The Knight in History (19 page)

Read The Knight in History Online

Authors: Frances Gies

But the vital center of the vast network remained the house in Jerusalem, near the Golden Gate and the Dome of the Rock. A German pilgrim of 1165, John of Würzburg, was impressed by the great stables that could lodge “more than two thousand horses or a thousand five hundred camels,” and the “new and magnificent church which was not finished when I visited it”—St. Mary Lateran. The refectory, which the Templars called the “palace,” was a huge Gothic structure, its vaulted roof supported by columns, its walls covered with trophies taken from the enemy: swords, helmets, painted shields, and gilded coats of mail. At mealtimes trestle tables were set up and spread with linen cloths; the flagstone floor was covered with rushes. Between the palace and the church stood the dormitories, corridors of monkish cells furnished with a chair or stool, a chest, and a bed with mattress, bolster, sheet, and blanket. The sergeants slept in a common room. The complex included an infirmary; individual houses for the officers; a “marshalsy” or armory where weapons, armor, and harness were kept and where mail and helmets were forged and horses shod; the draper’s establishment, where cloth was stored and clothing and shoes made; and the kitchens. Excavated into the rock were deep wells, and there were vast cellars for the storage of grain and fodder. Outside the city the Temple maintained cattle, horse, and sheep farms.

5

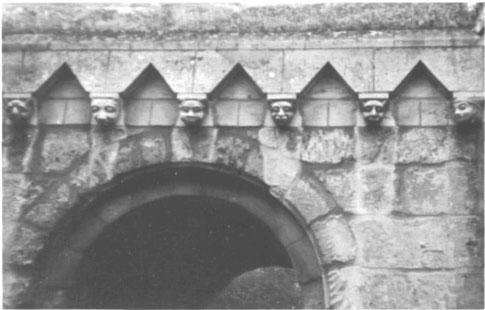

GROTESQUE HEADS DECORATE TEMPLE CHURCH, LAON

.

RUINS OF ROUND TEMPLE CHURCH, LANLEFF, BRITTANY

.

HOSPITALER CASTLE, LE POËT-LAVAL, PROVENCE

.

The Templar organization created an incessant traffic between Europe and the Holy Land, shipping gold, silver, cloth, armor, and horses to the East, whence returned brothers on missions to the West, sick or elderly knights on leave, visiting officers on tours of inspection. A stream of messengers traveled in both directions.

The total number of Knights Templars in the Holy Land at any one time was never large. Figures in the thousands given by the chroniclers for battles were typically exaggerated and included sergeants, vassals, mercenaries, and native auxiliaries called Turcopoles. The number of knights engaged in a single battle rarely exceeded four hundred. The total of Templars in Europe also was numbered in the hundreds, at most one or two thousand.

6

The extraordinary success of the Templars and St. Bernard’s promotion of the Order soon led to imitations. The Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem, founded before the First Crusade by merchants from Amalfi as a hospice for pilgrims, staffed by Benedictine monks, began during the Second Crusade (1146–1149) to take part in fighting. By the mid-twelfth century it had become a Military Order, while retaining its philanthropic character, and the dual role was formalized in 1206. Between 1164 and 1170 the Orders of Calatrava, Santiago, and Alcantara were established to fight the Moors in Spain and Portugal. A hospital set up in Acre by German merchants from Lübeck and Bremen in 1190, during the Third Crusade, adopted the Rule of the Hospitalers and was recognized as an independent order. In 1198 it was transformed into the Order of Teutonic Knights, which, however, did most of its fighting in Europe, in the Baltic region.

For a century and a half the defense of the Christian European bridgehead in Asia Minor was primarily in the hands of the garrisons of Templars, Hospitalers, and Teutonic Knights. But whenever a new Crusade was undertaken, the knights of the Orders were obliged to submit to the leadership, usually royal or imperial, of the expedition’s head. The arrangement did not always work smoothly. Men who spent their lives in the Holy Land often had a different perception of the military and political situation from the leaders of the Crusade and therefore favored a different strategy. More, their self-interest might diverge from that of Crusaders bent on achieving an immediate and perhaps chimerical objective. An ill-conceived Crusading operation might end by leaving the permanent garrison of the country worse off than it had been to start with. Crusaders returned home, but the Military Orders remained, a small Christian island in a stormy Muslim sea. Often, however, the superior experience of the Orders was recognized and deferred to. In 1148, in the Second Crusade, Louis VII of France prevailed upon his knights to place themselves under the orders of the Templar officers, who divided them into squadrons and trained them to endure attack without being drawn into pursuit, to attack only under orders, to rally to the main body of the army on signal, and to maintain a fixed order of march.

7

ENTRANCE GATE TO TEMPLAR COMMUNITY, RICHERENCHES, PROVENCE

.

VAULTED CHAMBER, PART OF THE INTERIOR OF THE TEMPLAR CASTLE OF CHASTEL BLANC.

(FROM

A HISTORY OF THE CRUSADES,

EDITED BY KENNETH M. SETTON, UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN PRESS)

The Orders were prominent in the Christian resistance against Saladin, the great sultan who united the Muslims in the last quarter of the twelfth century for a major Islamic offensive. Checked at Ascalon in 1177 and a year later at Jacob’s Ford on the northern frontier of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, Saladin gained a decisive victory at Hattin in 1187. Some two hundred Templar and Hospitaler prisoners, including the Masters of both Orders, were executed at Saladin’s command because they were “the firebrands of the Franks,” and “these more than all the other Franks destroy the Arab religion and slaughter us.”

8

Jerusalem fell at once, and the Third Crusade was organized in Europe in an attempt to recover it. When the Crusaders arrived, the Military Orders placed themselves formally under the command of Richard Lionheart, but actually they served as the English king’s chief advisers. Though the Crusade failed to recover Jerusalem, it established the Military Orders as major powers in Syria. Once again, the Crusaders, French, English, and German, went home, and the Templars and Hospitalers remained.

But unlike most of the handful of European settlers, with the exception of the Italian merchant colonies on the coast, they were backed by important resources in Europe, and Saladin and his successors had no easy time dislodging them. The most significant contribution the three great Orders made to the defense of the Holy Land was to build (or rebuild), maintain, and garrison the frontier castles.

9

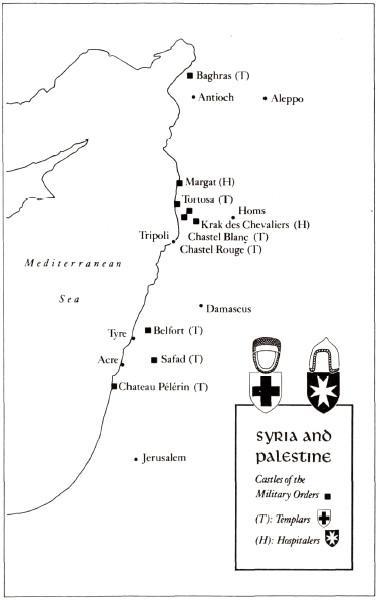

These massive masonry fortresses represented the full development of medieval military science. Only the Military Orders were rich and powerful enough to keep them constantly manned and in fighting trim. At most strategic points, strongholds, perhaps in ruins, already existed. These were taken over, enlarged, and given the most up-to-date elaboration. Where necessary, castles were built from scratch. The Templars’ largest fortress, the castle of Tortosa, in the county of Tripoli, was part of the defenses of the city of Tortosa, its concentric curtain walls overlooking the Mediterranean. It withstood Saladin’s attack in 1188. Second in importance, Chateau Pélérin (Pilgrim Castle) was built in 1218 with the aid of the Teutonic Knights on a rocky promontory south of Acre. Surrounded on three sides by the sea, it was protected toward the mainland by three lines of defense, a moat with a low wall, a second wall with three rectangular towers, and a bailey (courtyard) defended by two towers 110 feet high in a massive curtain wall. Chateau Pélérin was never taken by the Muslims. Other Templar castles included Safad, east of Acre, Belfort, Chastel Rouge, Chastel Blanc, Baghras, and La Roche Guillaume.

The most famous of all the Crusader castles was the Krak des Chevaliers, northeast of Tripoli. An Arab castle on the site was captured by the Crusaders in 1110. A vassal of the count of Tripoli occupied it until 1142, when the count ceded it to the Hospitalers, who built a huge concentric fortress, its two rings of massive walls dominated by great towers and separated by a wide moat. The Hospitalers’ other important castle, Margat, between Latakia and Tripoli, ceded to them by its baronial owner in 1186, was built on a mountain spur, with a double line of fortifications and a great circular tower that a thirteenth-century pilgrim described as seeming “to support the heavens, rather than exist for defense.”

10

Saladin found both the Krak des Chevaliers and Margat too strong to attack.