The Last Supper (6 page)

Authors: Rachel Cusk

We board the train and pass along the Serchio valley, among gentle green perspectives of hills and distant mountains, past melancholy Barga, swaying serenely over grassy plains and stopping sometimes at deserted stations that seem to stand in the middle of nowhere. There are weeds flowering on their platforms, and clumps of grass between the rails, and after a while we slowly pull away again. I feel that something new is disclosing itself, something to do with time. We are free: no one is expecting us. We look out of the windows. We listen to the tranquil hum of the engine. We watch the valley in the mild morning light.

*

Lucca stands in an unbroken circle of gigantic walls. They are forty or fifty feet high, dark, and so thick that over time they have become a land formation, a strange circular isthmus with lawns and trees and paths on the top. They were built in the sixteenth century to keep out the Tuscans, those gentle Chianti-quaffing folk, and now, in their retirement, with their neat paths and barbered lawns, they provide tourists with a circular bicycle ride and a view of the plains and mountains from their colossal shoulders. Outside them the city has spread its clutter, its traffic and car parks and residential suburbs, its strings of shops: within, in the old town, an atmosphere of unusual refinement prevails. Every infelicitous speck of modernity has been sieved out. When those walls were built, it was in ignorance

of what they would be called on over time to repel: Tuscans or car parks, it’s all the same to them. Of course, these beautiful islands of the past in their turbid oceans of modernity are to be found all over Europe, in England too. At the heart of every hideous human settlement we find an image of our predeceased ancestor, aestheticism. It is our lot to defend that image, lifeless as it may seem. But the forbidding walls of Lucca do a more thorough job of it than most.

The bicycle is the accepted means of transportation here: the motionless air rings with their shrilling bells. Resolute bluestockings fly by with a warning

glissando

; professorial men in tweed jackets glide past, erect, with a

ping!

Groups of students and tourists pass along the old paved streets in weaving flocks, their many bells trilling and squawking as they go. For a while we walk, but we are birds without wings. We return to the city gates, where earlier we passed numerous bicycle shops without realising their significance. There we are given bicycles at a daily rate, in descending sizes like the furniture of the bear family that so preoccupied Goldilocks, whose tastes and proportions ruled their little owner to the degree that she could feel no sympathy with the world. I have never cared for the

moral of that story, nor for Goldilocks either: but the bears in their shameless conservatism I like least of all. I do not want to be Mrs Bear, with her middle-sized possessions, her brown motherliness, her sturdy bear’s body that contrasts so with the blonde whimsicality of her intruder. I do not want to be the Bear family, pedalling sedately on their bicycles of descending sizes.

But it is too late: up we go, up to the ramparts, where a breeze rustles the great skirts of the trees and the laid-out paths and lawns, so strangely elevated, recede down their long, curving perspectives. It is four kilometres all the way round: on one side there is the plain with its dove-grey light, its pale geometry of roads and buildings and here and there the classical forms of Lucchese villas, sunk in their soft beds of trees; on the other there is the slowly revolving ancient town. We see its bell towers and palaces, its piazzas and churches, the Guinigi Tower with its mysterious forested top, all seeming to turn like a jewelled mechanical city pirouetting on a music box. We go faster and faster, flying along the gravel paths, whirling through colonnades of trees, but the strange feeling persists that we aren’t moving at all; that the city is rotating while we are standing still.

In the afternoon we wander the paved streets: we visit the Piazza dell’Anfiteatro, which stands on the site of a Roman amphitheatre and retains its cruel elliptical shape. It has vaulted sides with low archways that faintly suggest the introduction of victims, though there are cafes there now and souvenir shops. The children buy a souvenir each, a little china bell and a ceramic bowl with

Lucca

written on them. There are people here, people in the churches and the cafes, up the towers and on the streets. They seem perfectly satisfied with all this magnificence: they seem content. They look at the Roman remains and the Palazzo Pretorio. They lunch in the Piazza Napoleone, named after Napoleon’s sister Elisa, who once governed the principality of Lucca. What is it to them, I wonder, this place whose layers reach down so

strangely, so intricately into time like a crevasse into the frozen mystery of a glacier? What, in a personal sense, does it signify? They come to marvel at the sublimity and passion that human beings once were capable of: I wonder why its monuments fail to shake them out of their composure. Do they not want to be passionate themselves, and sublime? Why do they care so much for it, with their video cameras and guidebooks and long lenses, with their money belts and sensible shoes, when it cares so little for them?

In the Piazza San Martino is the

duomo

. Its tiered tower is slightly askew and its front with its three colonnaded layers has an ornamental severity, like the lace on an old lady’s mantilla. It seems a little reproachful, in its grey and delicate austerity. The bluestockings whirr by, ringing their bells. There is a sculpture above the porch, of a man with a cloak and a sword on horseback. Another man stands beside him: the cloaked rider is turned towards him, though not to smite him down. It is his own cloak his sword is directed at, for he is St Martin, who was asked for alms on a cold day by a wayside beggar and unexpectedly responded by sawing his garment into two. The beggar was presumably pleased: half a cloak, I suppose, is better than no cloak at all. The night after this event, St Martin is said to have seen a vision of Jesus in a dream, wearing the half he gave away. I am surprised by this: visions of Jesus rarely advocate the morality of fifty per cent. Inside the

duomo

we see the sculpture of St Martin again. The one outside is a copy: the original has been brought in, to protect it from the weather. It is more affecting, this ancient, eroded image, for its symbolism has become the unique form of its vulnerability. The rain and the wind have rubbed away at St Martin: he may as well not have kept his fifty per cent after all. He shields but he is unshielded, and were it not for the different kindness of our curatorial age he would be whittled down to a peg of stone.

Nearby there is a painting by Tintoretto of the Last Supper. It is small, or perhaps it is merely crowded, for it contains many figures. Generally Tintoretto’s human beings are large things: life is all, or seems to be. And indeed the figure of Jesus at the far end of the table is the painting’s furthest and smallest point, as though to express the remoteness of the conceptual, of self-sacrifice, in a busy room where a woman reclines breastfeeding her baby in the foreground and men are leaning across the table to talk, eager living men with brown skin and muscular arms, talking and gesticulating around a table laden with food and wine. The two men at the nearest end of the table are distinctively dressed: one wears a purple tailored coat, and the other has the sleeves of his shirt rolled up to the biceps. They are talking together: they possess a great reality, the reality of the living moment, of the chunks of bread and the half-drunk glasses of wine, of the plates and crumpled tablecloth and the woman who watches their conversation instead of the baby at her breast.

Tintoretto (1518–1594):

Last Supper, c

.1592. Lucca, Cathedral. © 1990. Photo Scala, Florence

I look at this painting for a long time. I try to understand it. I try to understand the difference between the people close to Jesus at the far end of the table and the people down at this end, close to us. The closer they are to us, the less attention they pay him. Yet it is more beautiful down here; it is richer and more alive. At the other end, Jesus bends to put bread in the bearded mouth of Peter and Peter ardently clasps his hands. That, too, is a moment of life in this painted scene. I don’t doubt that Tintoretto believed it himself. But the reality of the man in the purple coat, whose hand rests on a fallen keg of wine, is too powerful. Perception is stronger than belief, at least for an artist, who sees such grandeur in ordinary things. In this it is the artist who is God. And it is a strange kind of proof we seek from him, we who are so troubled by our own mortality, who know we will all eat a last supper of our own. We want the measure of the grandeur taken. We want to know that life was indeed what it seemed to be.

On the train home we find our guidebook in a bag, and discover that we have seen virtually nothing of the glories of Lucca, neither the National Museum nor the Villa Guinigi, neither the Filippino Lippi altarpieces nor the della Quercia

engravings. The children sit in a corner, studying their souvenirs. Later we will learn to fillet an Italian city of its artworks with the ruthless efficiency of an English aristocrat de-boning a Dover sole. We do not yet know the hunger that will take us in its grip. But for now we are perfectly satisfied; like all the other tourists who daily circumnavigate Lucca’s terrifying walls, we are quite content. In a few days we are going south, to the house that will be our home until the summer comes. I wonder what awaits us there. I wish I knew better, how to tell the difference between the good and the bad, the truth and the imitation. I wish I could learn how to read the structure of life as weathermen read the structure of clouds, where the future must be written, if only you knew what to look for.

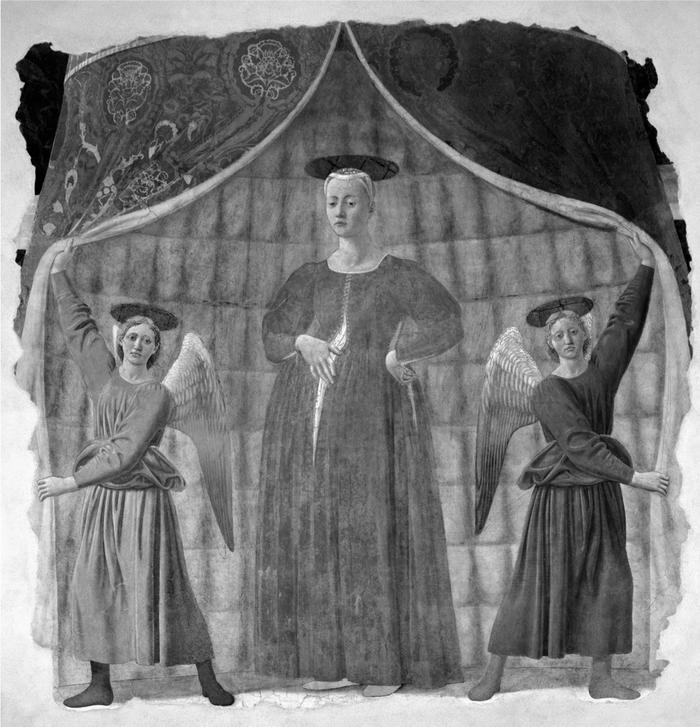

The Pregnant Madonna lives in the village, beside the main road. They keep her in the old schoolhouse. It is a small, plain, white cement building, distinct from the precarious earth-coloured terraces that form silent, dark, delicate chasms around the narrow village streets, winding uphill to their own exiguous and mysterious summit. The village suffered an earthquake in 1917, in which the original school building was destroyed. We meet an elderly lady who tells us how on that day her throat was sore and her mother let her stay at home. More than half of her classmates were killed by the building’s collapse. These days the school is situated in a modern complex elsewhere and the small, vaguely funereal, white cement building that extemporised between tragedy and renewal houses the Madonna.

On that side of the village the road, leading nowhere in particular, is quiet. Once or twice a day an air-conditioned coach appears at the narrow intersection like a vast, snub-nosed whale, venting great sighs from its hydraulic brakes, and clumsily manoeuvres itself into place outside the old school. From its side tourists are disgorged, people from Germany and Holland, people from Japan, come to unearth the Madonna from her obscurity here by the side of the road. The rest of the time the building stands brilliant white and silent in the sunshine while the curator sits on the front steps, reading the

Corriere della Sera

and smoking Marlboro Lights. He is a man with business interests, and has dogs that are reputed to be the most voracious truffle-hunters in the region.

Often a woman is sitting on the steps in his place, keying messages on her mobile phone or talking over the little gardens to the lady who runs the cafe a few doors up. There are quite a few women prepared to keep an eye on the Madonna for the truffle-hunter. I often pass the old school and see one or another of them, half-bored, half-dreaming, suspended somehow in her posture there on the steps, and they seem to me to have a certain kinship with the Madonna herself, with her weary pregnant slouch and her ambivalent mouth. Not so long ago the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York offered three million euros for her, and the Italian government paid the ransom. At five o’clock the truffle-hunter or one of his molls locks the little wrought-iron gate at the bottom of the steps and knocks off for the day, pocketing the key and wandering away down the quiet road that is half-shadow, half-light.

We are staying not far away, in a house up a steep dirt track on top of the facing hill, with a kilometre or so of intricate Italian fields in between and a soft green valley on the other side. This house is to be

casa nostra

for the next two months. We arranged it all in England, not knowing what we would find. I saw photographs of it, as I saw photographs of many other houses, photographs that filled me with strange feelings of voyeurism: pictures of rooms with enormous three-piece suites, of knick-knacks and blackened fireplaces, of strangers’ beds and kitchens and bathrooms, all suffused with an atmosphere of sadness, of impermanence, as though the people who lived there had been lost or gone astray. By contrast, the photographs of our house were so subtle as to reveal virtually nothing about it at all. They were studies of light and shade and perspective, abstract and beautiful. If only in matters of taste, I felt sure that the person who had taken them could be relied on.

The house is near Arezzo, on the eastern edge of Tuscany, where a road continues east through a gorge whose steep wooded sides plunge down on either side from far overhead.

The road winds on and on through this green chasm-like wilderness. When it comes out, it is on to the flattest of plains. It is this proximity of extremes that tends to give the Italian landscape its atmosphere of miniaturism. It is like travelling through the plaster contour maps that hung on the wall of our geography room at school and that always seemed so enchanting, with their cosy little woods, their baby hills and streams, their gnomish dwellings and small, scaleable mountains. In the distance a village stands as though on an island, its shining roofs and tower crowning a mound of hill that rises alone out of the flat terrain. Beyond it are purple hills of an unearthly

appearance, dream-like and remote, as unreachable as the distances of a painting. The large soft sky rolls with cloud: the light falls in columns on the flat fields. The road goes up through the village with its deep, narrow streets and out the other side. Now it runs among hills, orderly and wave-like and neatly cultivated, with stone houses and ancient castellated towers in the folds.

There is something almost comical about them: they are so childlike and undulating and miniature, so picturesque and unreal. There is a sign by the roadside that reads

Umbria

, but our house is not in Umbria. The road goes there, meanders away and disappears into its green wooded hills. At the same place there is another sign, small and hand-painted, that points right. It reads

Fontemaggio

. A dirt track threads its way across the fields and up a hill, at the top of which stands a house. In the late afternoon the light suddenly ebbs away from the wave-like hills. I was to notice this often, how night fell in the valley, not through the arrival of darkness but through the departure of light. The darkness has no substance: it is merely an absence, a suspension. At this time of day the house makes a black shape on its lonely hilltop. Its silhouette is imposing, and far from friendly. We look at it from down below: we seem, all of a sudden, so far from home, so self-willed and rootless. And yet it is this feeling that is the decisive stroke in the process of our liberation. Looking at those dark, distant windows our bonds are cut, our anchors weighed. We turn the car off the road and creep slowly into the quiet of the lightless fields.

*

There is a bang at the door. It is a man. He is wearing an anorak with a hood, for it is raining, though so softly that it is more like mist. His name is Jim: he introduces himself, with handshakes all round, and distributes his card. I look at it. It says

Enjoy a drink! Jim Balercino, Scottish Taxi Service

. For a moment I misunderstand it, for it seems to suggest that it is Jim who will be offering drinks to his passengers, and that that is what a Scottish taxi service is. In fact I am a little disconcerted

generally by his arrival, with his broad Dundee accent and his anorak. It gives substance to my fear that this landscape is inhabited entirely by foreigners, all tussling over their threadbare scrap of Italian culture. I have found one or two paperbacks in the sitting room, with titles like

Extra Virgin

and

Tuscany for Beginners

(‘Love and War in a Hot Climate!’), which I feel certain our gracious owner must have allowed to remain there either ironically or by mistake.

But Jim has not come to tout for business. He has come to make sure that we are all right. The telephone number on his card is for our own personal use, should we find that we are not all right. He lives just over there, on the opposite hill, where this morning, looking out of our window, we saw what the darkness had hidden from us the night before: a great castle, with a village at its feet. That is the village where Jim lives. It stands on its hill and we stand on ours, and the valley floor lies in between, a distance of perhaps five hundred metres as the crow flies, though Jim, of course, lives in Umbria and we do not. He has lived here for fourteen years. This does interest me, if only in the context of

Italian in Three Months

. I wonder how well he speaks it: I imagine his Dundee accent sitting on his tongue, as stubborn as a stain. I am enthralled by the prospect of his fluency, for fluent he must be, after all this time. But Jim claims not to speak any Italian at all. He understands a bit, he says, but he can’t really speak it. He stands there in the hall, reiterating that we must ask him for whatever we need. He’s a sort of unofficial minder, he says, for the Brits that come to the area. He chucks the children under their chins. But he seems a little mystified by us nonetheless. No one has ever rented this house for such a long period, he says. Usually they just stay a week or two. Before he leaves, he tells us that on Sunday nights, at the bar in his village, there is some kind of festivity. He calls it ‘cha-cha’: I have no idea what it is, but I don’t doubt that it will be a breeding ground for Jim’s pet Brits. Mildly, he exhorts us to come. The kids’ll enjoy it too, he says, chucking them again. Sunday night is tomorrow. I am determined not to

go: I would rather spend a whole evening studying the agreement of the past participle with the direct object pronoun. I would rather spend the evening reading

Extra Virgin

.

The

Madonna del Parto

,

c.

1450–70 by Piero della Francesca

In the afternoon it rains harder. We can’t turn the heating on and the house is cold. A pall of wet grey mist hangs over the valley. The castle looks sombre and beautiful, in its shroud of mist and rain. After a while the rain stops and the others go out for a walk. I remain at home to investigate the

proprietario

’s library. There are a great many books about Renaissance art. I turn their pages; I glance at their Madonnas and Crucifixions, their Annunciations and Resurrections; I probe their texts a little and

turn again. I feel that I am standing on the edge of an ocean of knowledge. It is a beautiful ocean, and not uninviting, but all the same it requires my complete immersion in a new element. I don’t know how to start; I don’t know where to breach these waters. I pick up a little book about Piero della Francesca, for there is a print of one of his paintings hanging in a frame in the hall. Straight away I see names that are familiar to me, Arezzo and Sansepulcro, and even the name of our own village on its island in the plain. There is something called the Piero della Francesca Trail, and it appears to run right past our door. I imagine it as an actual path, zig-zagging its way across the fields. Piero was born five miles away, in Sansepulcro, in 1410. His mother was born in our village: that is why the

Madonna del

Parto

is here. There is a print of it in the book. I am startled by it: it is like no Madonna that I have seen before in my life. What a strange expression she wears; what an abstracted, ambivalent look. It is a look that has been known, not imagined. It is a look that I am surprised to see on a human face. Such things as it expresses were not, I thought, visible to the eye.

It is raining again. The water batters hard on the roof; I look out of the window and see it falling in swathes across the valley. I run outside with my arms full of coats and umbrellas, meaning to go and find the others, and discover them standing on the front porch. A car is disappearing down the drive: it is Jim’s taxi. He has just brought them home. They were walking up through the valley. They were in his village when it started to rain.

The children are beside themselves, wanting to tell the story. It seems they took shelter under a stone loggia at the front of a beautiful house in the village square. They are standing under this loggia when the front door opens and a lady invites them inside. She leads them through great marble-floored rooms into her kitchen, where a fire is lit and there are children sitting around a big table. They are invited to join them: their clothes are dried before the fire; they are given drinks, and things made out of chocolate, things so delicious that they are unable fully

to describe them to me. This lady, Paola, lives in Florence with her husband and children, but in the holidays they come here, to her childhood home. Outside, the rain has become a torrent. Paola wonders how her visitors are to return to Fontemaggio, and they mention that they met a taxi driver called Jim. Perhaps they could use her phone to call him. Paola laughs. There is no need to call: Jim lives here. He rents the top floor of the house, with its beautiful views of the hills towards Arezzo. They go up the stairs and there’s Jim, watching a tennis match on television. The children are amazed. Immediately he dons his anorak to take them home. He will accept no payment. They should see it as a favour.