The Latte Rebellion (20 page)

Read The Latte Rebellion Online

Authors: Sarah Jamila Stevenson

Tags: #young adult, #teen fiction, #fiction, #teen, #teenager, #multicultural, #diversity, #ethnic, #drama, #coming-of-age novel

Best of luck on your studies as you finish a stellar senior year!

“‘… Sincerely, Jerkface D. Buttmunch, Assistant Director of Admissions,’ ” I concluded miserably, throwing the letter down on Carey’s kitchen table and wiping my swollen eyes with an already-soggy paper napkin.

“Oh, Ash,” Carey said, shaking her head. “This isn’t necessarily a terrible thing. Where else did you say you got in? What about UCLA? That’s still an option, right? What about your backup schools?”

I paused and took a deep breath, trying to calm down enough to talk again.

“Carey,” I said in a hushed voice, “you can’t tell

anyone

, but I didn’t apply to UCLA. Or any backup schools. And I was wait-listed at Berkeley, too. I applied to a special public policy major in a really small program and they put me on a waiting list!”

“

What?

I can’t believe that,” Carey said. “You’re still ranked at least fifth in the class, even after last semester, because you’re taking all Honors and AP classes. And there’s the Key Club, and your Social Justice thing …”

“I haven’t gone to Students for Social Justice in ages,” I said. “Anyway, even if I had applied to UCLA, I still wouldn’t want to go. I wouldn’t want to leave Northern California.”

“Not since you met

Thaaad

.” She smiled, but I could tell it took effort.

“It’s not just that! I want to be able to see

you

, too. And Miranda. If she gets into that art school in San Francisco, then we could still hang out. Robbins was my last hope for that. I didn’t get into Stanford,” I croaked. “Harvard either.”

Carey was quiet for a minute, and tears started streaming down my face again. Finally, she said simply, “I’m sorry, Asha. I don’t know what to tell you. But you never know if a spot might open up later at Berkeley or Robbins. They’re both really impacted schools, you know that. Tons of people apply and not everyone can get in, even if they deserve to.” She put her hand on my arm.

“Yeah, whatever,” I said, a sob making me almost incoherent. “You’re right, and I’m stupid. And I probably wouldn’t have even gotten wait-listed if you hadn’t kept reminding me to study. Face it; I didn’t deserve to get in.”

You made your bed, now lie in it

, was what my dad would probably say if he knew.

“You know that’s not true,” she said, vehemently, but I couldn’t quite believe it.

The next day, Sunday, I woke up with my eyes crusty from crying myself to sleep, my throat raw and dry. I didn’t want to leave my room, but around ten I got up and took a long shower, letting the hot water scald my skin for as long as I could stand it. What was wrong with me? I’d spent most of my high school career as the perfect student, or nearly so. Carey and I had studied diligently; we’d gone to countless club meetings; and I’d even spent a few years with her on the soccer team. We’d done everything right.

Then somehow, things had gone wrong. And I was afraid the blame lay squarely with me. The Latte Rebellion had been my idea to start with. I convinced Carey that our plan was brilliant and foolproof. Then I’d gotten totally caught up in the hype, conveniently forgetting that we actually had high school to finish. Of course Carey hadn’t forgotten—she’d stayed on top of everything, including the senior class.

And here I was. I was left with two waiting list spots and no backup schools. And there was no way I could tell anyone, no way I would go crawling to my mom and dad on hands and knees to admit what had happened and ask for forgiveness. I couldn’t even explain this to Nani, because she didn’t know what a major mess I’d made of things.

I was screwed if I didn’t make it off one of the waiting lists. But I didn’t hold very high hopes of that. Who would actually turn down an admission offer from Robbins, so that a slot would open up for me?

I stepped onto the worn blue bath mat and dried myself off in the now extra-steamy bathroom, opening the window a crack. What a crappy year. I’d thought that senior year would be the apex of our high school careers, because we were on our way out of here. I’d assumed I would have my pick of the schools I applied to. I’d started thinking that Carey and I could go off to college together, and be roommates in a big, airy apartment in Berkeley, covered with indie band posters and hanging plants.

Wake up, Asha.

I’d probably never even get to move out. I started having horrible visions of living at home at the age of thirty, single and working in a gas station, my room adorned not with posters but with dashboard hula dancers and bobble-head wiener dogs from the gas station’s mini mart.

“What are you doing in there?” My mom knocked on the bathroom door, her voice muffled but unmistakably testy. “Hurry up.”

“I just got out of the shower,” I said, hoping I sounded suitably meek.

“I need to get in there so I can get ready for the teacher appreciation brunch.”

Great.

Everybody

was successful but me.

“I’m done,” I said, wrapping my towel around me, brushing past my exasperated mother, and stomping off to my room. I shut my bedroom door, not waiting for a reply. It felt like the world was against me and all I could do was keep sabotaging myself. No more. It was time to be proactive. I angrily yanked on a pair of argyle socks. If I couldn’t get into Robbins now, then I’d damn well go to junior college and transfer after a year. People did that all the time, right?

Maybe I’d ask Thad what he thought. I wouldn’t tell him about the whole parents-who-would-have-major-cow-upon-finding-rejection-letters thing. I’d just ask him what he thought about transferring to Robbins. Since he’d transferred to Berkeley, he’d be sure to have some suggestions.

I had about two months left in my senior year. That was plenty of time to rearrange my life. I’d managed to rearrange it for the Latte Rebellion; this couldn’t be that different.

I pulled on a pair of jeans and a random T-shirt and sat on the edge of my bed, phone in hand. But the minute Thad picked up, I was suddenly all freaked out again.

“So, how have you been?” I ventured, debating whether to tell him anything at all.

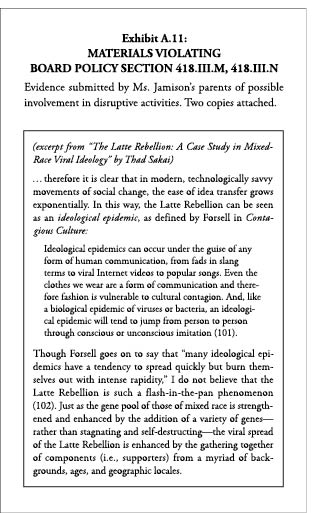

“Not bad,” he said. “I’m almost done with that paper for Dr. Malik’s class.” He hesitated. “Would you mind looking it over sometime before I turn it in? Since you … were a part of the Rebellion early on.”

“Um, okay.” I wasn’t sure what I could add that would be of any help. I wasn’t even sure I

could

add anything without incriminating myself.

“Thanks,” he said sincerely. “So, to what do I owe the pleasure of your phone call?”

“Do I need a reason?” I said, trying to sound coy rather than defensive.

“Nope,” he said, and I relaxed a little. But I knew I should get to the point and ask him about transferring from junior colleges. He knew about the process firsthand, and as an added bonus, there was zero chance he’d talk to my parents about it.

Come ON, Asha. Just do it.

As I opened my mouth, he said, “So how’s it going? Heard anything about where you might be going to college in the fall?”

Cripes, is he a mind reader?

“Uh … nothing worth sharing, really,” I said, a little morosely.

“Well, then tell me what isn’t worth sharing.”

I sighed. “I’ve been wait-listed at Berkeley and Robbins College. I don’t understand it,” I said, frustrated. “I’m ranked fifth in my class, I have extracurricular activities out the wazoo. My AP scores were good last year. What did I do wrong?”

“I’m sure you didn’t

do

anything wrong,” he said reassuringly. “Berkeley has to turn down tons of people; it’s just too crowded. There are so many reasons why a college might or might not admit someone. I read an article about it online back when I was applying to transfer—there’s this whole list of criteria you’d never even think about. “

“Like what?” I said, curious despite myself.

“Oh, jeez, like if you’re an athlete on a sports team they’re trying to develop, or if your parents donated money to the campus, they might flag your file. Or if you’re an underrepresented minority, like Native American.”

“Are you serious?” I said, incredulously. “That’s not fair. And who’s to say what an underrepresented minority is? I mean, on most of those applications I get to check

one box

and if I’m lucky it says ‘mixed ethnicity’ and if I’m unlucky it says ‘other.’ I shouldn’t have to play a guessing game just to fit into their system.” I was on a roll now. “I shouldn’t have to worry that I didn’t pick the right check box, and now they’ll reject me for being, say, too Asian, or not Asian enough. Or the wrong kind of Asian.”

Should I have joined the Asian American Club? Or even the Chicano Club? Neither of those had really seemed appropriate. I mean, Roger was in the former. As for the other … well, I was only a quarter Mexican. I just hadn’t felt like I belonged. Not anywhere. At the same time, I didn’t see why I

had

to belong to any particular group.

“Funny, I know just how you feel,” Thad said, irony in his voice. “The thing is, the system’s just not built to handle the increasing complexity of the racial landscape.”

“Racial

landscape

?”

“Sorry,” he said, sounding amused. “These are the amazing vocabulary words you learn in college, especially in Dr. Malik’s class.”

“Great,” I said. “You know, Carey

did

get into Berkeley. Obviously being at the very top of the class holds some weight.”

“It always does,” Thad said.

After a pause, I asked, “Do you think if I go to junior college for a year, I could try to re-apply and transfer to Robbins? Is it difficult?”

“Well, there are some hoops you have to jump through. But you got wait-listed, right? Have you thought about writing a letter of appeal?”

“What’s that?” I rolled over onto my back, the bedsprings creaking, and stared up at the Van Gogh sunflowers poster on my bedroom ceiling.

“If you didn’t get accepted, you can usually write a letter of appeal to the Admissions Office arguing your case and telling them why you should be admitted. And in a lot of cases, if you make a good enough appeal and your application was strong in the first place, they’ll let you in. I bet you could do it.”

“I’ll … have to think about it,” I said, reeling. I actually still had a chance. This was almost too much to take in.

“You should,” Thad said. “I’ll help you if you want. It’s only fair, if you’re willing to read my long-ass American Cultures paper.”

“Hey, you never said it was ‘long-ass’ before,” I accused him.

“If I had, would you have said no?” he asked innocently.

“Hmm.” I pretended to think about it.

“Aw, come on,” he said. “Is this the thanks I get for helping with your appeal?”

“Well, okay, I guess I owe you one.” I was glad he couldn’t see me blushing.

“Then it’s settled. I mean, your friend Carey wouldn’t be the only one who’d be happy if you moved to Berkeley.”

I blushed harder, warm all over, and grinned until my face hurt.