The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language (69 page)

Read The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Those who have been persuaded to think well of my design, require that it should fix our language, and put a stop to those alterations which time and chance have hitherto been suffered to make in it without opposition. With this consequence I will confess that I have flattered myself for a while; but now begin to fear that I have indulged expectations which neither reason nor experience can justify. When we see men grow old and die at a certain time one after another, from century to century, we laugh at the elixir that promises to prolong life to a thousand years; and with equal justice may the lexicographer be derided, who being able to produce no example of a nation that has preserved their words and phrases from mutability, shall imagine that his dictionary can embalm his language, and secure it from corruption and decay, that it is in his power to change sublunary nature, and clear the world at once from folly, vanity, and affectation. With this hope, however, academies have been instituted, to guard the avenues of their languages, to retain fugitives, and to repulse intruders; but their vigilance and activity have hitherto been vain; sounds are too volatile and subtle for legal restraints; to enchain syllables, and to lash the wind, are equally the undertakings of pride, unwilling to measure its desires by its strength.

Early in this book I asked why you should believe that there is a language

instinct. Now that I have done my best to convince you that there is one, it is time to ask why you should care. Having a language, of course, is part of what it means to be human, so it is natural to be curious. But having hands that are not occupied in locomotion is even more important to being human, and chances are you would never have made it to the last chapter of a book about the human hand. People are more than curious about language; they are passionate. The reason is obvious. Language is the most accessible part of the mind. People want to know about language because they hope this knowledge will lead to insight about human nature.

This tie-in animates linguistic research, raising the stakes in arcane technical disagreements and attracting the attention of scholars from far-flung disciplines. Jerry Fodor, the philosopher and experimental psycholinguist, studies whether sentence parsing is an encapsulated mental module or blends in with general intelligence, and he is more honest than most in discussing his interest in the controversy:

“But look,” you might ask, “why do you care about modules so much? You’ve got tenure; why don’t you take off and go sailing?” This is a perfectly reasonable question and one that I often ask myself…. Roughly, the idea that cognition saturates perception belongs with (and is, indeed, historically connected with) the idea in the philosophy of science that one’s observations are comprehensively determined by one’s theories; with the idea in anthropology that one’s values are comprehensively determined by one’s culture; with the idea in sociology that one’s epistemic commitments, including especially one’s science, are comprehensively determined by one’s class affiliations; and with the idea in linguistics that one’s metaphysics is comprehensively determined by one’s syntax [i.e., the Whorfian hypothesis—SP]. All these ideas imply a kind of relativistic holism: because perception is saturated by cognition, observation by theory, values by culture, science by class, and metaphysics by language, rational criticism of scientific theories, ethical values, metaphysical world-views, or whatever can take place only

within

the framework of assumptions that—as a matter of geographical, historical, or sociological accident—the interlocutors happen to share. What you can’t do is rationally criticize the framework.

The thing is: I

hate

relativism. I hate relativism more than I hate anything else, excepting, maybe, fiberglass powerboats. More to the point, I think that relativism is very probably false. What it overlooks, to put it briefly and crudely, is the fixed structure of human nature. (That is not, of course, a novel insight; on the contrary, the

malleability

of human nature is a doctrine that relativists are invariably much inclined to stress; see, for example, John Dewey….) Well, in cognitive psychology the claim that there is a fixed structure of human nature traditionally takes the form of an insistence on the heterogeneity of cognitive mechanisms and the rigidity of the cognitive architecture that effects their encapsulation. If there are faculties and modules, then not everything affects everything else; not everything is plastic. Whatever the All is, at least there is more than One of it.

For Fodor, a sentence perception module that delivers the speaker’s message verbatim, undistorted by the listener’s biases and expectations, is emblematic of a universally structured human mind, the same in all places and times, that would allow people to agree on what is just and true as a matter of objective reality rather than of taste, custom, and self-interest. It is a bit of a stretch, but no one can deny that there is a connection. Modern intellectual life is suffused with a relativism that denies that there is such a thing as a universal human nature, and the existence of a language instinct in any form challenges that denial.

The doctrine underlying that relativism, the Standard Social Science Model (SSSM), began to dominate intellectual life in the 1920s. It was a fusion of an idea from anthropology and an idea from psychology.

Whereas animals are rigidly controlled by their biology, human behavior is determined by culture, an autonomous system of symbols and values. Free from biological constraints, cultures can vary from one another arbitrarily and without limit.

Human infants are born with nothing more than a few reflexes and an ability to learn. Learning is a general-purpose process, used in all domains of knowledge. Children learn their culture through indoctrination, reward and punishment, and role models.

The SSSM has not only been the foundation of the study of humankind within the academy, but serves as the secular ideology of our age, the position on human nature that any decent person should hold. The alternative, sometimes called “biological determinism,” is said to assign people to fixed slots in the socio-political-economic hierarchy, and to be the cause of many of the horrors of recent centuries: slavery, colonialism, racial and ethnic discrimination, economic and social castes, forced sterilization, sexism, genocide. Two of the most famous founders of the SSSM, the anthropologist Margaret Mead and the psychologist John Watson, clearly had these social implications in mind:

We are forced to conclude that human nature is almost unbelievably malleable, responding accurately and contrastingly to contrasting cultural conditions…. The members of either or both sexes may, with more or less success in the case of different individuals, be educated to approximate [any temperament]…. If we are to achieve a richer culture, rich in contrasting values, we must recognize the whole gamut of human potentialities, and so weave a less arbitrary social fabric, one in which each diverse human gift will find a fitting place. [Mead, 1935]

Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I’ll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select—doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief, and yes, even beggarman and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors. [Watson, 1925]

At least in the rhetoric of the educated, the SSSM has attained total victory. In polite intellectual conversations and respectable journalism, any generalization about human behavior is carefully prefaced with SSSM shibboleths that distance the speaker from history’s distasteful hereditarians, from medieval kings to Archie Bunker. “Our society,” the discussions begin, even if no other society has been examined. “Socializes us,” they continue, even if the experiences of the child are never considered. “To the role…” they conclude, regardless of the aptness of the metaphor of “role,” a character or part arbitrarily assigned to be played by a performer.

Very recently, the newsmagazines tell us that “the pendulum is swinging back.” As they describe the appalled pacifist feminist parents of a three-year-old gun nut son and a four-year-old Barbie-doll-obsessed daughter, they remind the reader that hereditary factors cannot be ignored and that all behavior is an interaction between nature and nurture, whose contributions are as inseparable as the length and width of a rectangle in determining its area.

I would be depressed if what we have learned about the language instinct were folded into the mindless dichotomies of heredity-environment (a.k.a. nature-nurture, nativism-empiricism, innate-acquired, biology-culture), the unhelpful bromides about inextricably intertwined interactions, or the cynical image of a swaying pendulum of scientific fashion. I think that our understanding of language offers a more satisfying way of studying the human mind and human nature.

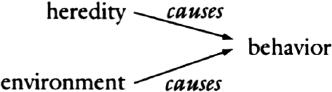

To begin with, we can discard the pre-scientific, magical model in which the issues are usually framed:

The “controversy” over whether heredity, environment, or some interaction between the two causes behavior is just incoherent. The organism has vanished; there is an environment without someone to perceive it, behavior without a behaver, learning without a learner. As Alice thought to herself when the Cheshire Cat vanished quite slowly, ending with the grin which remained some time after the rest of it had gone: “Well! I’ve often seen a cat without a grin, but a grin without a cat! It’s the most curious thing I ever saw in all my life!”

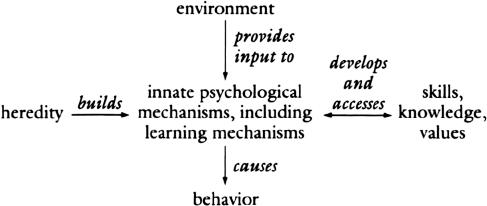

The following model is also simplistic, but it is a much better beginning:

For we can now do justice to the complexity of the human brain, the immediate cause of all perception, learning, and behavior. Learning is not an alternative to innateness; without an innate mechanism to do the learning, it could not happen at all. The insights we have gained about the language instinct make this clear.

First, to reassure the nervous: yes, there are important roles for both heredity and environment. A child brought up in Japan ends up speaking Japanese; the same child, if brought up in the United States, would end up speaking English. So we know that the environment plays a role. If a child is inseparable from a pet hamster when growing up, the child ends up speaking a language, but the hamster, exposed to the same environment, does not. So we know that heredity plays a role. But there is much more to say.

• Since people can understand and speak an infinite number of novel sentences, it makes no sense to try to characterize their “behavior” directly—no two people’s language behavior is the same, and a person’s potential behavior cannot even be listed. But an infinite number of sentences can be generated by a finite rule system, a grammar, and it does make sense to study the mental grammar and other psychological mechanisms underlying language behavior.

• Language comes so naturally to us that we tend to be blasé about it, like urban children who think that milk just comes from a truck. But a close-up examination of what it takes to put words together into ordinary sentences reveals that mental language mechanisms must have a complex design, with many interacting parts.

• Under this microscope, the babel of languages no longer appear to vary in arbitrary ways and without limit. One now sees a common design to the machinery underlying the world’s language, a Universal Grammar.

• Unless this basic design is built in to the mechanism that learns a particular grammar, learning would be impossible. There are many possible ways of generalizing from parents’ speech to the language as a whole, and children home in on the right ones, fast.

• Finally, some of the learning mechanisms appear to be designed for language itself, not for culture and symbolic behavior in general. We have seen Stone Age people with high-tech grammars, helpless toddlers who are competent grammarians, and linguistic idiot savants. We have seen a logic of grammar that cuts across the logic of common sense: the

it

of

It is raining

that behaves like the

John

of

John is running

, the

mice-eaters

who eat

mice

differing from the

rat-eaters

who eat

rats

.

The lessons of language have not been lost on the sciences of the rest of the mind. An alternative to the Standard Social Science Model has emerged, with roots in Darwin and William James and with inspiration from the research on language by Chomsky and the psychologists and linguists in his wake. It has been applied to visual perception by the computational neuroscientist David Marr and the psychologist Roger Shepard, and has been elaborated by the anthropologists Dan Sperber, Donald Symons, and John Tooby, the linguist Ray Jackendoff, the neuroscientist Michael Gazzaniga, and the psychologists Leda Cosmides, Randy Gallistel, Frank Keil, and Paul Rozin. Tooby and Cosmides, in their important recent essay “The Psychological Foundations of Culture,” call it the Integrated Causal Model, because it seeks to explain how evolution caused the emergence of a brain, which causes psychological processes like knowing and learning, which cause the acquisition of the values and knowledge that make up a person’s culture. It thus integrates psychology and anthropology into the rest of the natural sciences, especially neuroscience and evolutionary biology. Because of this last connection, they also call it Evolutionary Psychology.