The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat (39 page)

Read The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat Online

Authors: Bob Drury,Tom Clavin

DECEMBER 2, 1950

6

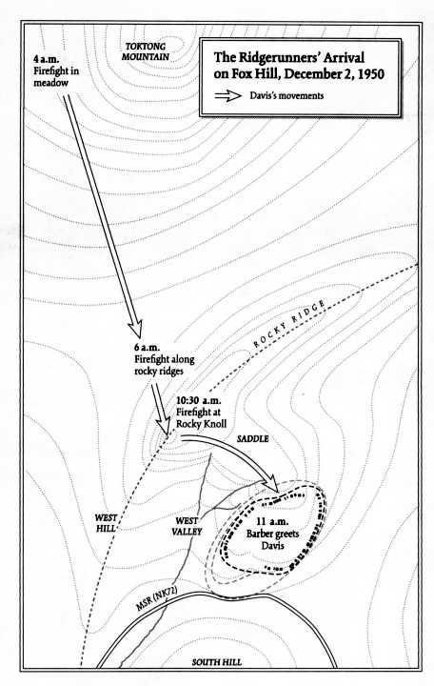

By 3 a.m., following another small gunfight, Lieutenant Colonel Ray Davis's Ridgerunners had been slogging overland for more than six hours, and had gone without sleep for nearly thirty. They were cold, hungry, and spent-nearly oblivious of the sporadic sniping from the surrounding peaks. How Company, the rear guard, had been given the responsibility of carrying the wounded from the meadow engagement, and its men had reached the limits of their endurance. They lagged several hundred yards behind the main force.

Davis called a halt. He established a temporary perimeter, to allow How to catch up. Every fourth man was instructed to stand alert while the rest crawled into mummy bags-which, by Davis's order, were to remain unzipped. The men could rest but not sleep. The NCOs and fire team leaders circulated among the Marines who were lying down, urging them to stay awake. To Lieutenant Joe Owen, the men curled up in the snow looked like Eskimo sled dogs. Fourteen hundred yards to the southeast, less than a mile over the final rocky ridge, rose Fox Hill.

No sooner had the men of Baker, Able, and Charlie dropped where they had stopped than How radioed Davis for help. Its own rear guard had collided in the dark with two companies of Chinese, and it was taking heavy casualties. Davis sent two platoons-one each from Baker and Charlie-to bail out How, but by the time they arrived How's commanding officer had maneuvered his few men to the high ground above the interlopers and scattered them.

The Marines of Baker and Charlie escorted How back to the makeshift bivouac. Lieutenant Chew-Een Lee circled the encampment, yelling toward the hills in pidgin Chinese, urging all enemy combatants to surrender.

About an hour before daybreak Davis was patrolling the perimeter when he noticed a young Marine kneeling on an elevated knoll, silhouetted against the skyline. Jesus Christ. "Hey, Marine," he hollered. "Get down. Don't you ..."

A sniper's bullet dented Davis's helmet, knocking him flat on his back into the snow. Corpsmen rushed over. He waved them off and summoned his platoon leaders. It was time to implement the plan of attack they had discussed earlier, in the mountain meadow.

As a gray dawn arrived Lieutenant Kurcaba led what was left of Baker Company, a few more than one hundred Marines, up the back slope of the rocky ridge of Toktong-san. Davis had ordered him to make contact with Fox Company on the other side. On their approach Kurcaba's men ran into the remnants of the same Chinese battalions that had pinned Fox down for five days, and the resistance was heavy. Chew-Een Lee-an inviting target in his bright marker panels-took another bullet, again in his wounded right arm, this time closer to the shoulder. Joe Owen rushed to his side and emptied two clips from his own MI. Lee, on his knees, began screaming in Chinese. So many enemy riflemen jumped from their hiding places to get a better bead on Lee that Owen guessed he was taunting them. Some even charged toward Lee. As fast as they came, the rest of Baker Company took them out; still, they kept coming.

When Baker faltered, Davis led Able and Charlie into the breach. The battalion commander felt as if he were running in slow motion. Cold and exhaustion had taken a worse toll than the sniper's slug. As the firefight grew more intense, his brain started to form orders that he simply could not get out of his mouth. In the middle of a sentence he would lose his train of thought. He hollered to his lieutenants, asking if the commands he was issuing made any sense. They were not sure, either, but they continued to fight.

Now-as Kurcaba had predicted to Owen-their Marine training seemed to kick in. Simply out of habit, the men in the four rifle companies did indeed put one foot in front of the other, and gradually they cleared a path up to the rocky ridge.

At 7 a.m., while the fight on Toktong-san raged about him, Davis's radio operator shouted to his battalion commander, "Sir, I've got Fox on the radio'."

A pallid sun had just risen over the southeast corner of Fox Hill when John Bledsoe woke up. His hole mate Phil Bavaro was pounding his fists on Bledsoe's back and shoulders. Bledsoe was blanketed in six inches of fresh snow. Bavaro was too spent to show anger. He calmly informed Bledsoe that after his feet had gone totally numb he had decided to let his friend sleep through the night. He had taken the entire twelve-hour watch. But Bavaro was already hatching schemes to make Bledsoe pay back the favor.

Bledsoe was dumbfounded. How do you thank a man for such an act? His guilt increased as he watched Bavaro rip off his shoepacs and wool shoe pads. Bavaro's sweaty wool socks had frozen to his feet. He gingerly removed them and shook out the ice crystals. Candle-white splotches of frostbitten flesh ran from his toes to his ankles. He stuffed his shoe pads and socks under his armpits, and jammed his bare feet into his sleeping bag. He remembered the goddamn Reds who had stolen his pack with his spare socks from the hut on the first night. Even when he was wrapped in the mummy bag, his feet began to feel as if they had been thrust into a campfire. He inspected them again. Now they were blue and beginning to swell. He knew enough about frostbite-trench foot some Marines mistakenly called it, dredging up institutional memories of the flooded, muddy trench warfare of World War I-to realize that as long as his feet were in pain he still had a chance, that the tissue was not yet completely dead.

He cursed softly as he put his feet into his damp socks, shoe pads, and shoepacs. Even to stand up now was torture, but Bavaro had heard that spare socks might have been dropped by one of the cargo planes. Steeling himself, he began the long limp up the hill toward the aid station.

Before reaching the med tents he came upon the stack of American corpses. He saw a pair of dry shoepacs sticking out from beneath a poncho. He banished the thought of taking them-it was too morbid, too disrespectful. At the aid station a corpsman told him that the airdropped socks were only for the wounded, and at any rate they had all been distributed. Bavaro, slump-shouldered and miserable, trudged back down the hill.

Down near the spring the bazooka man Harry Burke crouched low, but there was no sniping from the woods near the South Hill this morning. He filled his canteen and edged over to the back of the large hut. He found the young Chinese soldier he had seen the day before, still leaning against the shack. The boy was frozen to death. A cursory check of the body revealed no new gunshot wounds.

At 8 a.m., Captain Barber, having spoken to Lieutenant Colonel Davis and anticipating the arrival of the relief column, continued to oversee the general cleanup in preparation for the evacuation of the hill. At one point, however, he took a moment to stand by himself and gaze over the slopes, which were clean with new-fallen snow. His company had climbed this hunk of granite with 246 Marines and Navy corpsmen. Slightly more than eighty "effectives" remained, most of them wounded and frostbitten. Only one of his officers, Lieutenant Dunne of the First Platoon, remained unscathed.

Barber thought of an old saying that applied to his outfit: uncommon valor had become a common virtue. For a moment, both pride and sadness overwhelmed him. He took a final look at the hill and got to work.

He ordered empty C-ration tins, excrement, and sundry trash buried and all surplus equipment belonging to the wounded stacked near the med tents. A detail was formed to lug captured gear to the level terrain just off the road near the huts. There it would be set afire. Another squad was directed to be ready to strike the med tents and warming stoves on his signal. Finally, eight Marines were sent to move the stack of American corpses farther down the hill so that these could be more easily loaded onto the trucks that would arrive with Litzenberg's main column. This was a job no one wanted.

Barber also asked Sergeant Audas to take a squad to the hilltop for one final enemy body count. Audas returned with his best estimate: more than one thousand Chinese bodies lay on the ground from the saddle to the eastern crest and down the east slope. This number did not include the dead of the nearly four Chinese companies across the MSR and farther on toward the South Hill. How many of the enemy had been killed during the recon patrol's firelight at the rocky knoll, or by the machine gunners on the rocky ridge? How many more had been retrieved by their comrades, particularly during the confusion of the first night's battle, and lay in caves or shallow graves on the West Hill or the higher ridges of Toktongsan? Neither Barber nor Audas could hazard a guess.

What was certain was that Barber's company, outnumbered by at least ten to one, not only had survived five days and nights of frozen firefights but had dispatched more than three-quarters of the enemy it had faced.

The noisy bustle around the aid station woke Warren McClure at 9:10 a.m. He stumbled out of the med tent and into one of the last flurries of what had been a heavy snowstorm. Someone had just started a fire, and McClure poured himself a cup of coffee and scrounged another can of peaches. He went back in and again shared the fruit with the paralyzed Marine.

Then he made another effort to retrieve his kit from the west slope. He had made it halfway across the hill, about fifty yards, when he realized that although he might indeed reach his old hole, he would never get back. He returned to the aid station and again plopped down next to Amos Fixico. Cigarette smoke curled around the bloody bandage encasing Fixico's head. But his buddy, as well as all the other Marines basking in the morning sunlight, seemed in high spirits. They knew by now that relief was just over the rocky ridge.

McClure caught his breath and returned to the med tent. He found a rag to wipe the brow of the paralyzed Marine and fell asleep again.

At 10 a.m., Lieutenant Colonel Davis again made radio contact with Captain Barber. His column, Davis said, had fought its way nearly to the crest of the far side of the rocky ridge. He wanted to come in. The two officers spoke in a vague, unofficial code, but Barber recognized the unspoken message: Hold your fire!

Barber warned Davis about the Chinese still holed up in the caves and crevasses around the rocky knoll and-somewhat mischievously -volunteered to send a patrol out to escort the Ridgerunners across the saddle. Davis was not even sure if he would find any Marines of Fox Company able to walk, much less fight, when he reached Fox Hill. And here was their commander offering to take Davis's men in hand. Davis recognized the gentle barb as a Marine officer's dark humor leavened by esprit de corps-and respectfully declined the offer. He did, however, say that he carried no radios with a frequency to call in air support. He asked if Fox Company might contact the Corsairs to soften up the route. Barber said yes and warned Davis to get his point platoon back off the ridgeline and to keep the men's heads down.

The squad of Corsairs appeared at 10:20 a.m. Once again they did their best to incinerate the rocky knoll and the rocky ridge. As they flew off, Barber ordered all of Fox Company's 81-mm mortar units to begin a second barrage against the same positions. Then, as a feint, he sent a squad across the saddle as a patrol to harass any surviving Chinese troops.

At 10:30 a.m., Walt Klein shook the snow from his helmet and inched out of his hole on the eastern crest of Fox Hill. He spotted the hazy outlines of several dozen men etched against the skyline, marching down the rocky ridge about four hundred yards north of the rocky knoll. He hollered for the platoon sergeant, Audas.

"Chinamen walking that skyline."

Audas lifted his binoculars. "Those are Marines," he said.

Klein, Audas, and Frank Valtierra leaped from their holes and waved their arms over their head.

"Now, ain't that the greatest sight you ever saw," Klein said.

The climb down the ridge was slow going, and Lieutenant Kurcaba's point company took forty minutes to pick their way to the rocky knoll, where they dropped out of sight behind the huge outcropping. The Marines of Fox Company heard gunfire, and suddenly scores of Chinese soldiers streamed from behind the big rock mound and down into the western valley. They made for the ravine and the woods skirting the West Hill. Some Fox Marines took potshots at the fleeing figures, but most were more interested in seeing who would emerge from behind the big rock.

At 11:25 a.m., the bedraggled Baker Company of the First Battalion, Seventh Marines, climbed down from the rocky knoll and began crossing the saddle. Sergeant Audas led a detail out to guide them through the trip wires attached to flares and hand grenades.

When Kurcaba and his exhausted men reached the crest of Fox Hill, their first request was for food. Guffaws exploded across the hilltop. Finally, a couple of boxes of C-rations were produced and handed out to the new arrivals. The Marines of Baker Company wolfed down the frozen chow without bothering to heat it.

Lieutenant Joe Owen dropped to his knees. His mind could not immediately comprehend the scene on the saddle. Hundreds, maybe thousands, of Chinese corpses littered the approach to Fox Hill. Many of the bodies seemed to be merely asleep, half buried under what looked like drifting white wool blankets. There was a straight line of snow-filled craters, hollowed out by Richard Kline's 81-mm mortars, along the land bridge, looking like stones just below the surface of a stream.