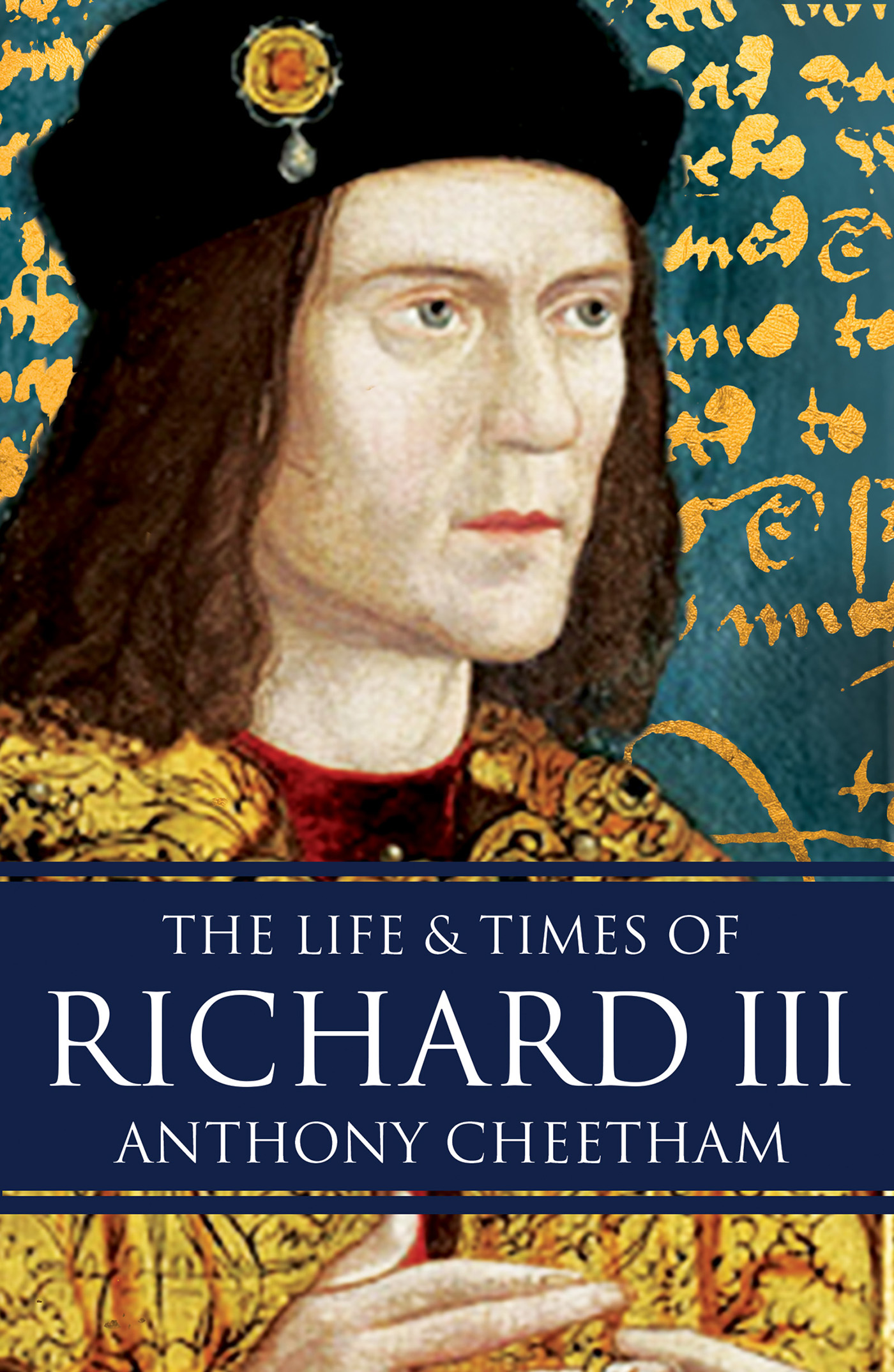

The Life and Times of Richard III

Read The Life and Times of Richard III Online

Authors: Anthony Cheetham

About

The Life and Times of Richard III

Part 1

:

York and Lancaster

1452–61

Part 3:

‘Loyalty binds me’

1471–83

Part 4:

The Usurper

April–July

1483

Part 5:

‘The Most Untrue Creature Living’

August–November

1483

About

The Life and Times of Richard III

An Invitation from the Publisher

The most controversial king in English history – his passionate admirers would still not deny this title to Richard III, while continuing to see in him the most maligned of our sovereigns. As for those nourished beyond redemption on the black legend of Crookback Dick, even they must admit that his reign contains a spectacular historical problem in the deaths of the Princes in the Tower, the exact truth about which is still not known even after a lapse of five hundred years. Of course the trouble with this type of riddle, as Anthony Cheetham ably shows in a highly readable new biography, is that although it arouses the detective instinct in us all, at the same time there is the risk of its overshadowing the whole reign – to say nothing of the true personality of the man himself.

Thus it is especially valuable to have the fact of Richard’s early life unrolled, including his own position in the complex family tree of York and Lancaster, for without this it is impossible to assess the man. It is a youth of promise, both military and administrative, including a decisive action at Tewkesbury and excellent handling of the North on his brother’s behalf, as a result of which he was termed by those in a position to know ‘our full tender especial good lord of York’. By the age of thirty he had been made Hereditary Warden of the Western Marches of Scotland by Edward as a reward for his good services to the Crown. Hard-working, brave, small in stature but still handsome (not in fact a hunchback, although one shoulder may have been slightly higher than the other), the ascetic figure of Richard presents a strong contrast to his brother the King, a golden-haired giant in youth but becoming ‘overweight and oversexed’ with age, and loaded with the problems that his indulgent marriage to Elizabeth Woodville had landed on the country in the shape of her grasping relations.

Indeed it is in this contrast that Anthony Cheetham looks for the source of Richard’s trouble with the old régime on his brother’s death; this plodding, even Puritanical, character, disliking the free and easy ways of his brother’s Court. Even the usurpation is seen in the context of the terrible disaster that the minority of a child king could bring upon a country, Richard in his short reign concentrating on much constructive work towards better government. There still remains the problem of the young Princes’ fate: here Anthony Cheetham is in no sense concerned to whitewash his subject. He contributes instead a lucid discussion of the evidence – showing incidentally how much of it derives from subsequent Tudor propaganda – at the end of which he demonstrates how, if Richard was guilty, at least it accords with the straightforward personality of the man, a man who was so far from being Shakespeare’s calculating villain, that he probably possessed if anything ‘too little guile rather than too much’.

York and Lancaster

1452–61

At the Northamptonshire castle of Fotheringhay, on 2 October 1452, Cicely, Duchess of York, gave birth to a son, who was christened Richard after his father. The Duchess was renowned for her beauty and for her enduring devotion to her husband. Known as ‘the Rose of Raby’, she had married comparatively late, in her mid-twenties, and accompanied her husband on his tours of duty in the French territories conquered by Henry V and in the Irish pale. Undaunted by the hazards of war, travel or continual pregnancy, she had already borne ten children in three different countries before the young Richard first saw the light of day. Six of these children – three boys and three girls – had survived the rigours of infancy: in 1452 Richard’s eldest brother Edward was ten years old, Edmund was nine, and George was four.

All three inherited something of their mother’s looks and robust constitution. Richard, the last of Cicely’s surviving children, seems to have inherited neither: a weak and sickly child, he struggled through his early years, causing an anonymous rhymster to comment, with a note of surprise, that ‘Richard liveth yet’. In looks and height he would later resemble his father, a shortish man with plain, forthright features.

Richard, Duke of York, was the greatest magnate and landowner in the kingdom, excepting the king himself. From his mother, Anne Mortimer, he inherited the vast Welsh border estates of the earldom of March, the earldom of Ulster and the Irish lordships of Connaught, Trim and Clare; from his father, Richard, Earl of Cambridge, the dukedom of York and the earldoms of Rutland and Cambridge. Through both his parents York also inherited the royal blood of Edward III. On the one side he traced his descent from Lionel, Duke of Clarence, second son of Edward III; on the other he was the grandson of Edward III’s fourth son, Edmund of Langley. These family relationships are of more than passing interest: their shadow lies across the short and violent span of Richard’s life, and stains the whole chapter of English history known as the Wars of the Roses.

The fortunes of the House of York were founded on the fact that their royal descent was arguably better than that of the reigning House of Lancaster. For while York could claim descent from the second son of Edward III, Henry VI could trace his only from Edward’s third son, John of Gaunt. King Henry thus owed his crown more to the successful usurpation of his grandfather, Henry Bolingbroke, than to the legitimate laws of inheritance.

These dynastic subtleties might well have remained purely academic, if the kingdom had not been wracked, in the years preceding Richard’s birth, by a series of crises that left the King bankrupt, the barons at each others’ throats and the country shorn of its empire overseas. King Henry himself was most to blame. At a time when the King was expected to be his own prime minister and commander in chief combined, Henry was interested only in charity and prayer. This saintly incompetent allowed his ministers to pillage the royal coffers to the tune of about

£

24,000 a year. Nor was he able to devise an effective policy towards the besetting problem of his dwindling possessions in France. Henry V’s great conquests had saddled his son with an embarrassing legacy – crushingly expensive to maintain, humiliating to abandon. In 1444 his advisers persuaded the King that he must cut his losses, come to terms with the French and marry a French princess. The bride chosen by Henry’s advisers was Margaret of Anjou, daughter of René, Duke of Anjou, and niece of the French King, Charles VII. Although she was only fifteen years old, Margaret’s dazzling looks, her lively intelligence and her impetuous energy soon wrought a transformation in the routine of her husband’s Court. With more gratitude than foresight she also linked her fortunes – and the King’s – with the second-rate ministers who had made her a Queen. But the French truce negotiated by her favourite protégé, William de la Pole, Earl (later Marquess and Duke) of Suffolk, lasted only two years. In 1448 the province of Maine was ceded to the French: in 1449 Normandy went the same way. By now the country was baying for the blood of the appeasers whom it held responsible for these disasters – Suffolk, Somerset and Queen Margaret.