The Legend of Jesse Smoke (4 page)

Read The Legend of Jesse Smoke Online

Authors: Robert Bausch

When pro football got going, they pretty much adopted the college rules. By that time Warner had so popularized the forward pass, other teams, including Notre Dame, were also using it and the rules had changed to accommodate it. No more fifteen-yard penalty. An incomplete pass was just that. Nobody had to touch it and it didn’t go

over to the other team. Of course the rule book says all kinds of things about throwing the ball now, and hundreds of rules developed over almost a hundred years of playing. But for sure the first time anybody did it, there was nothing in the rules about it one way or the other.

There’s nothing to prevent a woman from playing in the NFL either, if you read the rules with the idea that all references to “man” or “men” are generic rather than specific. Like when somebody says, “The rights of man” or “All men are created equal,” they’re not talking about

just

men, right? I mean, that’s how they interpreted it in the beginning probably, way back there when the Frenchmen and Americans were writing all that stuff down. But nobody today would dare suggest that’s what it actually means. Similarly, in football the rules make all kinds of references to eleven men to a side, man-to-man, when a man does this or a man does that, and so on. But there is no rule, specifically, that says only men can play in these games and that no women are allowed. None. Go ahead, look it up.

You know, it’s funny now, but even way back then I was starting to believe in it. I’d remember what the ball looked like sailing off the tip of Jesse Smoke’s arm, and think,

Why the hell not?

A long time ago, quarterbacks called their own plays. They would take time as they played to set up certain strategies, or they’d go for it all right off the bat just to set the tone of a game. A lot of them practiced every day with the same receivers and learned speed, quickness, stopping ability, cuts at every angle, and just about anything else they could about a receiver’s movements. Most of the time they “looked” for a receiver running a planned route, and when they didn’t see him, they “looked” for another one running a different route. It was all done with sight; with what the quarterback could see. The great ones had terrific vision—from sideline to sideline. I’m talking about peripheral vision as well as twenty-twenty. They could pick a guy out when they weren’t actually looking his way, turn to him, and release the ball with a snap to get it to him. Since a receiver always knows where he is going and the quarterback has rehearsed the same play with him over and over in practice, it worked pretty well. Guys like Raymond Berry and Fred Biletnikoff who couldn’t outrun a tree

sloth but who had great hands and could cut (change direction) on a dime caught enough balls to get to the Hall of Fame. The quarterback knew how to find them and hit them as they moved.

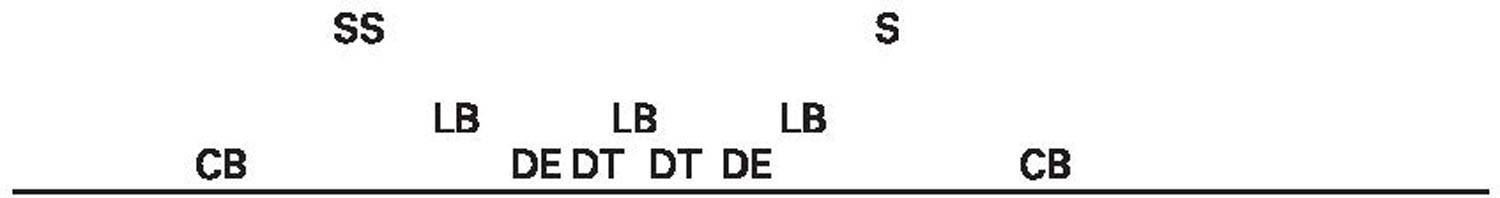

Over the years, a lot of that changed. But those changes were not brought about simply by altering the rules; strategy, how the men played the game—that changed as well. Even so, here, very basically, is how the defense on a team lined up on the field back then:

SS = strong safety, S = safety, LB = linebacker, CB = cornerback, DE = defensive end, DT = defensive tackle

The defense above is called a “four-three” because there are four linemen and only three linebackers. Lots of teams played this defense, including Engram’s Redskins.

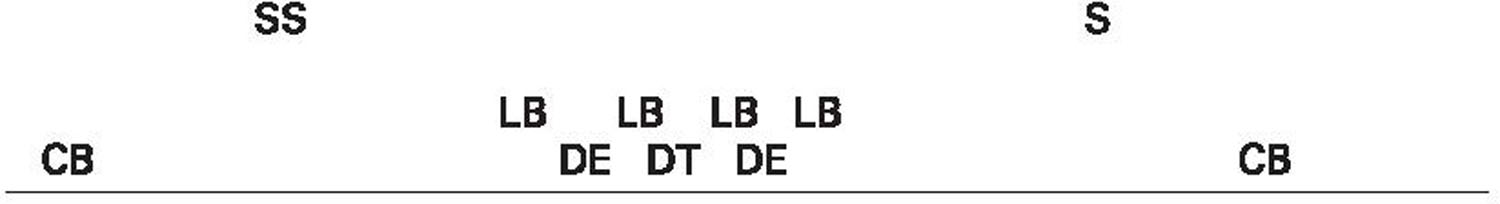

Some play what is called a “three-four.” They look the same except they’ve got only three linemen and four linebackers, like this:

The linemen and the linebackers concentrate mostly on stopping the run and getting to the quarterback before he can throw the ball. The cornerbacks and safeties are called “defensive backs,” and they try to “cover” the receivers to keep them from catching the ball. They either play “man-to-man,” which means they take on one of the receivers and go with him wherever he goes, or in what’s called a “zone” defense, in which they take an area of the field and cover that whenever anybody ventures into it. Sometimes if the offense is running plays with three, four, or even five receivers, defenses will take out

linebackers and replace them with extra defensive backs. One extra defensive back is called a “nickle” defense. Two, is called a “dime.” Four extra defensive backs is called a “quarter defense.” (I’ll explain the offense in a bit.) Sometimes a defense will play zone on one side of the field and man-to-man on the other. All of the possible combinations of those defenses come into play with the sole purpose of confusing a quarterback. Defenses always try to disguise what they are doing.

Over the years, combination zone defenses and man-to-man variations got pretty good at slowing down the receivers who could speed past a defensive back and break into the open, often by bumping the receiver and knocking him off his path while he passed through their zone.

Eventually defenses got so quick and so complex that the coaches themselves started calling the plays instead of the quarterback. This didn’t start until the early to mid-eighties or so, but it caught on and now we haven’t seen a quarterback who calls his own plays since Peyton Manning with Indianapolis and later the Broncos.

But that does not mean the quarterback doesn’t have real hard things to do. He’s got to be sure of himself without being cocky; he’s got to think fast and make decisions in a fraction of a second; he’s got to read what defensive players are up to—both recognizing alignments (how men are placed on the field, how they are moving when his own men move) and also characteristics of individual players he’s studied on film. (He might know something about a middle linebacker that the middle linebacker himself doesn’t know.) He has to know when a defensive player is feigning a blitz—that is, rushing the passer—and when he’s really coming.

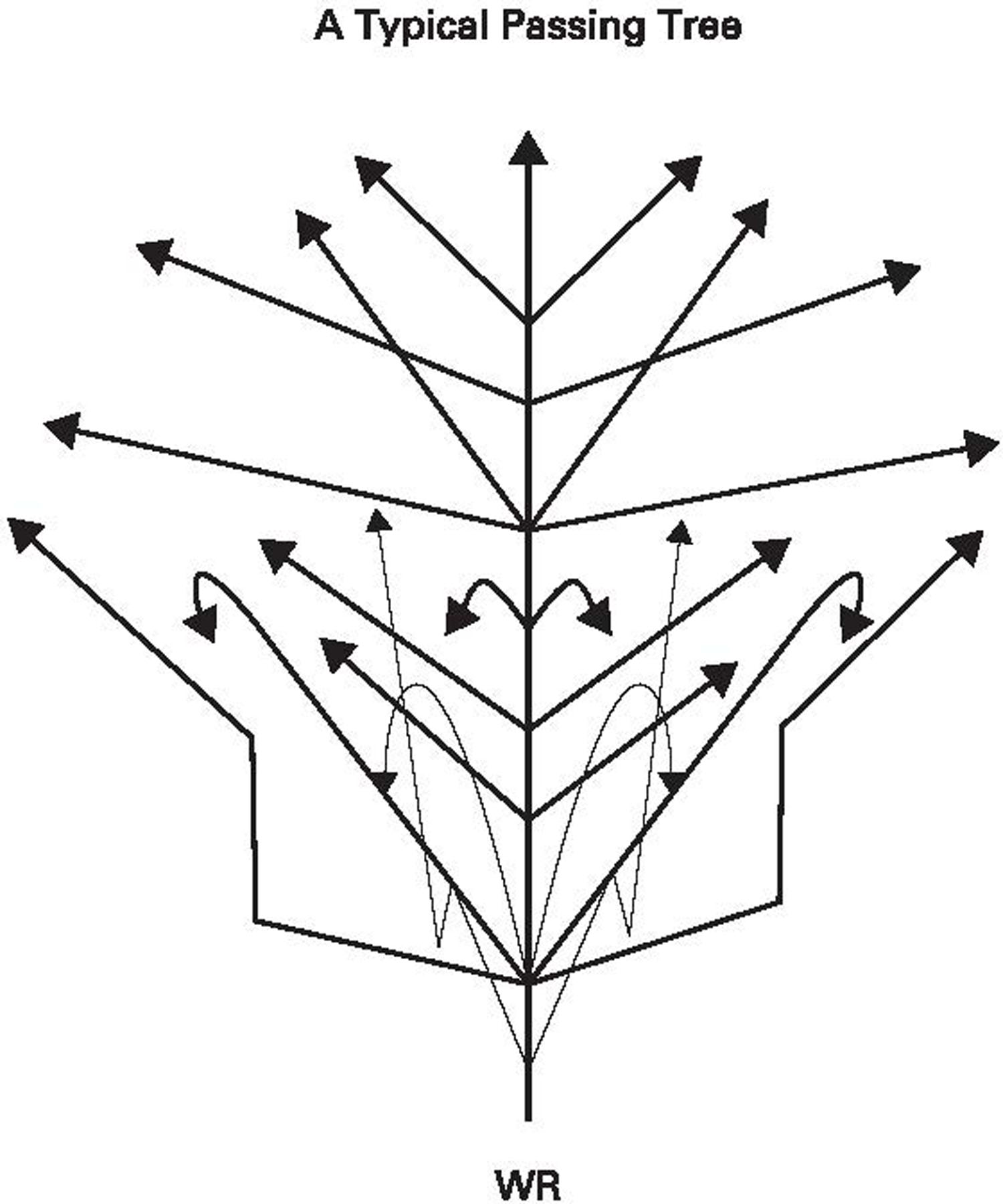

Now I don’t want to bore everybody with a lot of football terms or strategies. But this much is important to know if you’re going to appreciate what Jesse Smoke accomplished in her short career: A quarterback has got to see the whole field as if it was vertical in front of him instead of horizontal; as if he was looking down on it from above. Now, he’s got what’s called a “passing tree” for each receiver

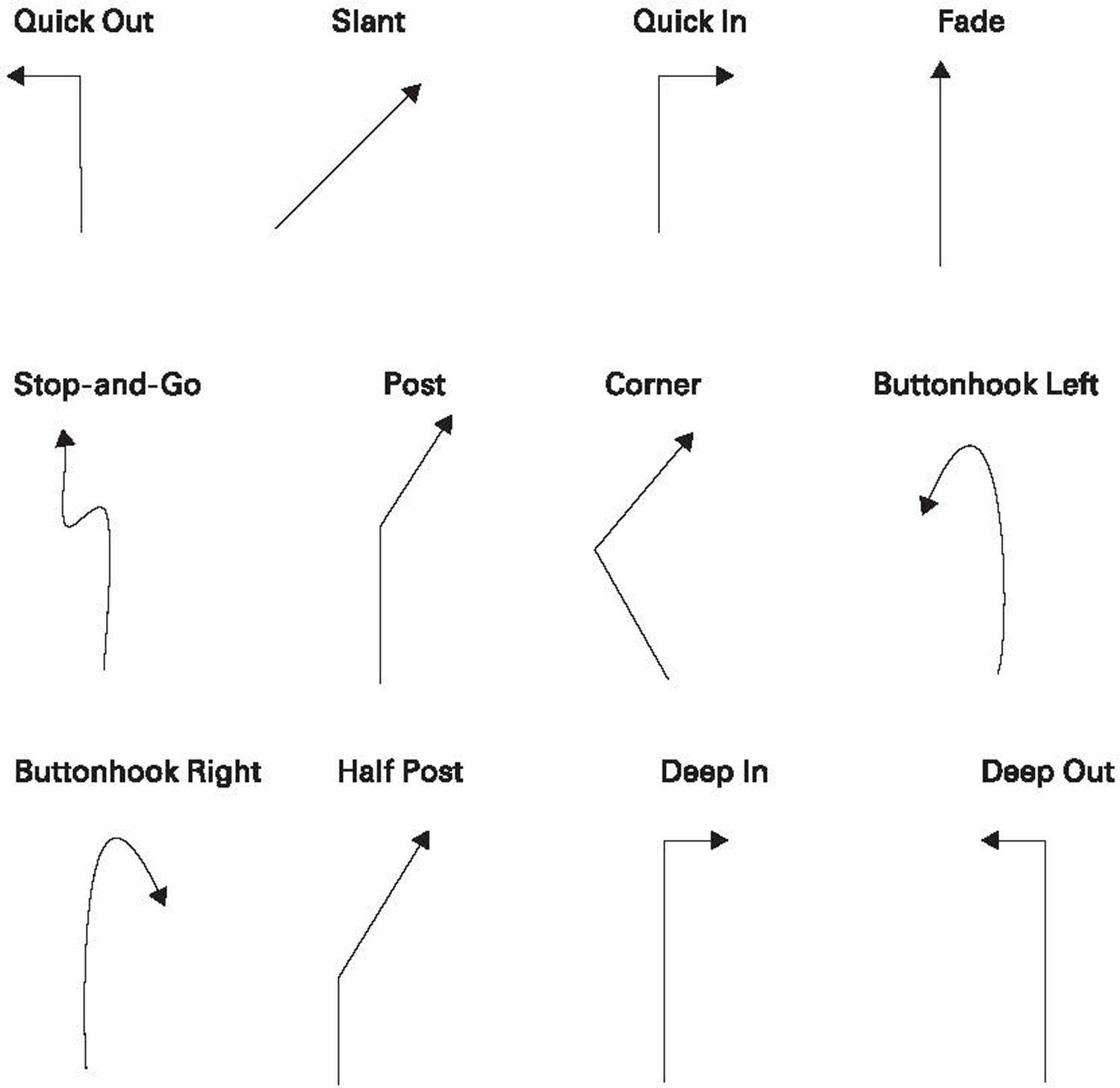

in his head and in front of him. A receiver has a wide variety of moves he can make and patterns he can run. But all of them come off his position on the field and the initial path he might take, and when you draw it all up on a board it looks like a tree. It really does. Here’s a partial map of some of the moves a wide receiver on the left side of the line might be asked to make. Bear in mind, these are “routes” he would run as fast as he can immediately after the ball is snapped by the center to the quarterback.

A “quick out” goes only five to seven yards. Same thing with a “quick in.” A “deep out” can be the same move but much deeper

down the field—fifteen or twenty yards or more. There’s a wide variety of other moves—the “come back,” the “curl-and-go,” the “in-and-out,” which combines a “slant in” with a “corner” route. If it’s an angle in geometry, football’s got a name for it and you can draw it on a board. Now each player who is eligible to run a pattern and catch a pass is assigned one of the above moves on any given passing play. Put all of the possibilities for one receiver together, and they look like this:

That’s a passing tree for just one wide receiver. In the playbook, each one of those little arrows has a number or a name. When the quarterback calls a play, like “66, yellow 40, 22Xgo,” each one of the receivers has a designated path to follow (one of the little arrows above). So as you can see, everything is done as precisely as possible. Each receiver

has his own passing tree, the quarterback calls plays based on the pattern from the tree that he wants from each receiver, and each one knows where he’s supposed to be on every play. That’s his responsibility. He must cut left or right at precise angles, all of them identified on paper and practiced over and over again in drills on the field. The quarterback, then, has to know where every one of them is supposed to be, and he has to do this with as many as five different players at once.

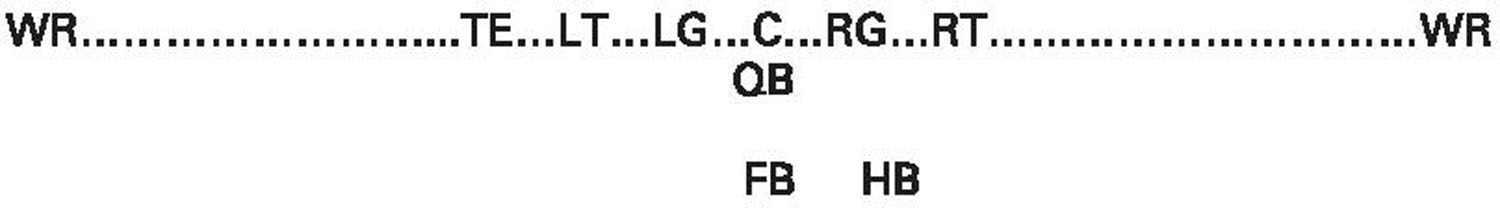

So now here’s how an offense lines up on the field:

WR = wide receiver, TE = tight end, LT = left tackle, LG = left guard, C = center, RG = right guard, RT = right tackle, FB = fullback, HB = halfback or running back, QB = quarterback

The quarterback takes the ball directly from the center in this formation. That side of the line where the tight end lines up is called the “strong side.” The tight end can be an extra blocker on running plays or a receiver who runs one of the patterns on the passing tree. The dotted line is the scrimmage line. The center lines up directly over the ball at the beginning of every play and play begins when he “hikes” (snaps) it to the quarterback. There must be seven men on this line at all times before a play—you can have more than seven, but not less. The rule says, “Eligible receivers must be on both ends of the line, and all of the players on the line between them must be ineligible receivers,” that is, they cannot catch a pass or take a hand off from the quarterback. There are a wide variety of variations on this rule, however. Some teams will use what is called a “slot receiver” and replace the fullback with another wide receiver and place him just behind the line of scrimmage but split

wide between the tackle and the wide receiver on a given side. Sometimes they’ll use four wide receivers, no tight end, and one running back; or even five wide receivers. Here’s an example of a three-wide-receiver formation. In this set, a running back is replaced with another wide receiver and he lines up in the slot, between the right tackle and the wide receiver on the right side. So on this one play, the quarterback would have this kind of set up, and expectation.