The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn (42 page)

Read The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn Online

Authors: Nathaniel Philbrick

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century

At Bradley’s suggestion, the Crow scout Little Face was placed at the head of the column, and in a few hours’ time, they were camped about a mile and a half from the Little Bighorn. At daylight on June 26, Lieutenant Bradley and his Crow scouts were sent out to investigate the trail ahead. They found evidence that four unshod Indian ponies had recently passed by on their way to the Bighorn. They soon discovered that the ponies belonged to three of Custer’s Crow scouts, White Man Runs Him, Hairy Moccasin, and Goes Ahead, who had already crossed over to the west bank of the Bighorn. After communicating with the scouts, Little Face rode back to Bradley.

For awhile he could not speak [Bradley wrote], but at last composed himself and told his story in a choking voice, broken with frequent sobs. As he proceeded, the Crows one by one broke off from the group of listeners and going aside a little distance sat down alone, weeping and chanting that dreadful mourning song, and rocking their bodies to and fro. They were the first listeners to the horrid story of the Custer massacre, and outside of the relatives and personal friends of the fallen, there were none in this whole horrified nation of forty millions of people to whom the tidings brought greater grief.

This was the first word of the disaster to reach anyone associated with the Montana Column. Bradley personally delivered the message to Terry and his staff. “The story was sneered at,” Bradley wrote; “such a catastrophe it was asserted was wholly improbable, nay impossible.” Terry, Bradley noticed, “took no part in these criticisms, but sat on his horse silent and thoughtful, biting his lower lip.”

They proceeded and were soon in the valley of the Little Bighorn. About fifteen to twenty miles to the southeast was a cloud of dense smoke.

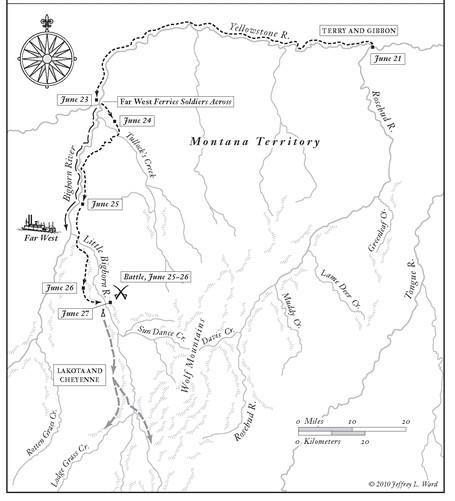

—THE MARCH OF THE MONTANA COLUMN TO THE LITTLE BIGHNORN,

June 21-27, 1876

—

As the majority of the column marched up the valley, Lieutenant Charles Roe led several cavalry companies to the bluffs paralleling the river to the right. From his elevated position Roe could see “a long line of moving dark objects defiling across the prairie from the Little Bighorn . . . as if the village were in motion, retreating before us.” Roe also saw some horsemen “clothed in blue uniforms . . . breaking into column and otherwise maneuvering like a body of cavalry.” Thinking they were from Custer’s regiment, he sent a detail to investigate. As they’d done earlier in the day on Reno Hill, the blue-clad warriors fired on the approaching soldiers, who were “quickly undeceived as to their character.”

As it was almost completely dark, Terry ordered the column to camp for the night. “Notwithstanding the disclosures of the day,” Terry’s staff remained confident “that there was not an Indian in our front and that the men seen were members of Custer’s command.” The Crow scouts knew better and had long since slipped away from the column and headed back to their reservation.

On the morning of June 27, five days after Custer had first set forth up the Rosebud River, the Montana Column resumed its march along the west bank of the Little Bighorn. Two advance guards led them up the valley while Terry and Gibbon remained with the slower-moving infantry. After passing a large, heavily wooded bend in the river, they caught a glimpse of two Indian tepees “standing in the open valley.” While Bradley’s advance guard of mounted infantry crossed the river to scout the hills to the east, the rest of the column marched into the abandoned village: a three-mile swath of naked tepee poles, discarded kettles, and other implements. Each of the two standing lodges was encircled by a ring of dead ponies and contained the corpses of several warriors. Among the debris they found the bloody underwear of Lieutenant James Sturgis, son of the Seventh Cavalry’s highest-ranking officer, Colonel Samuel Sturgis. There was also the buckskin shirt owned by Lieutenant James Porter. Judging from the bullet hole in the shirt, Porter had been shot near the heart.

Up ahead to the south, on the other side of the river, Gibbon could see what looked to be a crowd of people standing on a prominent hill. But were they soldiers or warriors? “The feeling of anxiety was overwhelming,” he wrote. By this time, Lieutenant Bradley had descended from the much closer hills almost directly across the river to the east. He rode up to Gibson and Terry. “I have a very sad report to make,” he said. “I have counted one hundred and ninety-seven dead bodies lying in the hills.”

“White men?” someone asked.

“Yes, white men.”

“There could be no question now,” Gibbon wrote. “The Crows were right.”

N

ot long afterward, Terry and Gibbon learned from Lieutenants Hare and Wallace that Major Reno and seven companies of the Seventh Cavalry were the men they’d seen watching from the hills. As Gibbon looked for a place to camp in the valley, Terry and his staff followed Hare and Wallace to the bluff.

Terry was openly weeping by the time he reached Reno’s battalion. Standing beside the major was Frederick Benteen. Almost immediately the captain asked whether Terry “knew where Custer had gone.”

“To the best of my knowledge and belief,” Terry replied, “he lies on this ridge about 4 miles below here with all of his command killed.”

“I can hardly believe it,” Benteen said. “I think he is somewhere down the Big Horn grazing his horses.” Benteen then launched into the refrain he’d been repeating ever since he arrived on Reno Hill: “At the Battle of the Washita he went off and left part of his command, and I think he would do it again.”

Terry was well aware of the history between Custer and Benteen. “I think you are mistaken,” he responded, “and you will take your company and go down where the dead are lying and investigate for yourself.”

P

rivate Jacob Adams was the the one who found Custer. He called to Benteen, who dismounted and walked over to have a closer look.

“By God,” he said, “that is him.”

CHAPTER 15

The Last Stand

D

uring his inspection of the battlefield, Benteen decided that there was no pattern to how the more than two hundred bodies of Custer’s battalion were positioned. “I arrived at the conclusion then that I have now,” he testified two and a half years later, “that it was a rout, a panic, till the last man was killed. There was no line on the battlefield; you can take a handful of corn and scatter it over the floor and make just such lines.” Today many of the descendants of the warriors who fought in the battle believe the rout started at the river.

According to these Native accounts, Custer’s portion of the battle began with a charge down Medicine Tail Coulee to the Little Bighorn. The troopers had started to cross the river when the warriors concealed on the west bank opened fire. The grandmother of Sylvester Knows Gun, a northern Cheyenne, was there. The troopers were led, she told her grandson, by an officer in a buckskin coat, and he was “the first one to get hit.” As the officer slumped in his saddle, three soldiers quickly converged around the horse of their wounded leader. “They got one on each side of him,” she said, “and the other one got in front of him, and grabbed the horse’s reins . . . , and they quickly turned around and went back across the river.” Sylvester Knows Gun maintained that this was Custer and that he was dead by the time he reached Last Stand Hill.

The wounding, if not death, of Custer at the early stages of the battle would explain much. Suddenly leaderless, the battalion dissolved in panic. According to Sylvester Knows Gun, the battle was over in just twenty minutes.

There is evidence, however, that Custer was very much alive by the time he reached Last Stand Hill. Unlike almost all the other weapons fired that day, Custer’s Remington sporting rifle used brass instead of copper cartridge casings, and a pile of these distinctive casings was found near his body. There is also evidence that Custer’s battalion, instead of being on the defensive almost from the start, remained on the offensive for almost two hours before it succumbed to the rapid disintegration described by Sylvester Knows Gun and others.

It may very well be that the warriors’ descendants have it right. But given the evidence found on and in the ground, along with the recorded testimony of many of the battle participants, it seems likely that Custer lived long enough to try to repeat his success at the Washita by capturing the village’s women and children. What follows is a necessarily speculative account of how this desperate attempt to secure hostages ultimately led to Custer’s Last Stand.

R

uns the Enemy had just helped drive Reno’s battalion across the river on the afternoon of June 25. He was returning to the village when he saw two Indians up on the ridge to the right, each one waving a blanket. They were shouting, he remembered, that “the genuine stuff was coming.”

He immediately crossed the river and rode to the top of the hill. He couldn’t believe what he saw: troopers, many more troopers than he and the others had just chased to the bluffs behind them. “They seemed to fill the whole hill,” he said. “It looked as if there were thousands of them, and I thought we would surely be beaten.” In the valley to the north, in precisely the same direction the troopers were riding, were thousands of noncombatants, some of them moving down the river toward a hollow beside a small creek, others gathered at the edge of the hills to the west, but all within easy reach of a swiftly moving regiment of cavalry. While Runs the Enemy and the others had been battling the first group of soldiers, this other, larger group of washichus had found a way around them and were now about to capture their women and children.

He rushed down to the encampment where the Lakota warriors returning from the battle with Reno’s battalion had started to gather. “I looked into their eyes,” he remembered, “and they looked different—they were filled with fear.” At that moment Sitting Bull appeared. Riding a buckskin horse back and forth, he addressed the warriors along the river’s edge. “A bird, when it is on its nest, spreads its wings to cover the nest and eggs and protect them,” Sitting Bull said. “It cannot use its wings for defense, but it can cackle and try to drive away the enemy. We are here to protect our wives and children, and we must not let the soldiers get them. Make a brave fight!”

As the warriors splashed across the river and climbed into the hills, Sitting Bull and his nephew One Bull headed down the valley. They must prepare the women and children to move quickly. As Sitting Bull admitted to a newspaper reporter a year and a half later, “[W]e thought we were whipped.”

I

n the vicinity of a hill topped by a circular hollow that was later named for his brother-in-law Lieutenant James Calhoun, Custer convened his final conference with the officers of his battalion. The Left Wing had just returned from its trip to the river. The Right Wing had marched up from a ridge to the south where it had been waiting for the imminent arrival of Frederick Benteen. The white-haired captain and his battalion were still nowhere in sight, but Custer could take solace in knowing that even though Benteen had dawdled at the Washita, he had come through splendidly in the end.