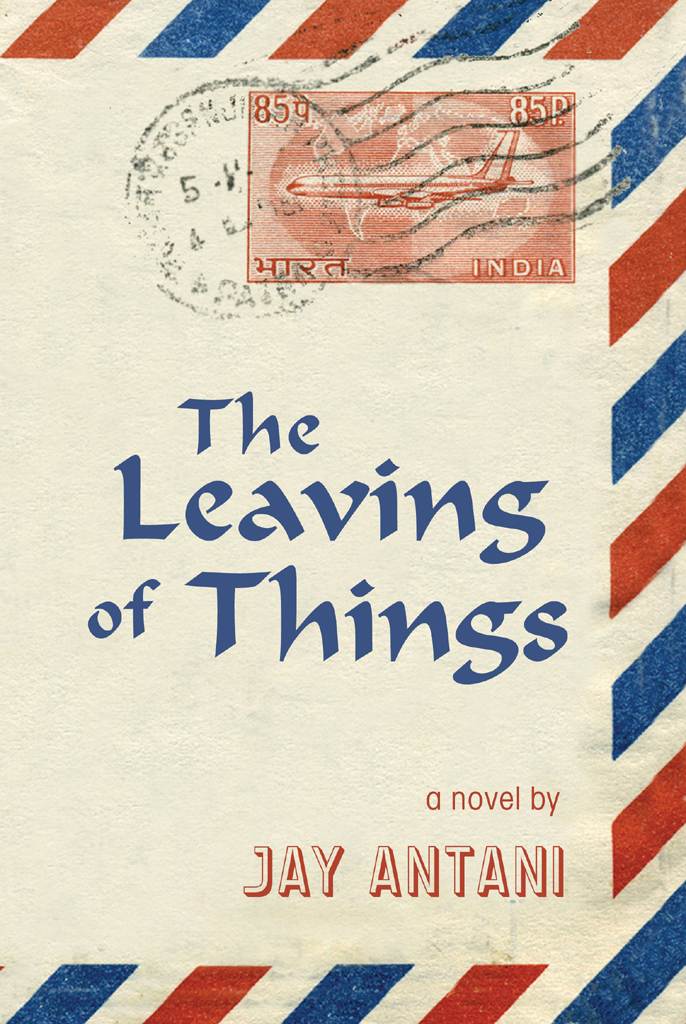

The Leaving of Things

Read The Leaving of Things Online

Authors: Jay Antani

The Leaving of Things

a novel by Jay Antani

Copyright © 2013 Bandwagon Press

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 0988419300

ISBN 13: 9780988419308

eBook ISBN: 978-0-9884193-1-5

Contents

1

June 19, 1988

I

ndia wasted no time with me. Monsoonal air acrid with soot and sweat and something else—a densely Indian spice—slammed into my head, my lungs, my senses as I approached the door. I fell in behind my parents, a crowd of exiting passengers, and I felt every bit the prisoner as we trudged from the plane into a tunnel of dirty white light.

I wanted so badly to turn around and fly back home to America—to tell my parents, “

Stop!

This is a

huge

mistake.” I didn’t want to be here—certainly didn’t want to

live

here—but life wasn’t about choices. It was a sentence handed down to you.

From the mouth of the tunnel, we spilled out into the arrivals hall of the Bombay airport. The place echoed eerily with jostling bodies and announcements from an ancient PA system. I stared at the mishmash of Hindi and English: “Customs,” “Immigration,” “Baggage.” But what the

Hindi really said to me was: “Kid, you’re not in Wisconsin anymore.”

In one hand, I clutched the hard plastic case containing my video camera—a high-school graduation present from my parents and my proudest possession. And in my backpack were a few prized

Rolling Stone

issues, my music tapes, and books (Bradbury, Tolkien, Vonnegut) I needed near me at all times.

Two children and a woman in a sari rushed past me, knocking my video camera case out of my hand. It clattered wildly on the floor. I half panicked, grabbed the case, and closed a tighter grip on it.

“Vikram, watch out,” my father reprimanded in Gujarati, a few steps ahead, “or you’ll lose or break that thing.”

The gall of that guy, I thought. Dragging us from our home to this, and all he could say was, “Watch out”? I stared at the back of his head. He was why we were here—because he’d taken a fancy job at some astrophysics institute in Ahmedabad, a city in Gujarat about an hour’s plane ride north of Bombay. He’d even given up his work visa—the one thing that kept us tethered to our lives in America—to make good on his scheme to move my mother, my younger brother Anand, and me back to what he called “the land of our roots.”

India may have been the land of

his

roots. But it was the land of

my

exile.

Elbows and suitcases nudged and jabbed at me as we made our way down a set of steps to the immigration hall. A child stepped on both my feet. A fat Sikh with an Air India shoulder bag pushed past me, bellowing instructions and waving wildly to someone in front of him.

I checked to see how Anand was holding up next to me. He looked half asleep. His face was drawn and his backpack slung low at his shoulder. He still wore his headphones. He’d kept them on most of the trip, while thumbing through his baseball magazine or one of his

Choose Your Own Adventure

paperbacks. I wondered if the headphones were his protection from all that was happening.

I glared at my father. He seemed so focused, so

delighted

to be back in India. You see, he had grown up in Ahmedabad. In fact, we had lived in Ahmedabad before we’d left for America eleven years ago. And it was there that my father expected my brother and me to settle right back in—Anand into the eighth grade and me into my first year of college.

And my mother, you ask? She’d worn her favorite

salwaar kameez

today—so

tickled

she must’ve been to be back here! She couldn’t care less about my brother and me, I’d bet. Clearly, that woman was in league with my father. I decided I wanted nothing more to do with them.

A frowning immigration officer stamped our passports. We collected our things—two large and two small suitcases—and went into the customs hall, about the size (and smell!) of my high-school gym and packed with worn-out travelers. Inspectors on the far side of the hall picked through passports, paperwork, everybody’s baggage like scavengers.

“Anand, what’re you doing?” my father asked sharply. My brother had unbuckled his suitcase and was rooting through it.

“Not now,

beta

,” my mother said.

But then, my brother found what he was looking for—his Brewers cap. He slid off his headphones and slipped it on.

“Why bother with that now?” my father shook his head, half amused, half irritated. He sized up the lines in the customs hall. “Forty-five minutes,” my father said.

“Forty-five?” my mother shot back. “This will take two hours minimum.”

My father turned to her and scoffed, “You’re sure of everything, aren’t you?”

Our connection to Ahmedabad left in three hours from the domestic terminal. I asked how far that was.

“Far,” my mother said.

My father pushed strands of thinning hair across his scalp and, with a long sigh, admitted, “Yes. It’s far.”

As long as we were waiting, I figured I’d better shoot some video. Since leaving Wisconsin (when was that—yesterday?), I’d been recording footage for a kind of video journal—my own firsthand reports on what it felt like to go from home-sweet-home America across Europe and on to the far Indian tropics. I planned on mailing the tapes to my best friends Nate and Karl and my girlfriend, Shannon, every month.

So I took the camera out of the case and panned across the hall, across the sea of faces, mostly brown faces, surrounding me: Some I recognized as tired fathers, much like my own father, in spectacles, short sleeves, and mustaches. I saw women who resembled my own mother, in their salwaar kameez, clutching purses, and duffel bags. They all stood silently or in tense conversation, tending to their luggage and their children.

They all looked so miserable, and here I was, no different from them.

I was one of them.

That got me dreading my fate even more, so I put the camera away and sat next to Anand on one of the suitcases, hoping for conversation.

His headphones pulled over his Brewers cap, Anand bobbed his head, drumming his fingers on the suitcase and humming to the tune that filled his head. “Who’re the Brewers playing this weekend?” I asked him as cheerfully as I could.

“St. Louis,” Anand said without even turning to me. “Last game of the series.” He resumed his humming, his drumming. I left him to it. But I couldn’t keep it bottled up like Anand; I needed to talk, to stay braced against the anxiety in my mind.

I glanced at my father again. There he stood, oblivious as ever to Anand and me, one hand at his hip and the other picking at his mustache, staring intently at the front of the line. No way was I ever talking to him again. I turned to my mother, who had propped herself atop a suitcase, tapping her chin.

“Are you happy?” I asked. “I mean, happy to be here?”

“Mm-hm,” she said, sort of, nodding absently.

I didn’t want to believe her.

These past few weeks, I had been building a wall between me and the tide of fear, depression, and panic I could now sense rising. I knew it was there, filling up my heart. Keep it together, Vikram. Don’t break.

So I thought of someone who calmed me—Shannon. Last I’d seen her was two nights ago. I thought of her hand reaching for mine across the table at Rocky’s Pizza on State Street after spending our final afternoon wandering the record and clothes shops.

“Couldn’t you stay?” were Shannon’s words while she pressed my hand. “I’m staying in the dorms on campus this year. You could stay at my parents’. Work this year, go to school next year.”

The thought of living in the basement at Shannon’s parents’ house made me laugh. There I’d be: the strange Indian kid, their daughter’s boyfriend, holed up in their basement. I told her I’d feel like some goddamn refugee.

“I couldn’t stay if I wanted to,” I said. “And I

do

want to.”

Even though I’d racked up straight A’s over the spring and raised my GPA more than half a grade point, the odds were still against me. I hadn’t bothered applying to a single school because my father had told me it was out of the question. He couldn’t afford to send me to an American college. “You’d be on your own,” he said and left it at that. So I tore up my college applications and shoved them into the wastebasket. It was upsetting as hell, but if India was inescapably my fate, I figured I’d better learn to live with it. Besides, there was still the matter of a student visa; I’d need one once my family left the country.

Shannon sighed. “A visa? But you’re American, why would you need—?”

I shook my head. “I’m not American. I was

never

American.”

This was difficult (and awkward) terrain, having to explain to your American girlfriend the finer points of your immigration status. Then, almost for my benefit, I added, “My dad couldn’t turn down the offer in India. It’s a big deal. Really exciting.”

I held her arm, stroking the freckles there with my thumb. She didn’t much like the freckles, but I loved them, loved how they burst into starry patterns below her eyes, her shoulders, and the spaces above her breasts. She cried then, across from me, quietly. I saw the tears running down her face before she wiped them away and, more than anything, felt flattered that anyone would cry over me, let alone this girl—this American girl. Sitting with her, touching her, I

felt like I had won her. And now, no sooner had she been won than I had to give her up.

God, I wished I could just snap my fingers, make the whole world stop so I could collect my breath and get my bearings. That’s when something did it: my parents’ and my brother’s silences, the acrid and smothering air, whatever it was, the anxiety broke and burst over the wall.

Shit.

I stood up from the suitcase, said I’d be right back, and set off looking for the bathroom. I needed a minute to myself, to hold off the panic. Steady, Vikram, but no, there it was—throbbing in my ears, thudding in my chest. I saw a sign for the men’s room and went in: a grimy cell with ancient sinks and urinals and closets hiding the toilets, everything reeking of mothballs. But I didn’t care. It was empty in here; there was privacy. I tried to quiet myself, hold the anxiety back. Then I heard someone walking into the room behind me, so I hurried into one of the closets and shut the door.

“Vikram?” It was my father. I didn’t say a word. I heard him humph and then the shuffling of his feet as he left, and he was gone.

Next thing I knew the wall simply crumbled away and the tears filled my eyes. I stood there over the pit toilet, my hands braced against the door of the stall, and kept my eyes shut. Don’t fight it, Vikram, no use now. So I let my feelings go. I saw the faces of all my friends, all the faces I might never see again. And I felt myself mourning—oh god, this was mourning! The feeling terrified me because mourning meant the end of something you loved. Was my soul acknowledging something I dared not admit to myself? I cried. It’s okay, Vikram. It’s no big deal. So you’re

mourning, it’s okay. Sooner or later, you knew it would come to this.

Let it go.

I waited for the choking and tears to subside and for my breathing to even out. I wiped at my face, breathing in the mothballed air. I stared down at the hole in the ground at a glint of water. I was breathing steady now. The storm had passed. I opened the stall door, took a few deep breaths, readying myself to face my parents and get on with whatever this would have to be.

2

T

hey took my video camera.

“How long are they going to hold onto it?” I managed to blurt out as we hurried through the terminal’s exit doors. My father grabbed two luggage carts from a train of them.

“Not long,” was all he would say.

The customs officer—a sweaty, jowly bastard—took the video camera and, with it, all that I’d recorded on the two videotapes I’d stored inside the case.

I recalled some commotion between my father and the officer about our not having a sales receipt for the camera, no proof of ownership. My father argued that the camera was our personal property, but the officer shook his head. “We detain item till you produce receipt,” he kept insisting. Finally, the officer grabbed the camera case and waved us on, saying we were holding up the line.