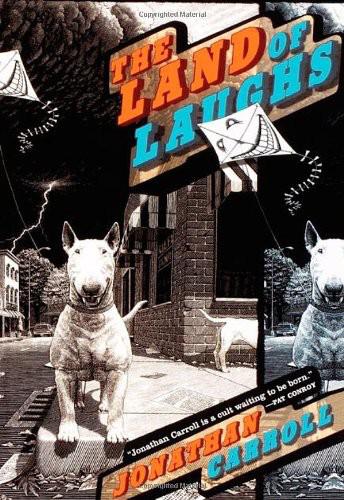

The Land of Laughs

Read The Land of Laughs Online

Authors: Jonathan Carroll

Tags: #General, #Fantasy, #Fiction, #Horror, #Horror Fiction, #Biographers, #Children's Stories, #Biography as a Literary Form, #Missouri, #Authorship, #Children's Stories - Authorship

THE LAND OF LAUGHS

by Jonathan Carroll

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this novel are either fictitious or are used fictitiously.

THE LAND OF LAUGHS

Copyright (c) 1980 by Jonathan Carroll

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or portions thereof, in any form.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

First published in Great Britain by Hamlyn Paperbacks, 1982.

An Orb Edition

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, LLC

New York, NY 10010

www.tor.com

Design by Heidi M. G. Eriksen

ISBN 0-312-87311-5 (alk. paper)

First Orb Edition: February 2001

For June, who is the best of all New Faces,

and for Beverly — The Queen of All

Be regular and orderly in your life like a

bourgeois, so that you may be violent and

original in your work.

— Flaubert

1

“Look, Thomas, I know you’ve probably been asked this question a million times before, but what was it really like to be Stephen Abbey’s —”

“— Son?” Ah, the eternal question. I recently told my mother that my name isn’t Thomas Abbey, but rather Stephen Abbey’s Son. This time I sighed and pushed what was left of my cheesecake around the plate. “It’s very hard to say. I just remember him as being very friendly, very loving. Maybe he was just stoned all the time.”

Her eyes lit up at that. I could almost hear the sharp little wheels clickety-clicking in her head. So he

was

an addict! And it came straight from his kid’s mouth. She tried to cover her delight by being understanding and giving me a way out if I wanted it.

“I guess, like everyone else, I’ve always read a lot about him. But you never know if those articles are true or not, you know?”

I didn’t feel like talking about it anymore. “Most of the stories about him are probably pretty true. The ones I’ve heard about or read are.” Luckily the waitress was passing, so I was able to make a big thing out of getting the bill, looking it over, paying it — anything to stop the conversation.

When we got outside, December was still there and the cold air smelled chemical, like a refinery or a tenth-grade chemistry class deep into the secrets of stink. She slipped her arm through mine. I looked at her and smiled. She was pretty — short red hair, green eyes that were always wide with a kind of happy astonishment, a nice body. So I couldn’t help smiling then too, and for the first time that night I was glad she was there with me.

The walk from the restaurant to the school was just a little under two miles, but she insisted on our hiking it both ways. Over would build up our appetites, back would work off what we’d eaten. When I asked her if she chopped her own wood, she didn’t even crack a smile. My sense of humor has often been lost on people.

By the time we got back to the school we were pretty chummy. She hadn’t asked any more questions about my old man and had spent most of the time telling me a funny story about her gay uncle in Florida.

We got back to Founder’s Hall, a masterpiece of neo-Nazi architecture, and I saw that I had stopped us on the school crest laid into the floor. Her arm tightened in mine when she noticed this, and I thought I might as well ask then as anytime.

“Would you like to see my masks?”

She giggled a giggle that sounded like water draining from a sink. Then she shook her finger at me in a no-no-naughty-boy! way.

“You don’t mean your etchings, do you?”

I had hoped that she might he half-human, but this dirty little Betty Boop routine popped that balloon. Why couldn’t a woman be marvelous for once? Not winky, not liberated, not vacuous …

“No, really, you see, I have this mask collection, and —”

She squeezed me again and cut off the circulation in my upper arm.

“I’m just kidding, Thomas. I’d love to see it.”

Like all tight-fisted New England prep schools, the apartments that they gave their teachers, especially single teachers, were awful. Mine had a tiny hallway, a study that was painted yellow once but forgot, a bedroom, and a kitchen so old and fragile that I never once thought of cooking there because I had to pay all of the repair costs.

But I had sprung for a gallon of some top-of-the-line house paint so that at least the wall that the collection was on would have a little dignity.

The only outside door to the place opened onto the hallway, so coming in with her was okay. I was nervous, but I was dying to see how she’d react. She was cuddling and cooing the whole time, but then we went around the corner into my bed-living room.

“Oh, my

God!

Wha … ? Where did you get … ?” Her voice trailed off into little puffs of smoke as she went up to take a closer look. “Where did you get, uh, him?”

“In Austria. Isn’t it a great one?” Rudy the Farmer was brown and tan and beautifully carved in an almost offhand way that added to his rough, piggy-fat, drunken face. He gleamed too, because I had been experimenting that morning with a new kind of linseed oil that hadn’t dried yet.

“But it’s … it’s almost real. He’s shining!”

At that point my hopes went up up up. Was she awed? If so, I’d forgive her. Not many people had been awed by the masks. They got many points from me when they were.

I didn’t mind when she reached out to touch some of them as she moved on. I even liked her choice of which ones to touch. The Water Buffalo, Pierrot, the

Krampus

.

“I started buying them when I was in college. When my father died, he left me some money, so I took a trip to Europe.” I went over to the Marquesa and touched her pink-peach chin softly. “This one, the Marquesa, I saw in a little side-street store in Madrid. She was the first one I bought.”

My Marquesa with her tortoiseshell combs, her too-white and too-big teeth that had been smiling at me for almost eight years. The Marquesa.

“And what’s that one?”

“That’s a death mask of John Keats.”

“A death mask?”

“Yes. Sometimes when famous people die, they’ll make a mold of their faces before they bury them. Then they cast copies …” I stopped talking when she looked at me as if I were Charles Manson.

“But they’re just so

creepy!

How can you sleep in here with them? Don’t they scare you?”

“No more than you do, my dear.”

That was that. Five minutes later she was gone and I was putting some of the linseed oil on another mask.

My father used to say whenever he finished making a movie that he’d never do it again as long as he lived. But like most of the other things he said, it was bullshit, because after a few weeks of rest and a fat deal cooked up for him by his agent, he’d go back under the lights for a forty-third triumphant return.

After four years of teaching I was saying the same thing. I had had my fill of grading papers, faculty meetings, and coaching ninth-grade intramural basketball. There was enough money from my inheritance to do what I wanted, but to he honest, I had no real idea of what to do instead. Correction: I had a very specific idea, but it was a pipe dream. I wasn’t a writer, I didn’t know the first thing about doing research, and I hadn’t even read all the things that he’d written — not that there were that many of them.

My dream was to write a biography of Marshall France, the very mysterious, very wonderful author of the greatest children’s books in the world. Books like

The Land of Laughs

and

The Pool of Stars

that had helped me to keep my sanity on and off throughout my thirty years.

That was the one wonderful thing that my father did for me. On my ninth birthday — momentous day! — he gave me a little red car with a real engine in it that I instantly hated, a baseball that was signed “From Your Daddy’s Number One Fan, Mickey Mantle,” and as an afterthought I’m sure, the Shaver-Lambert edition of

The Land of Laughs

with the Van Walt illustrations. I still have it.

I sat in the car because I knew that was what my father wanted me to do and read the book from cover to cover for the first time. When I refused to put it down after a year, my mother threatened to call Dr. Kintner, my hundred-dollar-a-minute analyst, and tell him that I wasn’t “cooperating.” As always in those days, I ignored her and turned the page.

“The Land of Laughs was lit by eyes that saw the lights that no one’s seen.”

I expected everyone in the world to know that line. I sang it constantly to myself in that low intimate voice that children use to talksing to themselves when they’re alone and happy.

Since I never had any need for pink bunnies or stuffed doggies to ward off night spooks or kid gobblers, my mother finally allowed me to carry the book around with me. I think she was hurt because I never asked her to read it to me. But by then I was so selfish about

The Land of Laughs

that I didn’t even want to share it with someone else’s voice.

I secretly wrote France a letter, the only fan letter I’ve ever written, and was ecstatic when he wrote back.

Dear Thomas,

The eyes that light The Land of Laughs

See you and wink their thanks.

Your friend,

Marshall France

I had the letter framed when I was in prep school and still looked at it when I needed a shot of peace of mind. The handwriting was a kind of spidery italic with the Y’s and the G’s dropping far below the line, and many of the letters of the words weren’t connected. The envelope was postmarked Galen, Missouri, which is where France lived for most of his life.

I knew little things like that about him. I couldn’t resist some amateur sleuthing. He died of a heart attack at forty-four, was married, and had a daughter named Anna. He hated publicity, and after the success of his book

The Green Dog’s Sorrow

, he pretty much disappeared from the face of the earth. A magazine did an article on him that had a picture of his house in Galen. It was one of those great old Victorian monsters that had been plopped down on an average little street in the middle of Middle America. Whenever I saw houses like that, I remembered my father’s movie where the guy came home from the war, only to be killed by cancer at the end. Since most of the action seemed to take place in the living room and on the front porch, my father called the movie

Cancer House

. It made a fortune and be was nominated for another Oscar.

In February, the month when suicide always looks good to me, I taught a class in Poe that helped me to decide at least to apply for a leave of absence for the following fall before something dangerous happened to my brain. A normal lunkhead named Davis Bell was supposed to give a report to the class on “The Fall of the House of Usher.” He got up in front of us and said this. I quote. ” ‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ by Edgar Allan Poe, who was an alcoholic and married his younger cousin.”

I

had told them all that several days before in hopes of stimulating their curiosity. To continue. “… married his younger cousin. This house, or I mean this story, is about this house of ushers …”

“Who fall?” I prompted him, at the risk of giving the plot away to his classmates, who hadn’t read the story either.

“Yeah, who fall.”

Time to leave.

Grantham gave me the news that my application had been approved. As always, smelling of coffee and farts, he hung his arm across my shoulder, and pushing me toward the door, asked what I was going to do with my “little vacation.”

“I was thinking of writing a book.” I didn’t look at him because I was afraid his expression would be the same I’d have if someone like me had just said that he was going to write a book.

“That’s great, Tom! A biography of your dad, maybe?” He put a finger to his bps and looked dramatically from side to side as if the walls were listening. “Don’t worry about me. I won’t tell a soul, I promise. Those things are very in these days, you know. What it was really like on the inside, and all that. Don’t forget, though, that I’ll want an autographed copy when it comes out.”

It was really time to leave.

The rest of the winter trimester passed quickly, and Easter break came almost too soon. Over the holiday I was tempted to back out of the whole thing several times, because leaping into the unknown with a project I didn’t even know how to begin, much less complete, was not at all inspiring. But they’d hired my replacement, I’d bought a new little station wagon for the trip out to Galen, and the students certainly weren’t pulling on my coattails to stay. So I thought that no matter what happened, getting away from the likes of Davis Bell and Farts Grantham would do me good.

Then some strange things happened.

I was browsing through a rare-book store one afternoon when I saw on the sales desk the Alexa edition of France’s

Peach Shadows

with the original Van Walt illustrations. The book had been out of print for years for some reason, and I hadn’t read it.