horseback, while their womenfolk watched from the top of the city walls and aroused them to passionate excitement by their flirtatious behavior,”

55

exactly as really happened in twelfth-century tournaments.

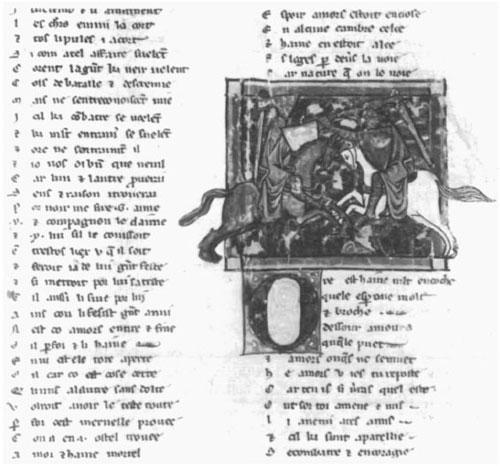

BATTLE OF YVAIN AND GAWAIN, ILLUSTRATING CHRÉTIEN DE TROYES’S

YVAIN. (PRINCETON UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, GARRETT MS. 125, F. 52)

Geoffrey’s immensely popular work was widely adapted and translated into several vernacular tongues. The outstanding adaptation was that of a scholar named Wace, born at about the same time as Geoffrey, in the Isle of Jersey, and educated in the Norman city of Caen.

56

Wace dedicated his

Brut (Brutus)

,

*

a poetic paraphrase of Geoffrey’s prose history completed in 1155, to the famous queen of France and England, Eleanor of Aquitaine. Written in French in the form used by the poetic romance, Wace’s work told the story vividly and dramatically, with detailed descriptions of battles and feasts, much dialogue, and an emotional content not present in Geoffrey’s original. He added several details to the story, from Celtic myth, the most significant of which was the Round Table.

57

Carrying Geoffrey’s medievalizing further, Wace made Britain a model feudal kingdom and described battles as clashes of mounted knights in shock combat. Wace’s Arthur had matured into the paragon of knighthood, in the tradition of the romances: “a very virtuous knight,” “a stout knight and a bold…and large of his giving. He was one of Love’s lovers; a lover also of glory…. He ordained the courtesies of courts, and observed high state in a very splendid fashion.”

58

MARRIAGE OF YVAIN AND LAUDINE. CONTRARY TO THE TRADITION OF COURTLY LOVE, LOVERS IN THE ROMANCES USUALLY MARRIED.

(PRINCETON UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, GARRETT MS. 125, F. 38)

Shortly before the end of the century a Saxon poet and cleric called Layamon wrote an adaptation of Wace, the first account of Arthur in English vernacular. Layamon expanded and embellished the story, notably with an account of the construction of the Round Table, and a detailed description of Arthur’s final transportation to Avalon. The wounded Arthur is made to say:

“‘And I will fare to Avalon, to the fairest of all maidens, to Argante the queen, an elf most fair, and she shall make my wounds all sound; make me all whole with healing draughts. And afterwards I will come again to my kingdom, and dwell with the Britons with [much] joy.’ Even with the words there approached from the sea a boat, floating on the waves; and two women therein, wondrously fair: and they took Arthur and put him quickly in the boat and departed….”

59

Such was the contribution of the chroniclers to the King Arthur story, a fragment of shadowy history upon which they embroidered an imperishable substance of myth and romance. From the chroniclers the work now passed into the hands of the poets.

60

The imagination and wit of Chrétien de Troyes (fl. 1165–1190) lent a new mystical-magical aura to the story.

61

Besides using Wace, Chrétien took from Celtic sources the major figures of Lancelot and Perceval, Camelot as Arthur’s capital, and the theme of the Holy Grail. Tristan was already a figure familiar to poets, one of whom, known only as Thomas of England, seems to have introduced him into the Arthurian story in about 1170.

All these additions wrought a change in the role of Arthur. The central character of Geoffrey of Monmouth was reduced to the role of a bystander in Chrétien’s five romances

(Erec et Enide, Cligès, Lancelot, Yvain

, and

Perceval)

, in each of which the central character was a knight-errant. His adventures included not only tournaments and combats but supernatural experiences with dragons, giants, enchanted castles, spells, and magic rings. Chrétien showed the influence of troubadour poetry in his idealization of secular love as well as in his poetic technique. Lancelot’s adulterous affair with Guinevere and Tristan’s with Iseult were the essence of “courtly love.”

Other poets took up the Arthurian theme. Notably, the minnesinger Wolfram von Eschenbach painted a vivid picture of King Arthur’s court and the Round Table and further developed the theme of the Grail, building his story on the knight’s search, beyond adventure, human love, and even the brotherly spirit of the Round Table, for the meaning of life.

62

The last significant medieval addition to the Arthurian literature was an anonymous collection of adaptations in French prose produced in the thirteenth century, known as the Vulgate Cycle, which added the final, and in many ways crowning, Arthurian figure, Galahad.

63

Translated into many languages, the Vulgate Cycle provided the chief source of Sir Thomas Malory’s English-language

Morte d’Arthur

, which was published in 1485, virtually marking the end of the Middle Ages.

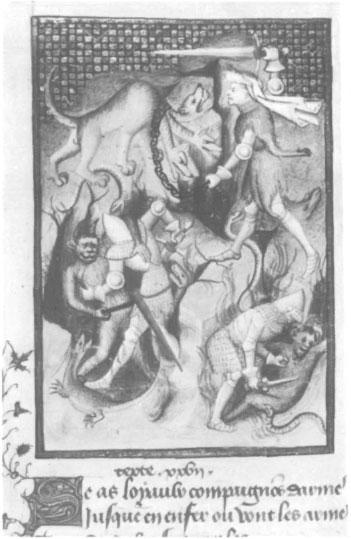

THE KNIGHTLY VIRTUES:

THE KNIGHT IS LOYAL TO HIS COMPANIONS EVEN AGAINST THE FORCES OF HELL.

(BRITISH LIBRARY, HARLEIAN MS. 4431, F. 108V)

Aside from its intrinsic literary value, and its influence on European thought and culture, chivalric literature played an important part in the history of knighthood. It contributed to fixing the self-image of the knight and to strengthening his esprit de corps. It helped define standards for knightly behavior, some of which were implicit in knightly life-style itself, some, the religious and moral, set down in the codes of chivalry that began to appear late in the twelfth century.

The rules of conduct that the poetry of the troubadours prescribed were mainly social: a knight should be courteous, generous, well-spoken, discreet, faithful in the service of love; he should have “

pretz e valors

,” excellence and worth, as well as good sense.

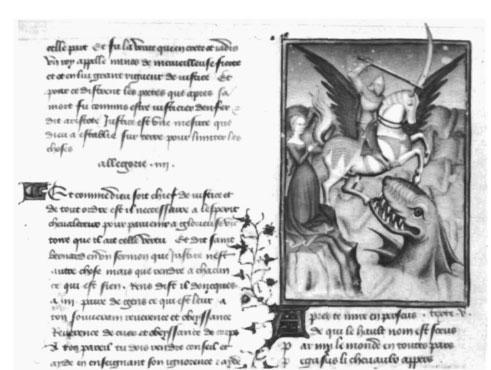

THE KNIGHTLY VIRTUES:

THE KNIGHT RESCUES THE MAIDEN IN DISTRESS.

(BRITISH LIBRARY, HARLEIAN MS. 4431, F. 98V)

From the

chansons de geste

came a different model, also secular: a knight should be brave, loyal, and honorable, and he should perform deeds that would earn him glory.

The guidelines added by the Arthurian romances supplied a religious note reminiscent of the Peace of God and the “soldier of Christ” of the First Crusade.

When Chrétien de Troyes’s Perceval leaves home to seek King Arthur, his mother tells him, “You will soon be a knight, my son…. If you encounter, near or far, a lady in need of help, or any damsel in distress, be ready to aid her if she asks you to, for all honor lies in such deeds. When a man fails to honor ladies, his own honor must be dead…. Above all, I beg you to go to church, to pray to Our Lord to give you honor in this world and grant that you so lead your life that you may come to a good end.”

64

He finds a sponsor who knights him, fastens on his spurs, girds on his sword, and kisses him, saying that he has given him

La plus haute ordene avec l’espee

Que Diex ait faite et commandee

C’est l’Ordre de chevalerie

Qui doit estre sanz vilonnie

.

65

(With the sword, the highest Order

That God has created and ordained,

The Order of chivalry

Which must be without wickedness.)

The sponsor echoes Perceval’s mother in his advice: “If you find a man or a woman, or an orphan or a lady, in any kind of distress, you’ll do well to lend them your aid if you know how and are able. And one more lesson I have for you…go willingly to church to pray to Him who made all things.”

66

The Vulgate Lancelot carried the advice further. When Lancelot expresses his desire to become a knight, the Lady of the Lake explains the significance of knighthood to her foster son: Once men were equal, but when envy and covetousness came into the world and might began to triumph over right, it became necessary to appoint defenders for the weak against the strong, and they were called knights. “They were the tall and the strong, and the fair and the nimble, and the loyal and the valiant and the bold.” A man thus chosen had to be “merciful without wickedness, affable without treachery, compassionate toward the suffering, and openhanded. He must be ready to succor the needy and to confound robbers and murderers, a just judge without favor or hate. He must prefer death to dishonor. He must protect the Holy Church, for she cannot defend herself.”