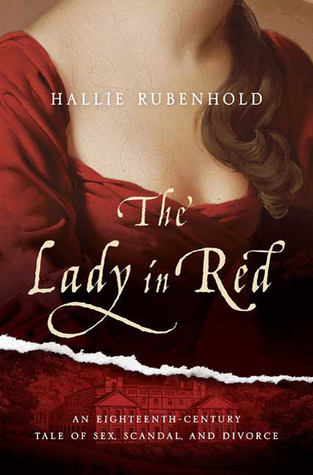

The Lady In Red: An Eighteenth-Century Tale Of Sex, Scandal, And Divorce

Read The Lady In Red: An Eighteenth-Century Tale Of Sex, Scandal, And Divorce Online

Authors: Hallie Rubenhold

Tags: #*Retail Copy*, #History, #Non-Fiction, #European History, #Biography

BOOK: The Lady In Red: An Eighteenth-Century Tale Of Sex, Scandal, And Divorce

13.2Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author´s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

For Frank

Table of Contents

Title Page

Introduction

1 -

The Heir of Appuldurcombe

2 -

A Girl Called Seymour

3 -

Sir Finical Whimsy and His Lady

4 -

Maurice George Bisset

5 -

A Coxheath Summer

6 -

A Plan

7 -

19th of November 1781

8 -

The Cuckold’s Reel

9 -

Retribution

10 -

The Royal Hotel, Pall Mall

11 -

A House of Spies

12 -

The World Turned Upside Down

13 -

‘Worse-than-sly’

14 -

‘Lady Worsley’s Seraglio’

15 -

The Verdict

16 -

‘The Value of a Privy Counsellor’s Matrimonial Honour’

17 -

‘The New Female Coterie’

18 -

Variety

19 -

Exile

20 -

The Dupe of Duns

21 -

Museum Worsleyanum

22 -

Repentance

23 -

A Deep Retirement

24 -

Mr Hummell and Lady Fleming

Also by

Acknowledgements

A Note on Eighteenth-Century Values and their Modern Conversions

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

Notes

Copyright Page

Introduction

1 -

The Heir of Appuldurcombe

2 -

A Girl Called Seymour

3 -

Sir Finical Whimsy and His Lady

4 -

Maurice George Bisset

5 -

A Coxheath Summer

6 -

A Plan

7 -

19th of November 1781

8 -

The Cuckold’s Reel

9 -

Retribution

10 -

The Royal Hotel, Pall Mall

11 -

A House of Spies

12 -

The World Turned Upside Down

13 -

‘Worse-than-sly’

14 -

‘Lady Worsley’s Seraglio’

15 -

The Verdict

16 -

‘The Value of a Privy Counsellor’s Matrimonial Honour’

17 -

‘The New Female Coterie’

18 -

Variety

19 -

Exile

20 -

The Dupe of Duns

21 -

Museum Worsleyanum

22 -

Repentance

23 -

A Deep Retirement

24 -

Mr Hummell and Lady Fleming

Also by

Acknowledgements

A Note on Eighteenth-Century Values and their Modern Conversions

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

Notes

Copyright Page

‘What do you know about Sir Richard and Lady Worsley of Appuldurcombe?’ I asked my taxi driver as our car rolled along the undulating road to Newport. I had just disembarked from the hovercraft at Ryde after gliding across the Solent from Portsmouth. The Isle of Wight, lingering off the coast of the English mainland has always held a reputation for its insularity and secrets. I was eager to learn if the secrets of the two subjects who had brought me there were retained in local memory. ‘Oh the Worsleys,’ said my driver, rumpling his brow. ‘There was some sort of trouble, wasn’t there? Some sort of scandal. Something bad’, he responded. It was an answer I received from almost everyone I quizzed on the island; hoteliers, parish priests, publicans and long-time residents. ‘The Worsleys?’ one man questioned with a hint of a snarl. ‘They were a bad family’. I was intrigued by the use of the word ‘bad’. No one seemed to know what precisely it was that made the Worsleys ‘bad’ or what ‘bad’ events had reduced their once imposing ancestral seat of Appuldurcombe to the ghostly shell that stands today.

I had come to Newport hoping to discover the story that lay behind one of the eighteenth century’s most sensational legal suits: the trial of Maurice George Bisset for criminal conversation with the wife of Sir Richard Worsley, an MP and Privy Counsellor. In February 1782, the case and its lurid sexual details made headline news. The country gossiped about it for months while the newspapers hounded and lampooned its protagonists for the better part

of their lives. Yet remarkably, a story that was as familiar to the inhabitants of the late eighteenth century as the Monica Lewinsky scandal is to living memory has virtually disappeared. All that seemed to remain on the Isle of Wight was a vague sense that disgrace clung to the family’s name.

of their lives. Yet remarkably, a story that was as familiar to the inhabitants of the late eighteenth century as the Monica Lewinsky scandal is to living memory has virtually disappeared. All that seemed to remain on the Isle of Wight was a vague sense that disgrace clung to the family’s name.

I was certain that within the archives of the island’s Record Office lay the answers to the many questions I had about the calamitous union of Sir Richard and Lady Seymour Dorothy Worsley. If I was to truly know the Worsleys and understand their legendary ‘badness’ I needed to read their own defences. I wished to hear what the Worsleys, now dead for nearly 200 years had to say and what explanations they might offer for their own failings. But as my days in the archive passed I realised that someone or perhaps even a number of people had beaten me to their correspondence.

The Georgians were astonishingly prolific people with pen and paper. As frequently as we send e-mails and make phone calls, they wrote letters. Literally tens of thousands of little notes and lengthy narratives might be penned in the course of an individual’s lifetime. Messengers and servants were constantly dispatched to post the latest missive filled with tattle, politics and information on the day’s events. Fortunately, the correspondence of a number of the era’s more illustrious families and noteworthy literary figures has been preserved. The Lennox sisters, the Duchess of Devonshire and Horace Walpole all captured the minutiae of daily life and the complexities of human experience. However, for all the sheets of writing paper we have managed to salvage we have lost many more. While a good deal of correspondence was disposed of by the recipient or simply forgotten and left to rot, still more was systematically destroyed by priggish descendants. Entire collections were thrown into the fire in the hope that their secrets would burn away. Usually the first letters committed to the pyre belonged to people who went against the grain, who broke with tradition or flouted the norms, the very voices that we now really want to hear.

What I discovered was that two lifetimes of private letters from Sir Richard and Lady Worsley to a vast assortment of friends and family had been all but eliminated. I was certain that it was more deliberate than haphazard. Nevertheless what I found fascinating was that in spite of all attempts to blot it out, their reputation in some form persisted, especially on the Isle of Wight.

Undoubtedly, that which has fanned the dying embers of legend has not been what remains in writing about the Worsleys of Appuldurcombe, as much as what remains in paint. It was Joshua Reynold’s iconic portrait of Lady Worsley that originally sent me on my quest. This image of a proud, strident woman in a blazing red riding habit with one firm hand set on her hip and the other gripping a riding crop excites as many gasps today as it did when Reynolds first exhibited it in 1780. It is a very public picture which frequently appears in print and at major exhibitions. When not travelling, it hangs quite prominently as one of the masterpieces at Harewood House. What I hadn’t appreciated until recently was that the artist had also created a companion piece of her husband. He too is depicted in full length and dressed in the red regimental uniform of the South Hampshire Militia which he commanded. The portraits were intended to be thought of as a pair, but due to the history of its sitters, never hung together. In this case, art has mimicked the life of its subjects perfectly. Just as they had positioned themselves roughly 225 years ago, Lady Worsley stands under the public gaze, attracting attention for her brazenness as ‘a scarlet woman’, while her husband remains hidden from view, sequestered in a private family collection.

Until now, no one has ever attempted to reconstruct the sordid history of Sir Richard and Lady Worsley and the star-crossed marriage which exploded and re-formed their lives. As they were among the first to harness the power of newspapers and publications to wage war against one another, their legal dispute might rightly be identified as one of the first celebrity divorce cases. A vast amount of contemporary gossip, journalism, pamphlets, and lampoons exists to help tell their story, as well as meticulous transcriptions of the criminal conversation trial which catapulted them into infamy. I was also able to unearth hundreds of pages of painstakingly recorded witness depositions from their ‘divorce’ proceedings which open the private recesses of their tale even further. The richness of detail contained in the testimonies of servants, hotel staff, friends and family not only offers a blow-by-blow account of events but even captures the facial expressions, conversation and emotional responses of those caught up in the drama. This fascinating collection of documents allows for an unusually vivid insight into the crucial week of 19th November 1781. Together, these materials tell a captivating historical tale of love, wealth, sex, class and privilege, even without a large cache of personal correspondence.

I cannot pretend to have unravelled all of the mysteries of the Worsleys’ dark and complex tale. There are many sides to this story and many angles from which to view it. Like an archaeologist piecing together an ancient mosaic I have laid out the fragments and it is for you to visualise the entire picture.

The Heir of Appuldurcombe

In the early morning hours of the 8th of October 1767, a small packet ship sailed out of the harbour at Calais and on to the white crested waves of the English Channel. In addition to a cargo of parcels and letters bound for Dover, the vessel was ferrying an introverted and slightly awkward sixteen-year-old by the name of Richard Worsley. The boy’s inquisitive mind and his pocket watch kept him occupied throughout the rough sea passage. As the hulk rolled and dipped with the swells he lost himself in the ticking seconds. By his calculations he and his family endured a crossing of precisely ‘three hours and five and thirty minutes’. He jotted a notation of this into the back of a journal alongside a table of measurements. In the course of their long journey from Naples to Dover the young man had charted with meticulous care the expanse of road they had travelled, converting the distances from the Italian and French standards into English mileage. They had, according to his reckoning, ‘been exactly absent two years, five months and twenty days’.

It had been on account of his father, Sir Thomas Worsley’s deteriorating health that the 6th baronet’s entire household were uprooted for a curative sojourn amid the orange trees and crumbling ruins of the warm Mediterranean. Two years earlier, on the 23rd of April 1765 his wife, the polished hostess Lady Betty Worsley, his seven-year-old daughter Henrietta and his son, Richard assumed their seats inside a carriage which would trundle across the pitted roads of Europe towards southern Italy. The historian Edward Gibbon,

a friend of Sir Thomas’s, had condemned the baronet’s ‘scheme’ as ‘a very bad one’. ‘Naples’, he warned, had ‘no advantage but those of climate and situation; and in point of expense and education for his children is the very last place in Italy I should have advised’. However, contrary to Gibbon’s fears, the journey which wound them through the valleys of France and over the Swiss Alps into Italy offered the Worsley children a scholastic diet far richer in experience than any provided by tutors in England.

a friend of Sir Thomas’s, had condemned the baronet’s ‘scheme’ as ‘a very bad one’. ‘Naples’, he warned, had ‘no advantage but those of climate and situation; and in point of expense and education for his children is the very last place in Italy I should have advised’. However, contrary to Gibbon’s fears, the journey which wound them through the valleys of France and over the Swiss Alps into Italy offered the Worsley children a scholastic diet far richer in experience than any provided by tutors in England.

In spite of his doubts, Gibbon recognised that Sir Thomas Worsley was an individual who valued knowledge, more so than many of his acquaintances. Although the historian marked him as ‘a man of entertainment’ he also admitted that he possessed ‘sense’ and an interest in antiquity. The library at Pylewell, his Hampshire estate held well-thumbed volumes of Cicero, Plato and Herodotus and bound illustrations of Roman temples and villas, many of which he and his wife had visited in the early years of their marriage. As a devoted traveller Sir Thomas believed that whilst such works offered a useful introduction to the classical world, a greater understanding of it could be gained from standing in the shadows of ancient monuments.

Before he and his family left for Italy, the baronet decided to remove his son from Winchester College, where after only a year’s enrolment, Richard had been dubbed ‘Dick Tardy’ because ‘he lagged so far behind’. As it was unusual for a gentleman to travel abroad with his wife, let alone with his children, a parent less concerned with his son’s academic welfare would have left him in the hands of his tutors. However, Sir Thomas felt compelled to take command of his son’s studies, to create his own programme of education and hire instructors that met his specific criteria. He was also determined to assume some of the burden of his heir’s education by exposing Richard to the art and architecture that lay on their route to Naples. He placed his son between the buttresses of cathedrals, in colonnades and under rotundas. He plunged him into the jewel boxes of Europe; the gilt-embellished interiors of Catholicism, the private gallery walls aching with the heavy adornment of Michelangelo, Caravaggio, Titian and Raphael. He supervised him as he trod the paving stones of the freshly excavated Roman towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum and sent him up the side of the still gurgling Vesuvius so that he ‘could walk upon the coolest part of the lava’. This wealth of spectacles was difficult for Sir Thomas’s son to digest. Although the baronet encouraged him to keep a travel diary, Richard was unable to put anything into it beyond notations of his father and his tutor’s discourses, indicating which paintings were ‘executed

in the highest taste’ and enumerating ‘the profusion of different marbles’ used in the Palazzo Farnese. Perhaps an indication of the domineering character of his father, the young Richard Worsley seemed hesitant to hold opinions of his own or to express them, even in the privacy of a travel journal.

in the highest taste’ and enumerating ‘the profusion of different marbles’ used in the Palazzo Farnese. Perhaps an indication of the domineering character of his father, the young Richard Worsley seemed hesitant to hold opinions of his own or to express them, even in the privacy of a travel journal.

When Sir Thomas took his son’s education in hand, there were many lessons which he intended to impart. The importance of duty, role and legacy were foremost among these. He taught his son that the world was a rational place, one that rotated around the principle of fixed truths. The baronet might have taken the watch from his pocket and opened its cover to the boy. The eighteenth-century mind often likened the workings of the era to a timepiece. Civilisation might operate on a smooth continuum only when each gear and cog ticked and turned as it should without question. Each object beneath the clock face had been designed for a purpose from which it would be unnatural to depart. Unlike the other notched circles that moved within, Richard Worsley would have been told that his function was exceptional, and that the other gears worked to ensure his existence. As the heir to his father’s title and an estate that generated an income of over £2,000 per annum, Sir Thomas’s son was a member of one of 630 families that made up the ranks of the aristocracy and gentry. What ensured his position of privilege over approximately 1.47 million other English families was the Worsleys’ possession of land.

1

1

Historically, only the ownership of property bought respect and influence. After the King and the royal family, those entitled to the greatest obeisance were the varying ranks of the aristocracy and gentry. Both Parliament and the judiciary served their interests. Neither politicians nor judges were much concerned with the travails of the average man or woman, and the recently fashionable concept of ‘liberty’ was a privilege savoured most by those whose estates sprawled the widest. The basic principles of this were explained to Richard Worsley as a young child. His tutors and father instructed him that the dark wood-panelled interiors of Pylewell, his home, and its 228 acres of field would one day pass into his care. But this estate would form only a small portion of his inheritance.

The family’s principal seat, Appuldurcombe lay on the southern part of the Isle of Wight outside Ventnor, though it is unlikely that Sir Thomas

took his son beyond its gates on more than a few occasions. In the middle of 11,578 acres of ‘rich soil and excellent pasturage’, surrounded by beech trees and ‘venerable oaks of uncommon magnitude’ sat an incomplete baroque manor house, mournful and abandoned. At the start of the century his relation, Sir James Worsley, had planned to construct a spacious, modern home but diminishing funds eventually slowed building to a standstill. Neither Sir Thomas nor the 5th baronet had demonstrated much interest in resuming the project, but to Richard, Appuldurcombe held great possibilities. From its windows he might one day look across the hillocks and troughs of his parkland and survey those farms, villages, orchards and fields that secured the Worsleys’ wealth and political influence on the island.

took his son beyond its gates on more than a few occasions. In the middle of 11,578 acres of ‘rich soil and excellent pasturage’, surrounded by beech trees and ‘venerable oaks of uncommon magnitude’ sat an incomplete baroque manor house, mournful and abandoned. At the start of the century his relation, Sir James Worsley, had planned to construct a spacious, modern home but diminishing funds eventually slowed building to a standstill. Neither Sir Thomas nor the 5th baronet had demonstrated much interest in resuming the project, but to Richard, Appuldurcombe held great possibilities. From its windows he might one day look across the hillocks and troughs of his parkland and survey those farms, villages, orchards and fields that secured the Worsleys’ wealth and political influence on the island.

Between the two estates of Appuldurcombe and Pylewell generations of Worsleys since the reign of Henry VIII had passed their lives. Many of Richard Worsley’s ancestors had slipped without remark through the fingers of history, while others, more noteworthy, had been captured on its pages. The stories of the Tudor courtier Sir James and the first baronet, Sir Richard, were recounted to him with pride. In their lifetimes, sumptuous banquets were spread across Appuldurcombe’s tables, marriages were contracted with some of the most powerful families in England, and his relations were favoured with places at the courts of Henry VIII and Queen Elizabeth. It was the preservation of their name and the legacy of their deeds with which he would one day be charged.

Sir Thomas approached his parental duties with seriousness. While many of his contemporaries relegated the care of their children to servants and tutors, Sir Thomas enjoyed the company of his son and regularly had Richard at his side on journeys to London or Newport. Although this type of affective parenting was coming into fashion by mid-century, many found the baronet’s constant influence on the boy worrying.

Since the early seventeenth century, the reputation of the Worsleys as a family who enjoyed access to the monarch’s ear had diminished. Preferring a quiet local existence as gentry, they had retreated to their estates and bowed out of the prestigious circles of power. By the time of Richard’s birth they were known simply as country squires; backward, uncouth and fierce supporters of the Tory party. Their prominence had long been forgotten. One anonymous scribe dismissed the family as ‘never having been remarkable for producing either heroes or conjurors’; rather, they were a stock whose ‘hereditary characteristics’ had a history of ‘association with vanity

and folly’. With his boisterous and colourful behaviour, no one promoted this image of the Worsleys more than Sir Thomas.

and folly’. With his boisterous and colourful behaviour, no one promoted this image of the Worsleys more than Sir Thomas.

The 6th baronet’s aspirations were not lofty ones. Unlike many of his ancestors, he had no desire to hear his voice echo through the halls of Westminster. He did not wish to command a ship or assist in the governance of Britain’s growing empire. His primary interests lay in Hampshire where he executed his occasional duties as Justice of the Peace for Lymington, listening to his tenants squabble over the ownership of a cow or the paternity of an illegitimate child. From 1759 his time was chiefly occupied in the command of the South Hampshire Militia, one of thirty-six battalions raised to protect Britain from the possibility of a French attack. These legions of what Horace Walpole called ‘demi-soldiers’ were considered ‘a thing of jest’ among the military establishment. Led by ‘country gentlemen and men of property’ who were ‘imbued with a … looseness of conduct’, the militias were never destined to wield their bayonets in any real combat; instead they existed as a type of home guard and were marched futilely from county town to barrack and back again for no discernible purpose.

As the Colonel of the South Hampshire Militia, Sir Thomas presided at these activities, both official and extracurricular. According to Edward Gibbon’s account of his commanding officer, the 6th baronet cut a clownish figure. ‘I know his faults and I can not help excusing them,’ he wrote somewhat apologetically. The baronet may have been a man who valued the classical lessons of stoicism and self-control but his outward personality betrayed no hint of this. Sir Thomas’s manner was distinctly ‘unintellectual’ and ‘rustic’. He was a man ‘fond of the table and of his bed’, Gibbon wrote. ‘Our conferences were marked by every stroke of the midnight and morning hours, and the same drum which invited him to rest often summoned me to the parade.’ Unreliable and fanciful, the baronet was better known for his musings on ‘sensible schemes he will never execute and schemes he will execute which are highly ridiculous’ than engaging in the practicalities of life.

Undoubtedly this behaviour was due in part to his severe dependence on the bottle. When Gibbon first encountered him in 1759 Sir Thomas was already an incorrigible alcoholic and it was through ‘his example’ that ‘the daily practice of hard and even excessive drinking’ was encouraged among the officers of the battalion. A significant amount of time was spent in ‘bucolic carousing’ or the pursuit of drunken antics, like the incident when

the inebriated Sir Thomas roused his friend, the equally intoxicated politician John Wilkes from his sleep and ‘made him drink a bottle of claret in bed’. Although hard drinking among men of the landed classes was widely accepted as a normal part of masculine behaviour, Gibbon suggests that even by the liberal standards of the era, Sir Thomas’s attachment to drink was immoderate. By 1762 he had begun to feel the effects of gout and possibly other alcohol-related disorders. In the hope that the therapeutic waters of Spa might cure him, he travelled to Belgium that summer. Upon his return, Gibbon commented that ‘Spa has done him a great deal of good, for he looks another man’, but the perceived improvement lasted only until the first glass was poured. ‘ … We kept bumperizing till after Roll-calling,’ Gibbon wrote ‘Sir Thomas assuring us with every fresh bottle how infinitely soberer he has grown.’

the inebriated Sir Thomas roused his friend, the equally intoxicated politician John Wilkes from his sleep and ‘made him drink a bottle of claret in bed’. Although hard drinking among men of the landed classes was widely accepted as a normal part of masculine behaviour, Gibbon suggests that even by the liberal standards of the era, Sir Thomas’s attachment to drink was immoderate. By 1762 he had begun to feel the effects of gout and possibly other alcohol-related disorders. In the hope that the therapeutic waters of Spa might cure him, he travelled to Belgium that summer. Upon his return, Gibbon commented that ‘Spa has done him a great deal of good, for he looks another man’, but the perceived improvement lasted only until the first glass was poured. ‘ … We kept bumperizing till after Roll-calling,’ Gibbon wrote ‘Sir Thomas assuring us with every fresh bottle how infinitely soberer he has grown.’

While the baronet’s drinking caused his relations and friends concern, his unpolished conduct and rural habits were a source of true humiliation. He felt no obligation to own a town residence in London, as was the practice among fashionable families. Eschewing the lavish suppers and card parties which would have established his name in the capital the baronet chose to live simply and when he had to visit town, he took a modest rented house. This error of judgement left a poor impression on his associates, who in an age of conspicuous consumption interpreted scantily furnished rooms and a sparsely laid table as the hallmarks of poverty or a coarse character. Gibbon was horrified by what he encountered at Sir Thomas’s London residence. The house he described as ‘a wretched one’ and while there he was served ‘a dinner suitable to it’. Having been offered so meagre a meal, the historian stayed to finish three pints before departing ‘to sup with Captain Crookshanks’, a proper host who provided him with ‘an elegant supper’ and a variety of wines. Embarrassed at having glimpsed such a striking example of the Worsleys’ lack of cultivation Gibbon marvelled how his friend, ‘a man of two thousand pounds a year’, could make such ‘a poor figure’ in London.

Sir Thomas’s insistence on maintaining a lifestyle of ‘great oeconomy’ did not suit the tastes of his wife, Lady Betty Worsley. As the daughter of the 5th Earl of Cork and Orrery, one of the eighteenth century’s most celebrated literary patrons, Lady Betty had enjoyed a position at the centre of cultural activity in London, Dublin and at her father’s estate in Somerset. The earl’s drawing rooms had been warmed by the witty conversation of Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, Dr Johnson and his friend, the accomplished actor

David Garrick. What hopes Lady Betty may have had of continuing her father’s tradition of arts patronage were quashed soon after marriage by the force of her husband’s personality. While her name and connections facilitated an entrée into the most elite circles, the ‘great contrast between the baronet and his wife’ did not go unmentioned behind fluttering fans. In her attempts to sidestep social disgrace, Lady Betty’s appearances in the capital became less frequent. She preferred to remain in Hampshire and reign as the mistress of Pylewell or to slip away to the continent where she and her husband passed several years of their marriage untouched by social obligation. It was only after Sir Thomas’s death in 1768 that Lady Betty re-established herself in London. Taking a town house on Dover Street, she made her home a centre for lively musical parties and artistic gatherings.

David Garrick. What hopes Lady Betty may have had of continuing her father’s tradition of arts patronage were quashed soon after marriage by the force of her husband’s personality. While her name and connections facilitated an entrée into the most elite circles, the ‘great contrast between the baronet and his wife’ did not go unmentioned behind fluttering fans. In her attempts to sidestep social disgrace, Lady Betty’s appearances in the capital became less frequent. She preferred to remain in Hampshire and reign as the mistress of Pylewell or to slip away to the continent where she and her husband passed several years of their marriage untouched by social obligation. It was only after Sir Thomas’s death in 1768 that Lady Betty re-established herself in London. Taking a town house on Dover Street, she made her home a centre for lively musical parties and artistic gatherings.

Other books

The Manor by Scott Nicholson

BREATHE: A Billionaire Romance, Part 3 by Jenn Marlow

Kaleb (Samuel's Pride Series) by Barton, Kathi S.

The Witch Collector Part II by Loretta Nyhan

To Russia With Love (Countermeasure Series) by Aubrey, Cecilia, Almeida, Chris

The Gunfighter and The Gear-Head by Cassandra Duffy

The Rights Revolution by Michael Ignatieff

Forbidden Passion by Herron, Rita

Daughter of Ancients by Carol Berg

Death to Tyrants! by Teegarden, David